Growing up was difficult enough with two living parents — I can’t imagine reaching adulthood with only one of them. What’s truly unimaginable, though, is growing up with your parent’s consciousness trapped inside a stuffed monkey.

If this sounds like something out of a sci-fi movie, you’re close — it’s one of the many pieces of disturbing technology depicted in the Netflix anthology show “Black Mirror.”

Season four, released Dec. 29, breaks the mold of the previous “Black Mirror” seasons, featuring a “Star Trek” satire, a black-and-white episode with little dialogue and a love story, which acts as a small reprieve from the show’s usual nihilism. The season culminates with “Black Museum,” an episode composed of several vignettes a crime museum proprietor, Rolo Haynes, illustrates to a passing traveler named Nish.

Though the show typically deals with technology gone wrong, this episode shines a harsh light on the reality of an even harsher criminal justice system. It exposes how racially charged notions of crime lead us to to impose grim — though seemingly justified — penalties.

It also comments on neoliberal ideology, showing the devastating effects of placing individual gain over the well-being of others. If there’s any apt criticism of “Black Museum,” it’s that its social commentary doesn’t go far enough to reveal the episode’s alarming parallels to American crime and politics.

Haynes begins the first vignette by revealing his previous employment — a hospital that gives treatment to those who can’t afford it in exchange for participation in experimental medical trials. “The perfect mix of business and health care,” Haynes said of the job.

This vignette tells the story of Peter Dawson, a struggling doctor Haynes convinces to test an implant that will allow the doctor to feel his patients’ physical sensations. The experiment begins as a resounding success, but before long, the implant goes haywire.

Haynes was happy to coerce Dawson into being a test subject in his vulnerable state, but once the implant begins causing problems, Haynes offers no sympathy — touting profits over people.

Even though it’s only a TV show, I’d encourage you to think again if this notion doesn’t alarm you — because it’s alarmingly resonant of the United States today.

The cost of a tax bill signed into law Dec. 22, which cut corporate tax rates from 35 percent to 20 percent, will likely fall on middle-class taxpayers of the future. It will also probably require cuts to social security, Medicare, Medicaid and children’s health insurance — even though American corporations are making record profits. Making children, the disabled and the elderly pay for the rich’s tax cuts seems typical for a “Black Mirror” episode, but terrifying in real life.

In his second vignette, Haynes tells the story of Carrie, a women who is comatose after being hit by a vehicle. The story involves her consciousness being transferred first into her husband’s brain, and then into a stuffed monkey.

Haynes tells us with a scoff that it is now illegal to transfer human consciousness into limited formats. It is also illegal to delete consciousness — so Carrie finds herself trapped for eternity inside a stuffed monkey.

While this technology may seem implausible, the sentiment that Haynes offers is all too familiar. To Haynes, a consciousness that doesn’t occupy a human body doesn’t deserve human rights. It is not a human — it is an “other.”

This is reminiscent of the way many people think of non-white people in America. Mark Steyn, a Canadian political commentator, recently appeared on the Fox News show “Tucker Carlson Tonight” and said the growth of children born in Arizona of Hispanic heritage “means, in effect, the border has moved north.”

The way Steyn dismisses these individuals as not American is eerily reminiscent of Haynes’ dismissal of human rights for human consciousnesses.

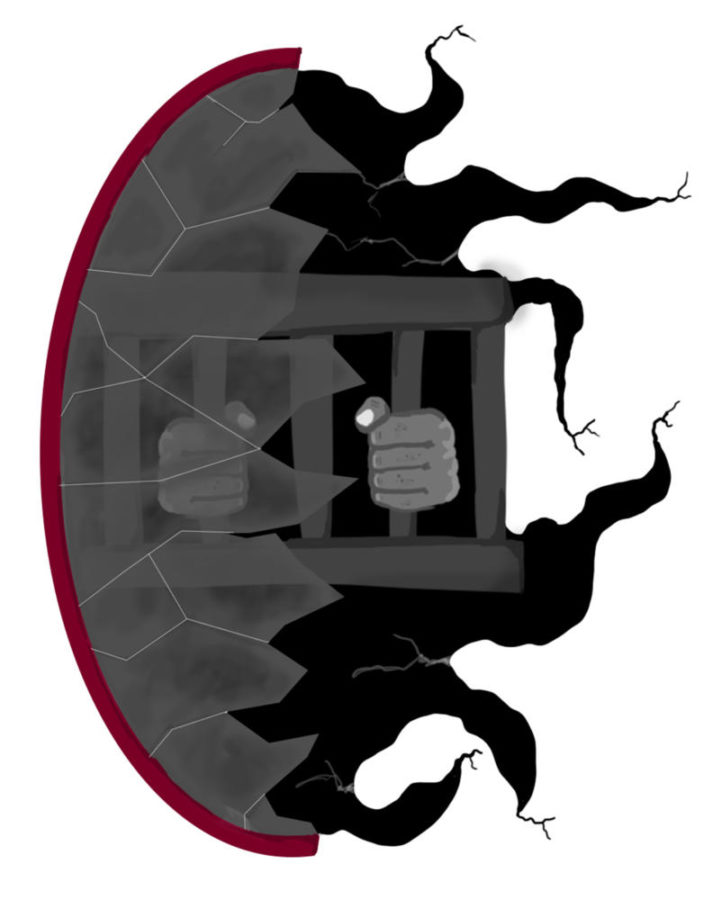

Haynes takes this disturbing rationale one step further in his final vignette. He tells us about how he convinces death-row inmate Clayton Leigh to sign over the rights to his posthumous consciousness to Haynes. Haynes uses this consciousness to create an electric chair simulation, where museum visitors can deliver electrocution to Leigh’s consciousness whenever they want, leaving him in eternal agony. Of course, Haynes justifies it by saying Leigh is a convicted murderer and is therefore deserving of eternal suffering.

The parallel we can draw between this absurd episode and the United States’ handling of crime and mass incarceration is chilling. In America, the incarceration rate of African-Americans for drug charges is more than five times that of white Americans, although they use drugs at similar rates.

And as a result, there’s been a 222 percent increase in the incarceration rate from 1980 to 2010 due to sending more people to prison for drug offenses and mandatory sentencing laws that have increased sentence lengths dramatically.

It’s justified by “tough-on-crime” rhetoric, which is particularly effective when we don’t know or care about the people we’re putting behind bars. According to a study by the Prison Policy Initiative, people who live in low-income, non-white neighborhoods are the target of these policies, as they lack the political and legal power to fight back. When this takes places far away from white, middle-class Americans, it’s easy for them to remain in the dark.

Haynes puts a human face on this inhumanity. He profits off of pure human suffering, justified by a thinly veiled criminal label. Though a mere dramatized display on television, it’s eerily similar to the private prison industry in the United States, which sees ever-growing profits as more people are imprisoned.

We are the lucky ones — able to turn off the television at the end of an episode of “Black Mirror” and escape the dystopian insanity permeating the show’s atmosphere and go back to our normal lives. But next time you reach for the remote or click “next episode” on Netflix, look closely and ask yourself if this is really that much of a departure from the real world.

Will primarily writes about politics and sports for The Pitt News. Write to Will at [email protected]