Kelchis Radziewicz had struggled with underlying anxiety before, but after losing a close friend to suicide just before her first year at Pitt, she realized she couldn’t cope with the grief on her own.

“It was becoming unmanageable,” said Radziewicz, a junior English literature and English writing double major. “I realized that dealing with it on my own was not working.”

Radziewicz decided her best option at Pitt was to go to the University Counseling Center — a service that roughly 10 percent of Pitt students, or about 2,800 students, use per year. She had an overall positive experience at the Center, but, like many others, dealt with long wait times. And, when she decided to seek psychiatric care this year, her counselor told her that this was no longer an option at Pitt.

“I had to go through the process of finding [an outside] psychiatrist that would accept me and my insurance. I had to wait several weeks [for an appointment], and I’m still waiting,” Radziewicz said. “It would’ve made the process a lot simpler if I’d been able to see someone through the University.”

The loss of both psychiatrists — most recently Dr. John Brooks, who left in October — is just one of several changes that have taken place since Radziewicz’s first visit to the Counseling Center in the fall of 2014.

After years of long wait times — a problem that’s affected counseling centers at schools across the country — the departure of both psychiatrists and the second installment of Pitt’s mental health week, the Counseling Center instituted new policies in the summer of 2016, most of which went into effect this fall.

Students are now permitted a maximum of eight counseling sessions per academic year as opposed to the previously unlimited sessions — although group sessions remain unlimited. This is based on Pitt’s data that shows students utilize an average of four sessions per academic year. Despite the individual counseling session limit, students can now schedule a session once per week, while the previous policy allowed sessions only once every two weeks.

Additionally, four counselors are now available to respond immediately to students who walk-in or call by phone. The Center has also quickened its initial assessment process, transitioning from scheduled appointments to immediate screenings.

The changes are designed to make the Center more accessible to a larger number of students, according to Ed Michaels, who was hired last year as the Center’s director. Michaels decided on many of the changes in conjunction with Vice Provost and Dean of Students Kenyon Bonner.

But due to the University’s failure to hire a new psychiatrist and a lack of available information on updates to treatment, some students are wary that the Center isn’t changing for the better.

“I don’t think, in any way, that anyone at the Counseling Center or anyone in [the] administration is doing anything out of bad intent, and I think that they’re working with what they can,” said junior psychology and gender, sexuality and women’s studies double major Anna Shaw. “But we also have to be critical of what is happening and try to do our best.”

More counselors, no psychiatrists

Before leaving Pitt, Brooks prescribed junior Tallon Kennedy four refills on their medication that would last the until the end of December.

This means Kennedy now has one refill left.

The English literature, English writing and Gender Studies and Women’s Studies triple major has had difficulty finding an affordable option outside of the University to continue their prescription.

Marian Vanek, director of Student Health Service, said all students receiving medications have made or can make plans with Student Health Service and the Counseling Center to ensure they have access to their prescriptions through appointments with medical doctors in Student Health or providers in the community.

The University has not officially hired a new psychiatrist yet but has been looking for a replacement since the first departure of a Counseling Center psychiatrist –– Dr. Patricia Passeltiner –– in May. Recently, Vanek said there are at least two potential candidates who are “showing some interest to join Student Health, at least for a limited basis.”

But the lapse in hiring has shocked both students and other mental health professionals. Kenneth Thompson, a psychiatrist in Pittsburgh and the former president of the Pittsburgh Psychiatric Society, said he is astonished the University has been unable to hire a new psychiatrist in six months.

“Often psychiatrists like being in places where they’re at the cutting edge of scientific research in their field,” Thompson said. “It’s quite striking that the University of Pittsburgh — which has a very, very, very famous department of psychiatry in it — is unable to find psychiatrists. It’s the last thing you’d expect.”

Michaels said the University is working with both the department of psychiatry and UPMC, as well as the Allegheny Health Network, in its recruitment efforts. According to Vanek, though, the University has had difficulty finding a replacement in part because the salary it can offer is lower than what the psychiatrists could find in different settings. The salary Pitt is offering is to be determined, according to PittSource.

“It’s the same challenge that I face when I’m hiring one of my physicians,” Vanek said about the University’s budget restrictions. “We cannot offer the same salary structure that exists in private practice or in a hospital setting.”

In Pennsylvania, the average yearly salary for a psychiatrist is $178,440, according to data collected by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2015. In contrast, the national average was about $15,000 higher at $193,680 a year.

Kennedy, whose insurance doesn’t cover their medication and who is unsure of whether insurance would cover psychiatric services in the community, said their family doesn’t have a lot of disposable income, which makes future treatment uncertain.

“For me to possibly be taken off of that medication in about a month here is pretty scary,” Kennedy said.

How did we get here?

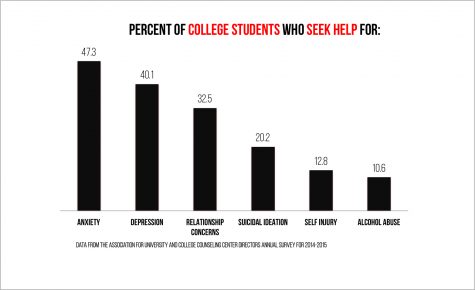

In some ways, the issues at Pitt’s Counseling Center follow trends in mental health care seen at universities across the country. In a 2014-2015 Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors Annual Survey, which Pitt took part in, 11 percent of directors reported losing professional clinical or psychiatric staff members over the course of the year.

The demand for services at Pitt’s Counseling Center has doubled this fall compared to last, according to its website. The average demand for counseling center services at 93 colleges in the United States grew five times faster than enrollment at those institutions, according to a 2015 study from the Center for Collegiate Mental Health at Penn State University.

