Column: Poetry now: why today’s world makes poetics shine

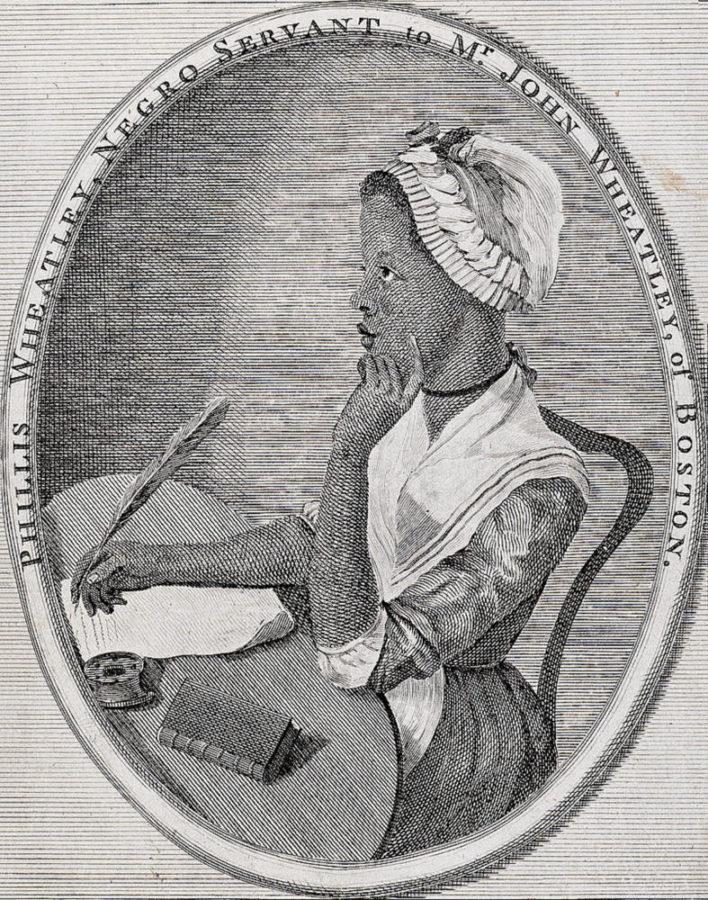

In 1773, Phillis Wheatley became the first African-American poet ever to be published. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

August 29, 2017

I remember the first time a line of poetry caught me by surprise. I was sitting in the Cathedral of Learning mouthing the words of Ross Gay’s poem “catalog of unabashed gratitude” to myself.

The poem turns when he addresses the reader, and says thank you, “for moving your lips just so as I speak.” It made me smile, and chuckle at myself for being caught doing exactly what the poet wanted.

Later I was caught again, crying as he reflected about a black friend who was murdered out of hate in whitewashed Indiana. Good poems do this — they catch you. Their lines weave into your thoughts, and you begin to find comfort in knowing that within those lines is a meaning — some kind of higher truth that will surface when the time is right.

The time is right in 2017. This year has been difficult and hate-filled, and oftentimes we have struggled to find hope. As a direct result of our increasingly distraught political and social environments, people have turned to poetics — a broad, mixed-genre term used to describe aesthetic beauty with a purpose — to find strength, community, truths and comfort. And poetics has always been this force in times of struggle.

I recently read June Jordan’s essay “The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America.” Jordan was an African-American writer who, until her death in 2002, was a prolific poet, essayist and activist. In the essay, Jordan repeatedly asks the question, “Was it a nice day?” when 7-year-old Phillis was sold as a slave to the wealthy Wheatley family in Boston, 1761.

And twelve years later, Phillis Wheatley became the first African-American poet to ever be published. In a poem that concludes the essay, Jordan writes to Phillis and says, “From Africa singing of justice and grace, / Your early verse sweetens the fame of our Race.”

How was it that Phillis, captured from her home at 7 years old and then shipped and sold across the Atlantic Ocean, was able to write verses singing of justice and grace?

One answer to this question lies in the seemingly unrelated analogy of the history of the steelpan — or as we call it now, the steel drum.

When French planters and their slaves arrived in Trinidad and Tobago, they brought with them the tradition of celebrating Carnival — a Catholic celebration period before Lent when people throw huge parties, wear masks and costumes and consume in excess what’s prohibited during Lent, like alcohol and meat. Slaves at the time were prohibited from celebrating the Catholic holiday, however, so they developed their own harvest celebration, and called it canboulay.

In 1880, canboulay turned violent. And as a result, the French colonial government banned drumming and canboulay music, fearing that they posed a serious threat to the public order. But the ban of African drums could not stop the oppressed in Trinidad and Tobago from expressing their cultural emotion through music — slaves began creating instruments from whatever they could find.

First, they used bamboo sticks. When the bamboo sticks were outlawed, they used tin trash cans. When the trash cans were banned, they used the bottoms of oil barrels. Soon, the musicians discovered something.

By beating on the same piece of metal long enough — by playing the music of their homeland on the same instrument for long enough — the tone of the steel would change. And throughout the 1940s and ‘50s, innovators experimented with intentional tonal changes and pitch layouts. Gradually, the steel drum was born.

But the steel drum would not have manifested as part of the sonic and poetic makeup of traditional culture in Trinidad and Tobago if not for the French oppressive elite continually outlawing their slaves’ instruments. And it would not be so beautiful if it were not the result of continual subversion against problematic forces.

From the loci of conflict, struggle and hate, poetics manifests.

Which is why today, American poetics are resurging into the public eye. Major publications like The New York Times and The Guardian offer suggestions of poets and poems to read, and a separate article in The Times reports that poets’ response across the country to last year’s increasing turmoil is unprecedented in terms of its quantity, intensity and stylistic and thematic diversity.

The world seems embroiled in violence, sadness and hate — that much I needn’t prove. But this means today, yesterday and tomorrow are the perfect days to read poems.

Particularly, to read poems by authors of color, by female authors, by female authors of color, by repressed authors, by jailed writers, by gender-nonconforming authors, by white authors — everyone will respond to everything differently. We can find poetics in music — be it rock or hip-hop, jazz or blues. Poetics comes from graffiti, cinema, literature or anything imaginable — which is why it is one of few tools able to respond to hatred with peaceful anger, or with unforgiving grace.

And should you feel inspired to create some kind of poetics in whatever medium you find comfortable, you might just be surprised at how calming the force of every poet — not just those who work in words — working together can be.

Christian is the assistant opinions editor at The Pitt News. You can reach Christian at [email protected].