When it comes to their country, Americans never really embrace the “caring is sharing” mantra.

The fact that xenophobia — the intense dislike of people from other countries — is now, once again, a regular feature of campaign coverage is unsurprising. Since xenophobia emerged in the late 1700s, it never really went away. But it’s time to change the rhetoric and to stop feeding into the cycle of treating these views as commonplace simply because they persist.

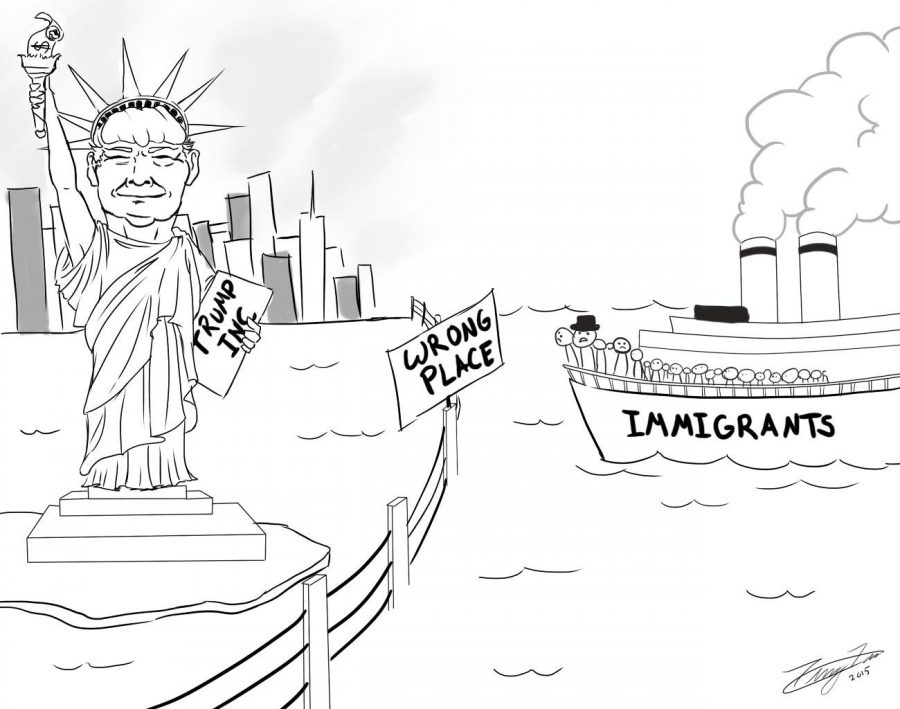

It seems like every few decades a new group to fear and blame for economic instability forms. This time, Mexican immigrants have become the focus of outrage, being labeled as tax-avoiding job thieves. These critiques are not new, only the critics espousing them are — Donald Trump serving as the most recent of these cartoonish characters. These accusations, though previously reserved for only the most conservative outlets, have increasingly entered the regular news cycle. While these sentiments may seem like a new level of extremism, their arguments persisted throughout our country’s history.

Trump has dominated the news cycle since he launched his presidential campaign in June, as has every word that he’s said since. As the candidate leading every Republican poll, those words steer the entire Republican field into anti-immigration waters.

Trump recently released a six page immigration plan in August that was simultaneously hailed as “ludicrous” by NPR writer John Burnett, and “the greatest political document since the Magna Carta” by conservative commentator Ann Coulter. The key part of his $166 billion plan is a call for the mass deportation of all 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants currently living in the United States. According to Trump, the “good ones” would be allowed back into the country if they met unspecified criteria.

Trump represents an extreme, but recently, several of his opponents have followed his lead on the issue. Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey recently suggested tracking immigrant visas like FedEx packages, and Gov. Bobby Jindal of Louisiana was quoted as saying, “Immigration without assimilation is invasion.” Christie, Jindal, Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky, Sen. Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania, Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Gov. Scott Walker of Wisconsin have all voiced support for an end to birthright citizenship, which is Trump’s most radical stance thus far.

We cannot understate the impact of the initiative. Nonpartisan polling organization Pew Research Center estimated that 7.5 percent of annual births in the United States are to unauthorized immigrants. This means that about 4.5 million people born in America would suddenly have no place to call home.

The only way to achieve this proposal involves passing a constitutional amendment to repeal the 14th Amendment, which guarantees citizenship to any person born in the United States, regardless of the parents’ legal status. This is a prospect so nuanced and controversial that many writers — such as Alan Gomez — say it is likely never to happen. Nonetheless, Trump is treating the proposal as a legitimate goal.

