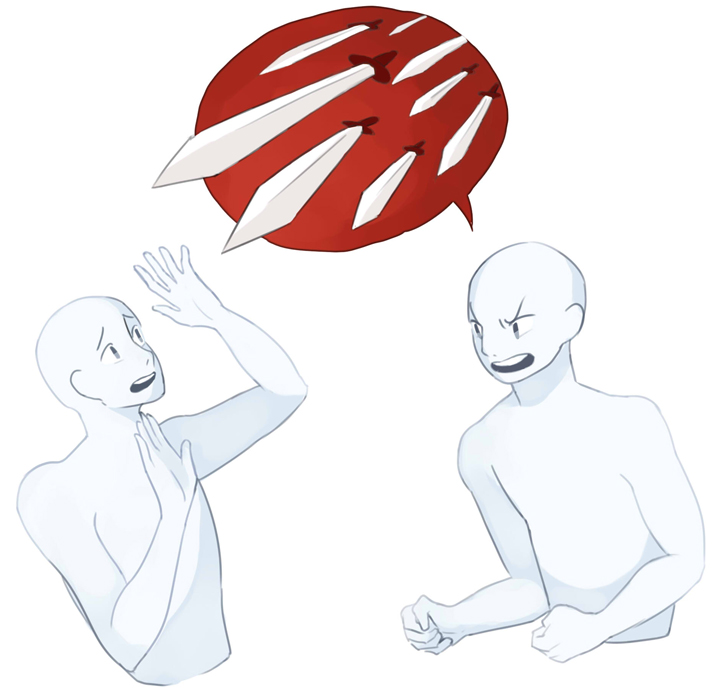

Words and swords are not the same weapon — at least they’re not supposed to be.

But the rise of politically correct, sensitive policy-making in recent years has contributed to the decline of academic freedom and intellectual discourse. In the most extreme cases, this trend has led to violent confrontations.

In their most common forms, conservatives have long argued that the rise of safe spaces and trigger warnings are inhibitive of free discussion, but the trend of violence is proving to be just as harmful.

The redefining of words and their meanings is nothing new in academia. Words like “gender” and “sexuality” are constantly shifting in meaning to the whim of students and faculty. Simple terms we all grew up with have now become abstract, dimensional constructs that vary from person to person. While gender has traditionally been a dichotomous term meant to distinguish between male and female, now it is deemed whatever an individual wants it to mean, offending anyone who questions it otherwise.

Those who question these types of nuanced meanings and symbols are simply making semantic arguments, and they don’t threaten to harm students, faculty or speakers directly. But there is one push against a particular word’s accepted definition that could be even more dangerous: violence.

Progressive activists are trying to label anything and everything as violence, whether it’s Trump’s latest remark or not using a person’s prefered pronouns. Collegiate academics continue to dilute the meaning of the word “violence” and push the narrative that lectures or speakers that make students uncomfortable are “unsafe.”

Traditionally, violence has always been the intention to hurt, damage or kill someone using physical force, not a controversial idea or opposing viewpoint.

In doing so, we are running the risk that progressives will react with exaggerated aggression toward their conservative counterparts, in some cases physically.

In August, John Ellison, dean of students at the University of Chicago, issued a public notice letting students know the school doesn’t recognize “trigger warnings” or “safe spaces.” It was a move meant to discourage political correctness and encourage healthy debate. But not every college has been so straightforward about addressing this matter.

Language that is deemed as “unsafe” or “dangerous” has come to mean anything that questions the effectiveness of Black Lives Matter, takes a nuanced look at gender politics, puts forward the idea of the existence of only two genders, supports the Washington Redskins or any slew of other topics deemed too holy and righteous to be tainted with simple debate.

When discussing free speech and violence, it is important to make clear the types of speech that are already deemed “violent” or otherwise unsafe. It’s true that certain types of speech can be considered actions in and of themselves, usually in how the words serve in involving another group of people.

This is why direct threats made to individuals or groups are illegal. They’re not illegal because of the words or ideas used, but because the threats are actively trying to intimidate and control through the use of physical harm to another person.

Calling on others to commit violent acts — such as encouraging one person to attack another or yelling “fire” in a crowded theater — or soliciting help in committing an illegal act are already considered crimes in the United States, as they go beyond the exchange of ideas to the point of being violent speech.

The laws against speech that directly call for physical violence or that could physically harm another person are almost universally seen as having a positive impact. However, there is an inherent danger in conflating physical harm and threats with simply controversial speech — speech that is legal and does not invoke physical harm. In recent years, this danger has been most present on American college campuses that treat unpopular ideas as genuine threats to student safety, whether it being denying that a culture of rape exists on a campus or questioning Islam as an ideology.

If non-aggressive speech, free of threats, is considered a form of violence on par with assault in the minds of those who protest it, then it becomes acceptable for these “victims” to react in “self-defense” — perhaps even physically. When you paint yourself as being genuinely harmed by nonviolent speech, you’ve also unfairly painted someone as an assailant, and your like-minded allies could feel justified in retaliating.

In February, Ben Shapiro, a notable conservative activist and editor-in-chief of the Daily Wire, was threatened with bodily harm on a visit to University of California, Los Angeles, where a police escort was necessary to keep him away from violent protesters. His speech was on the simple topic of sensitivity on campus, an ironic situation, given the overly emotional reaction. According to ABC7 news, the protestors blocked entrances, shouting and pushing those who were attending the event where he was speaking.

Instead of contributing anything meaningful to the public sphere, these people brought down their own side of the discussion by painting a desperate and violent picture of themselves and similarly disposed students.

Furthermore, on Oct. 15, New York University College Republicans invited conservative journalist Milo Yiannopoulos to speak on their campus in November, and the event was canceled due to security concerns and threats to the community’s well-being.

“On other campuses, his events have been accompanied by physical altercations, the need for drastically enlarged security presence, harassment of community members both at the event and beyond and credible threats involving the presence of firearms or explosives,” NYU’s Senior Vice President for Student Affairs Marc Wais wrote in an email about the event.

These are only a few of the examples where we see offense and upset of one’s beliefs or sensibilities manifested into outburst and attack, both on the part of politicians and public figures, as well as on an individual basis on college campuses. While the progressive left uses outrage culture and hostility as mechanisms to drum up supporters, they recklessly disregard the damage they’re leaving to public discourse in their wake. Not only are they harming the individual, but they are dismantling the conversation at hand to barbaric tribalism.

The left is far from the only movement with wild, aggressive people. Unwarranted violence and hatred is nearly universal in ideologies, and groups cannot be expected to answer for the sins of renegades carrying their banner. However, this particular form of escalating violence, justified as retaliation against individuals who have not harmed others, is a purely left-wing problem, and has reared its ugly head most frequently in institutions of higher learning, schools that thrive and feed off of healthy debate and discussion.

If we continue to treat simple words and ideas as active forms of violence, it will be the social justice advocates that must carry the blame for the true physical harm that will be done in “retaliation” for the violence they claim they experienced by an oppositional viewpoint.

Timothy primarily writes on free speech and media culture for The Pitt News.

Write to him at [email protected]