Maxine Bruhns may be best known as the keeper of the Cathedral’s celebrated Nationality Rooms — a post she’s held for more than 50 years.

But this Mother’s Day, she found herself reflecting on a different kind of history: her own ancestry.

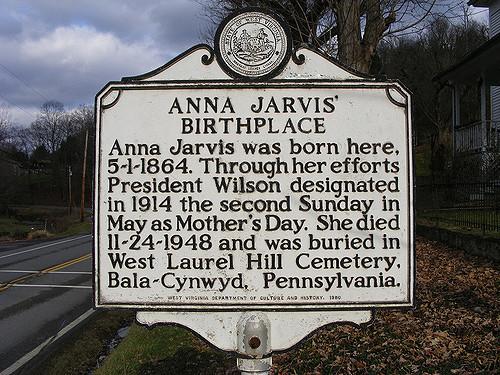

Though not a mother herself, Bruhns, the director of Pitt’s Nationality Rooms program, feels a deep connection with the annual holiday. She is distantly related to its founder, Anna Jarvis, a social activist during the Civil War.

Although the two never met, Bruhns considers herself an expert on Jarvis’ life. After hearing stories from her parents, Bruhns spent hours researching Jarvis — who grew up in Webster, West Virginia, just four miles from Bruhns’ hometown — and learning about the evolution of Mother’s Day.

Because of Jarvis’ insistence that mothers get the recognition they deserve, the Mother’s Day was celebrated for the first time in 1908 in a Methodist church. In 1914, after Jarvis formed women’s groups, penned letters to the US Government and initiated a national campaign for the cause, the U.S. declared Mother’s Day a national holiday.

Jarvis died in 1948, without any children, and after denouncing the commercialization of the holiday she’d dedicated her life to.

Bruhns sat down with The Pitt News on Monday to talk about Jarvis, the origins of Mother’s Day and why its founder eventually grew jaded about the holiday.

The Pitt News: Who was Anna Jarvis growing up?

Maxine Bruhns: The Civil War was going on and [Anna Jarvis], [her] little brother and herself and her mother and her father lived in a town outside of Webster — very remote. Her mother, Ann Reeves Jarvis…at that time she had lost 8 of her 11 children to illness. Her brother was a doctor. He taught her how to boil water and how to dress wounds antiseptically. [Reeves Jarvis] knew that a lot of children were dying because they didn’t know that and so she formed these clubs, taught the women how to do that, and sent it on. It just multiplied and the children lived more healthily. And she encouraged them that if they saw soldiers from the Civil War, north or south, it shouldn’t matter, that they should just dress their wounds and help them live.

And so she was up to that in her eyeballs and one day she was saying a prayer […] ‘God, I hope that somehow, someone will find a day that honors all the mothers of the world.’ And she said it to God but Anna never forgot… so when her mother died in 1905, she said at her gravesite, ‘God willing, mother, one day you will have this Mother’s Day.’ And so that became her resolute priority in life to make a nationwide — now it’s worldwide — Mother’s Day. So that’s the way that happened.

TPN: What’s your relationship with Jarvis?

MB: By 1907 [Jarvis] had started an aggressive campaign for Mother’s Day and my mother was a secretary at the B&O [The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad]. My dad was an engineer for the B&O. My mother was typing there and Anna Jarvis would come and give them letters to type, hundreds of letters and so she and the other women would type these letters urging people to have Mother’s Day.

My father — his great grandfather was a Jarvis, and so he was a third cousin of Anna Jarvis. So one day, my mother and dad were walking in the street near the B&O and there comes Anna Jarvis. And my mother hit him in the ribs and said ‘There’s your cousin, go tell her who you are.’ And so he did but I never heard what the conversation was about, but at least he met her. She was famous — infamous — by that time.

TPN: Do you feel connected with her even though you haven’t met her?

MB: [On Sunday] I went to the graduation at the Law School and they recognized all the mothers there, so I really feel connected through her legacy of recognizing mothers for how wonderful they are. I’m pleased — mothers were very often not recognized or praised and now everybody does something on Mother’s Day. I’m pleased to be the only living connection with Anna since she had no kids.

TPN: I heard that Jarvis eventually denounced the commercialization of Mother’s Day and tried to remove it from the calendar. Can you tell me more about that?

MB: The trouble happened then when Mother’s Day became national. [Anna’s mother’s] favorite flower was the white carnation and so [Anna] decreed that the white carnation would be the Mother’s Day flower and those who were living mothers could wear red carnations. Well that soon dissolved and the florist began making paper carnations and that really upset her. And then the cardmakers started making Mother’s Day cards and she said in public ‘The only children that would send a Mother’s day card would be those that are too lazy to make a phone call or take her to dinner.’ So she fought against this commercialization for years. She spent all of her money and it was a useless fight, they were going to sell paper carnations forever. And she actually in her 70’s went into a mental institution; it was driving her crazy. And then she died at age 84. But she is really remembered.

TPN: What is the International Mother’s Day Shrine?

MB: She made friends in Philadelphia with [John] Wanamaker [founder of one of the first department stores in the U.S.] who did all the bake shops. He liked her idea and so the very first year in 1908, she had in this little Methodist Church, a Mother’s Day where she praised her mother and all mothers. That is now known as the the very first Mother’s Day. The next year, all the churches in Philadelphia celebrated Mother’s Day. And so she kept writing those letters and finally Wanamaker introduced her to Woodrow Wilson, the president. And so by 1914, he had declared Mother’s Day a national holiday and that was really what she wanted more than anything. And so that little church, that Methodist Church where her mother had taught Sunday school and where the first Mother’s Day service was held, became the International Mother’s Day Shrine.

TPN: How has your family traditionally celebrated Mother’s Day?

MB: I lived abroad for 15 years so I could not go home. Let’s see, I lived in Austria, Viet Nam, Cambodia, Iran, Germany, Greece, Gabon, and so I didn’t have much time to visit my mother but I always phoned her on Mother’s Day and so she was pleased.

TPN: What does Mother’s Day mean to you?

MB: I always think about the woman who founded it and how pleased she would be that it’s still going on and it’s worldwide now. I mean people, everybody had a mother. And so I’m pleased to be related in some way to this woman who died unhappy, wanted it to be non-commercial. She failed, but that was bound to be.