Why, in 2015, has the conversation on immigration turned from reform to leaving millions of people nationless? The only real way of answering this question is to look at the context of these nativist cycles because we have, unfortunately, been here before.

In 1798, President John Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which tripled the length of required residency for U.S. citizenship and streamlined deportations. At the time, America was in the midst of a trade slump as a result of the French Revolution. Worries of radical French spies grew rampant. This is a consistent theme for America — when the economy slumps, Americans often first attack groups perceived as others.

In the 1840s, Catholic churches burned across Philadelphia in response to Irish workers, who would work for lower wages after fleeing the famine of their own country. Meanwhile, waves of Chinese immigrants began to flood the west coast and found cheap work on railroads, then organizing their own communities within major cities like San Francisco. The Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882 abruptly cut this flow by banning Chinese labor immigration for an entire decade. This was the first U.S. law to officially limit immigration. Forty-two years later, the Immigration Act of 1924 banned all Arab and Asian immigrants and set a yearly limit on the total immigrants allowed into the country.

Comparitively, other countries have adopted more open immigration poliicies. For example, Canada uses a points system to solicit immigrants through its federal skilled worker program, and only 67 points out of 100 are needed to obtain an entry visa. In the U.S., immigrants are required to file for H-1B temporary visas, which are capped at 85,000 annually, and can only be filed on April 1. Spain has run the most legalization programs, having run six since 1985. The U.S. has constantly debated legalization of the millions of illegal immigrants.

[graphiq id=”36LbkH9Stb7″ title=”Unauthorized Immigrant Population by State” width=”600″ height=”481″ url=”//www.findthebest.com/w/36LbkH9Stb7″ link=”http://us-presidents.insidegov.com” link_text=”Unauthorized Immigrant Population by State | InsideGov”]

Even attacks on Mexican immigrants are nothing new. The U.S. deported nearly 1 million Mexican immigrants during the Great Depression out of fear that they were taking jobs from white Americans. This should sound familiar because it is essentially Trump’s planned policy, enacted 80 years ago.

The commonality here is an influx of low-skill workers. Unauthorized immigration from South and Central America saw a rapid increase during the 1990s and early 2000s when the number of unauthorized immigrants jumped from 3.5 million in 1990 to the 2007 peak of 12.2 million, according to the Pew Research Center. These undocumented immigrants make up 5.1 percent of our labor force. The number has stabilized over the past five years, but the spike was enough to set off this current chain of xenophobia.

The irony is that cheap labor is the foundation of the American economy. Capitalism upholds that if someone is willing to accept less money to do the same job as another person, they should take the deal. Cutting costs and reinvesting profit is the ultimate goal. So why are conservatives, the people most fiercely supportive of free markets, suddenly uncomfortable once the people taking advantage of them speak another language?

Conservatives typically counter with the argument that immigrants occupying low-wage jobs result in lower overall wages. It would then seem sensible to support reasonable minimum wages and labor regulations that prevent companies from sending jobs overseas. But establishment conservatives continually embrace pro-business policies that run counter to both of these initiatives, like providing tax breaks for outsourcing jobs and lobbying against federal regulation of minimum wages. Senate Republicans blocked a bill in 2014 that would punish companies that send jobs overseas by ending their tax breaks. Tim Worstall, a regular contributor for Forbes, wrote an opinions piece titled “The Moral Argument Against Raising the Minimum Wage.”

This contradiction results in the oppression and dehumanization of millions. It persists because people are naturally scared when money is tight. It spreads quickly because people are easy to persuade when scared. And it fades because immigration actually provides an absurd number of benefits, both economic and social.

By occupying low-skill jobs, immigrants encourage Americans to specialize in more highly skilled professions. That pushes innovation within the workforce, allowing the economy to grow in response to shifting markets. Not all immigrant workers fit this mold, however, and those that bring education and skills with them provide an inherent benefit to our overall economy.

On the most basic level, immigrants enrich our culture by sharing their own. This is something to be valued, not feared — and, according to a Gallup poll, 65 percent of Americans do see the value of immigrants, favoring a path to citizenship.

At the end of the day, we are wasting our time by vilifying some immigrants for taking low-skill jobs that we should be willing to hand off.

After all, if you listen to Scott Walker, Canada is the true concern.

Write to Matthew at [email protected].