Alien She looks to riot grrrl’s past and future

October 21, 2013

In 1993, the feminist punk band Bikini Kill released its debut full-length album, Pussy Whipped. “Alien She” was the title of the second track on the album. It begins with the usual confident clamor of a punk song, then above the distorted guitar and cymbals, lead vocalist Kathleen Hanna announces the opening lines, “She is me/I am her/She is me/I am her.” The lyrics propose both a unification of disenfranchised women and also a departure from the “feminine norms” of 1990s culture.

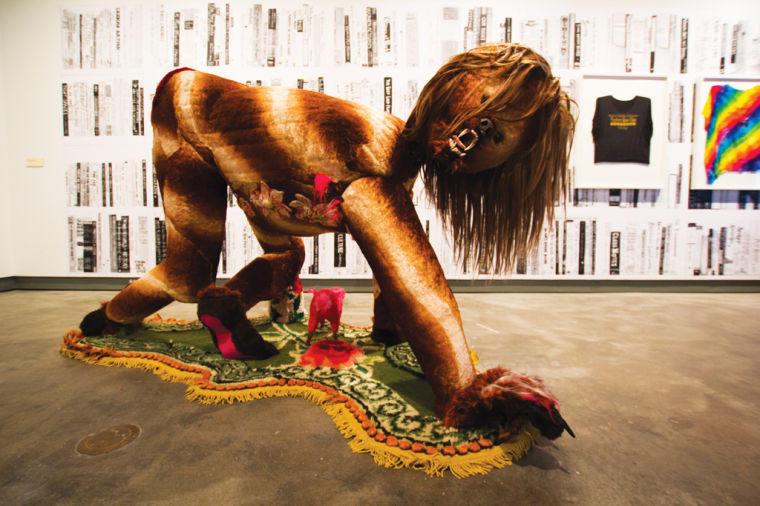

Twenty years after the release of Pussy Whipped, Carnegie Mellon’s Miller Gallery opened its new exhibition, Alien She, on Sept. 21. The exhibition presents memorabilia from the genesis of the riot grrrl era to the modern incarnations of movement chapters across the globe while also showcasing contemporary artists who have been heavily influenced by the iconic movement.

The riot grrrl movement was pioneered by bands such as Bikini Kill and Bratmobile. By incorporating the do-it-yourself punk aesthetic into music, protests, group meetings and handmade zines, young women of the ’90s could communicate and collaborate through a new channel of expression outside of mainstream media.

Astria Suparak, co-curator of the exhibition, explained why now is a good time to reflect on what the movement was and the impact it has had on modern culture: “At this point, we’ve been able to see the influence of riot grrrl in our peers, in contemporary artists and in our own careers.” Suparak stated that with the recent prevalence of riot grrrl in the world — notably the controversy surrounding Pussy Riot, an all-female band in Russia — there is no better time than now to look back on this epoch-defining feminist culture.

Ceci Moss, also co-curator of the exhibition, succinctly stated, “riot grrrl was, and still is, an expression of feminist politics … and feminism is always relevant.”

The exhibition begins on the ground floor of the gallery with a medley of archival materials dating back to the early ’90s. Hundreds of posters and flyers advertising feminist film showings and local gig concerts vie for attention on the far wall. An adjacent wall is lined with shelves of handmade zines and pamphlets dealing with issues prominent within and imperative to the riot grrrl movement, including sexism, racism and homophobia.

On the opposite side of the room, a large banner hangs alone, emblazoned with the words: “What is riot grrrl?” and the movement’s manifesto and motivations printed in bold letters, ending with the line, “we are creating the revolution. We ARE the revolution.”

A glass-topped unit encasing cassette tapes, T-shirts with hand-drawn designs and scribbled notes about songs stands in the center of the room. Visitors are invited to don headphones and listen to riot grrrl bands from America, Brazil, England, Belgium and the Netherlands. All the while, a projection of interviews with riot grrrl proponents and clips from punk shows provides both a commentary and soundtrack to the litany of materials on display. Repeated visits are necessary to digest all of these intriguing artifacts.

