After serving two years in prison, and later being arrested in front of her 4-month-old daughter, Sarah Womack turned to prose and poetry to stage her comeback.

“I come from alcohol. Uncle Kenny, glass shaking in his hand — yellow, gray, bloated. / I come from alcohol. I seize and hallucinate in my hospital bed,” Womack writes in one of her poems.

Womack wrote the poem at the Sojourner House — a residential rehabilitation house for mothers and their children — in 2013, through a program designed to help inmates and recovering addicts express themselves through words.

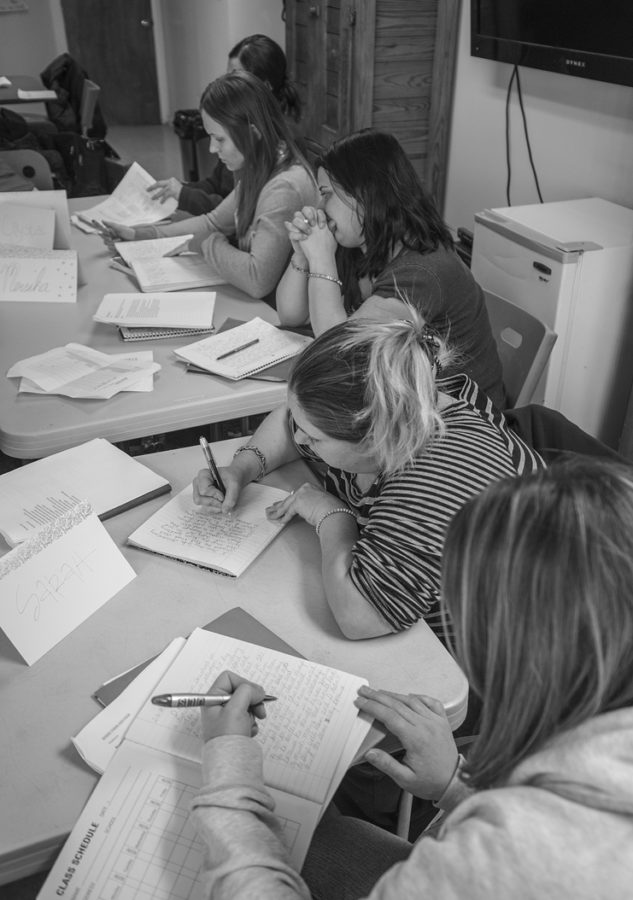

The program, called Words Without Walls, is a writing outreach program at Chatham University that has MFA students teach creative writing courses to interested students at the Allegheny County Jail Downtown, the State Correctional Institution-Pittsburgh just west of Downtown and the Sojourner House in East Liberty. Founded in 2009 by Chatham University alum Sarah Shotland and program director and professor Sheryl St. Germain, Words Without Walls teaches 18 classes every year and publishes an anthology of its students’ best work at the end of every cycle.

After teaching in a prison in Iowa, St. Germain wanted to start a similar program in Pittsburgh. The idea caught Shotland’s interest and the two spearheaded the program at Chatham.

The program aims to use creative writing to bring down pre-existing “walls” — both physical and metaphorical — that separate inmates and recovering addicts from the rest of the world. With 49,914 offenders in the system in 2015, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections has no shortage of potential students for programs such as Words Without Walls.

Pitt will soon join Chatham in working to help people find their voice. Beginning in the 2017 fall semester, Pitt will hold courses at the State Correctional Institution-Fayette through the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program — a national program that brings educators into prisons to teach classes to inmates.

Inside-Out, which began in 1997 and has spread to nearly 100 colleges and universities, differs from Words Without Walls in that the classes include an equal number of undergraduate students and incarcerated students in the same classroom — in Pitt’s case, these classes will take place inside the State Correctional Institution-Fayette building. Also unlike Words Without Walls, the Inside-Out program teaches a wider variety of classes than just creative writing — the program through Pitt, for example, will teach literature and political science classes.

Pitt political science professor Chris Bonneau, who will be teaching a course in Pitt’s Inside-Out program in the fall, heard about the program on NPR and immediately identified a need for such a program in Pittsburgh. Bonneau worked with Pitt English professor Shalini Puri to establish a chapter of the program at the University.

“Most of these individuals are going to be released at some time. And a lot of them want to improve themselves,” Bonneau said. “So if we can help them improve their situation, to give them a skill like critical thinking or writing, or help facilitate that … we have, I think, an obligation to do that. And that helps everybody.”

Pitt’s program will share many similarities with Words Without Walls, whose instructors often have to adjust on the fly to new group dynamics as well as a variety of educational backgrounds. The non-traditional students in Words Without Walls also often have a variety of interests, ranging from fairy-tale literature to U.S. citizenship. Many students, such as Womack, have backstories rooted in pain or regret, and take a chance on the writing program as a means of trying to heal.