The rising number of students using mental health services has complicated the role of college counseling centers.

When Michaels came to Pitt’s Counseling Center last June, he prepared to meet this dilemma. He started a Mental Health Task Force made up of students and professionals and benchmarked Pitt’s programs against 12 other schools, including Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania.

But complaints from students have persisted, and the high percentage of students seeking treatment is only part of the reason for long wait times and backups in care. Michaels said some students have sought long-term, repeated care when the Center is only intended to provide short-term solutions.

“There are things that we do not do. For example, we do not provide long-term treatment for chronic mental illness,” Michaels said. “If someone needs to be seen for a long period of time, they are connected to appropriate providers in the community.”

The Counseling Center’s services had previously been dominated by a smaller number of individuals who had regular appointments, filling up the staff’s schedule and creating longer wait times for new patients, Michaels said. With the new session limit, Michaels said a larger pool of students should have access to services.

Almost 50 percent of colleges in the AUCCCD survey have also instituted a session limit.

“We decided … that it was basically clinically irresponsible to turn away so many students and instead have a small handful get an awful lot [of care], where many, many more get nothing,” Michaels said.

Communication breakdown

According to Michaels, the policy changes, including session limits and an increased number of available appointments, have had an impact.

The average wait time for the month of September was four business days and the wait time in the month of October — the Center’s busiest month — was 4.5 business days. Shawn Ahearn, a University spokesperson, said the average wait time last year was about double that.

But no one would know about this impact, or changes in policy, without pushing from the Pitt community. Even as it has made changes, the Counseling Center has stumbled in maintaining transparency about its policy changes and its psychiatrist search.

Shaw drew attention to problems she saw in Pitt’s mental health services when she created an online petition in mid-October that garnered 591 signatures by Nov. 27.

Shaw didn’t talk with the Center to verify information before posting the petition. And after it triggered a flood of comments from parents, students and outsiders on social media, Pitt responded by noting that the petition inaccurately claimed that Brooks was leaving a week earlier than he was and that students would have no access to medication. Pitt posted the policies on its website after the petition, but the afterthought hasn’t been enough for many.

Max Kneis, a junior Student Government Board member, said students believe the Center still has the same problems it once had — such as long wait times — because they haven’t heard otherwise.

“I think a lot of people still say, ‘Oh, you have to wait three weeks to get an appointment.’ Well, if you hear that, you’re not going to try to make an appointment,” Kneis said. “That may no longer be true, but it was true two years ago, and the Counseling Center has not done a good enough job of telling people that that’s not true [anymore].”

Despite the inaccuracies, Shaw said she stands by the original message of her petition.

“I’m sure everyone would like to believe that every single student was able to find a place that worked for them, to not be on a long wait list, to accept their insurance, to be able to pay out of pocket, to be able to have the transportation, to have all of the factors that go into having psychiatric services,” Shaw said. “It’s just not the case.”

So what is Pitt doing now?

Kennedy was assigned a case manager — one of two hired by Michaels this summer to connect students with care— after Brooks announced he was leaving, but was said the meeting was “wholly unproductive” because the case manager only relayed the options: to look for a psychiatrist in the area or check with their family care physician.

Pitt is weighing its options in the hiring process and is aiming to hire the equivalent of one full-time and one part-time psychiatrist. In the meantime, Michaels said that the University will shortly have one part-time psychiatrist working one day per week. This psychiatrist will meet the needs of about 60 students per month.

In an interview on Oct. 27, Pitt said it had not yet hired a part-time or full-time psychiatrist. In an email on Nov. 16, Ahearn refused to answer any additional follow-up questions, including those related to the process of hiring new psychiatrists.

More than half of the colleges surveyed in the annual directors’ survey offer psychiatric care in some form, but whether that’s their responsibility is debatable.

“It’s a tricky situation, because you have to decide to what extent the University has a responsibility to its students’ mental health. And I think that it is to a large extent,” Shaw said. “It would be a different situation if [Pitt wasn’t] very vocal and very proud and kind of really out there about their services … If they didn’t say that, I wouldn’t be as disappointed or scared.”

According to Michaels, students may receive some additional counseling sessions with the input of a clinician and with Michaels’ ultimate approval.

Jake Sternberg, a senior marketing major, first visited the Center in the fall of 2015. During his first visit, the Center told him that his mental health needs — which included treatment for depression and anxiety — would be best met by a mental health professional in the community, outside of Pitt.

“As soon as I walked in, they pretty much told me, ‘Your problems are too much for what we can supply you with,’” Sternberg said. “I wish they kind of set things in a way that was more like, ‘We’re going to help you as long as we can. We’re going to help you every step along the way.’”

Michaels said the Center attempts to check in with a student referred to outside care within a week of the referral.

Apart from psychiatrists, six additional counselors have been hired at the Center since July. The Center is also hoping to hire four more counselors “as soon as possible,” according to Michaels.

To accommodate for the increasing staff, the Center is expanding its physical size by leasing space in the Medical Arts Building, at 3708 Fifth Ave., where renovations are underway. Michaels said he expects to take occupancy of the expanded space in January, although the Center’s main location will remain in Nordenberg Hall.

Ultimately, with the University’s multitude of mental health campaigns, many students see the Counseling Center as a vital component of these efforts.

Radziewicz recognizes the strength of on-campus mental health advocacy groups like Talk About It and Active Minds, but said their messages need to be reinforced by University services.

“We can talk all day long about raising awareness for mental illnesses,” Radziewicz said. “But, if we don’t have actual treatment for those students, then all of those campaigns are pretty empty.”