The second and third floors open out into a more formal affair, and this allows the works of the artists involved with the exhibition to both stand alone and function within the context of the riot grrrl retrospective. Tammy Rae Carland’s “Untitled (Lesbian Beds)” is a standout inclusion on the second floor. the piece is a collection of intimate photographs of beds baring the creases and confusion of bodily interaction from the night before, framed meticulously from above in contrast to the disorder of the unmade sheets and ruffled comforters strewn about the beds.

Carland, who collaborated on the record art for Bikini Kill albums as a part of the riot grrrl genesis in the early ’90s, is one of the seven artists involved with the Alien She exhibition to have had first-hand experience with the movement. She explained how she perceives the legacy of this era: “I think that a lot of what happened in riot grrrl just became embedded in cultural movements, both pop culture and underground movements. … What started off as a separatist movement has become an embedded movement.”

What is presented in Carland’s work is arguably a more considered and assured presentation of particular topics of sexuality and feminism when compared to the visceral, chaotic aesthetic of riot grrrl in the ’90s. She continues to suggest that “the language and vernacular of [riot grrrl] appeals to younger people.”

“That’s why it’s so important that [the exhibition] is taking place in a university,” she said

L.J. Roberts is representative of the new generation of artists to spring from the riot grrrl movement. “I was on the younger side of things with riot grrrl, but my strongest influence has been Tammy Rae Carland. She was one of my teachers,” Roberts said. Situated on the third floor of the Miller Gallery, Roberts’ work incorporates materials often equated with craftsmanship or “amateur” arts, such as knitting and banner production.

Roberts’ “We Couldn’t Get In. We Couldn’t Get Out” is a 10-foot-by-30-foot steel fence completely encased in woven pink wool. It dominates the third floor of the exhibition. Roberts explained during the opening tour of the exhibition that they used a children’s pink Barbie knitting machine to produce the piece. The boldness, intricacy and humour of their work communicates a fresh style of feminist and queer representation, informed by its punk-predecessor and also by the resurgence of craft-based production in recent years.

The third floor also hosts work by Stephanie Syjuco, whose piece “Free Text” invites gallery visitors to take a variety of tear-off tabs with URLs that supply links to free digital texts related to all manner of thematically relevant issues on gender, hacking, postmodernism and queer theory. Syjuco presents another example of an artist embracing the riot grrrl ethos and applying it to contemporary issues of digital copyrights and how, as the Internet generation, we interact with the endless amounts of information available to us.

Ginger Brooks Takahashi, a North Braddock resident, provides a retrospective of her collaborative artistic, musical and communal endeavours, all of which are presented under the striking title “A Wave of New Rage Thinking.” Takahashi plays an integral part within the exhibition. She both personifies the thriving, communal art scene in Pittsburgh and is also representative of the multi-faceted nature of riot grrrl, refusing to confine herself to one medium and one avenue of expression.

Sara Marcus, author of “Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution,” the first publication to document the history of riot grrrl, expressed her opinion as to why the movement has this resurgence and generates so much interest. She said, “It’s not just something that was ‘curious’ and ‘quaint,’ but because the question of how young women’s minds and lives are consolidated and communicated in our culture today is still relevant.”

In the epilogue of her definitive history of riot grrrl, Marcus outlines some truths that further support a need for a cultural shift: “Every day brought new offenses: Women were outnumbered six to one in most magazines’ lists of the past decade’s best musicians. Publishers Weekly came out with a list of the 10 best books of 2009, without so much as a single title by a female author. … A pop star beat up his girlfriend and his career barely missed a step.”

As with any influential, ideologically driven subculture, there is often the threat that the movement will eventually become oversaturated and just another marketable, empty symbol.

Yet Alien She captures the irrepressible legacy of riot grrrl and avoids reverting to a nostalgic reflection on better days. Instead, it uses the movement as a platform from which a new generation can explore the feminist and queer issues that were once erupting from punk gigs, scribbled upon leaflets and discussed at weekly meetings.

Marcus stated that “there are incredible opportunities today for people to make their own media and create communities.” Alien She certainly demonstrates such opportunities being taken by the artists involved with the exhibition and heralds them as models for the rest of our generation.