“When you’re out there using drugs and alcohol, you don’t believe that you’re worth anything, you don’t believe that you’re good at anything anymore,” Womack said. “[Words Without Walls] gives people who don’t have a voice, a voice.”

Pitt National Scholarship Adviser Ian Riggins — who got his MFA at Chatham and is a former Words Without Walls teacher — heard about the program through word of mouth from graduate students already teaching in the program, and was immediately drawn in. He said he was excited to practice creative writing with a new demographic of students but quickly discovered just how new of a teaching style he would need.

“We created this whole syllabus and all these things we were going to focus on, but after the first day, we realized our syllabus wasn’t going to work at all,” Riggins said, referring to the erratic student attendance that comes in a prison classroom setting. “You could be locked down in your cell, for example, and not be able to get out and do something or someone might not be able to attend class because of that.”

To adapt to the new setting, Riggins begins a class session with a writing prompt, followed by a reading and group discussion and finally another writing prompt in response to the reading.

“Chatham gave us a lot of freedom to do what we wanted to do with the class and what we thought was best,” Riggins said.

The program has helped students receive national recognition and opportunities for publication of their work, pursue MFAs of their own and gain a more in-depth experience with its Maenad Fellowship program at Chatham University.

Admitted fellows, such as Womack, participate in a 12-week series of creative writing practices, weekly seminars and a final public reading fundraiser — which took place April 13, at the Irma Freeman Center for Imagination in Bloomfield.

Words Without Walls impacts not only its students, but its instructors as well.

MFA Program Assistant at Chatham and recent alumna Brittany Hailer was a first-year MFA student in 2013 when her father — a drug addict — suffered a mental breakdown on the first day of classes at Chatham. He disappeared and has since remained unknown and absent from Hailer’s life. St. Germain suggested Hailer shadow a Words Without Walls writing class.

“I came to my first day of class and was trying to pretend like I belonged, but I felt very out of place. And [St. Germain] recognized it immediately,” Hailer said.

From there, both Hailer’s public and private written lives began to stabilize.

“We were asking these women to write about their trauma and to be very confessional, and I myself wasn’t doing that,” Hailer said. “So I started to write alongside of them and it completely changed my writing.”

Hailer not only saw the liberating effect that writing was having on the women at Sojourner House, but also learned to cope with her own pain as well. As a result, her own writing has become more transparent and more focused on social justice issues.

“There’s something about the community and literature that unlocks something,” Hailer said.

But it doesn’t come easily. Students in prisons or treatment centers often have reservations at first about opening up and facing their past head on. Hailer addresses this apprehension by, for example, encouraging her students to tell their own histories through the lens of fairy tales.

After having students read a fairy tale poem, such as Anne Sexton’s “Cinderella,” Hailer asked the students to consider the evil stepmother with questions such as, “How did she become who she became?”

“And then they’re writing about themselves as the stepmother,” Hailer said. “Not only are they writing a metaphor without even realizing it, it’s also easy to write from a voice that isn’t necessarily your own.”

Hailer brings her students to a state of mind they normally don’t think about visiting and that they’ve tried to repress in an effort to block and run from their past selves or mistakes. In expressing their own honest thoughts and inner vulnerabilities — on the page and in the classroom — the teachers establish a kind of credibility among the enrolled students.

“Something that I try to do is create empathy between us. I tell them about my dad the first day, and, because I am the child of an addict, they then realize that maybe their kids could someday get a master’s degree,” Hailer said.

Sharing words and experiences is just as crucial as writing them in Words Without Walls, which is why the curriculum always entails students reading their work aloud, a part that former Words Without Walls teacher Maggie Pahos said was integral to the program’s success.

“I think aside from the writing, some students found a place to talk about some things that had been on their minds and on their hearts, that they weren’t able to talk about in other settings,” Pahos said. “For me, that’s the most important part of writing.”

Womack said, because the program emphasizes sharing and exchanging feedback, she struggled during her time at Sojourner House with reading pieces aloud about her daughter or her history with using drugs, but says it was fundamental to her healing process.

“I’ve had such an overwhelmingly good response from being honest about my experiences and writing them as honestly as I can,” Womack said. “And it’s important for me to read them publicly or to have them published because I want other women to know that they’re not the only ones who have experienced the things that I’ve experienced.”

Since completing the Words Without Walls program and now nearing the end of her Maenad Fellowship, Womack plans on submitting some of her work for publication and has already been contacted by Pittsburgh Parent Magazine to do some freelance work.

Through Words Without Walls, Womack’s past became more than just history — it became a story. But of course, Words Without Walls cannot guarantee a future for Womack. The remaining pages are left up to each individual student, as Hailer has learned from personal experience.

“You can’t make anybody make the right decision,” Hailer said. “But you can give them the tools to grow confident and talk about themselves.”