An episode of a TV tabloid talk show changed Cynthia Bradley-King’s life forever.

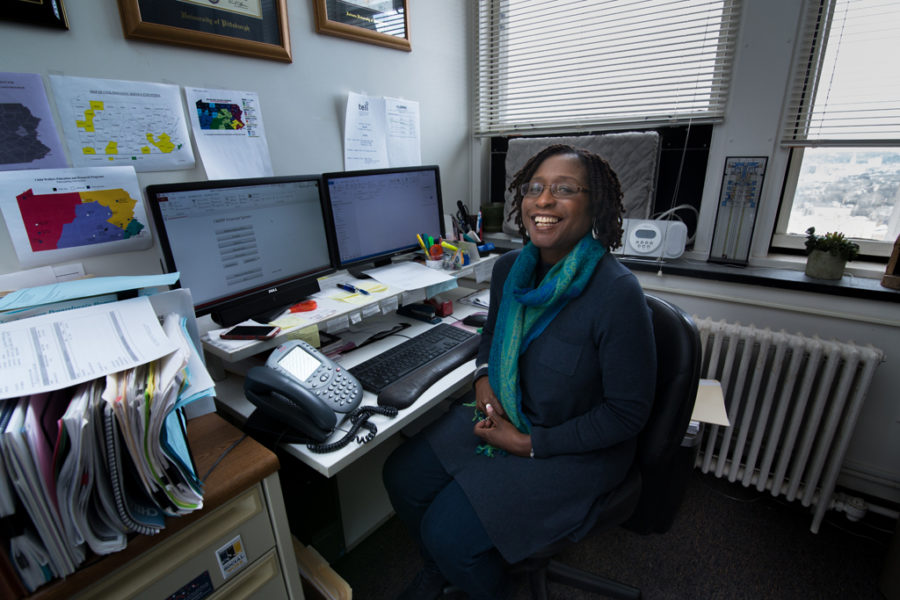

King, a professor in the University of Pittsburgh School of Social Work, runs Pitt’s Child Welfare Education for Baccalaureates program, which places social work students in fieldwork throughout the state.

Nearly 20 years ago, when King was working as a nurse, she was sitting at home watching an episode of “The Phil Donahue Show” before a night shift. She was 45, divorced and, with a son away at college, looking for something to do with her newfound empty-nester status.

The guest on that day’s “Donahue” was Matilda Cuomo, then the first lady of New York. Cuomo was speaking about the foster care system in the United States and the overabundance of children in need of loving homes. King, who is African-American, said, “It intrigued me that there were so many children up on the stage who looked like me.”

Right then, she resolved to take in a foster child.

She called the 800 number on her screen and was transferred to Family Services of Western Pennsylvania. King offered to take in a child with special needs, given her nursing background.

Within weeks, she was a foster parent to an 18-month-old girl who breathed through a tracheostomy tube. “We fell in love with her,” King said. King’s mother, who had recently been widowed, watched the baby while her daughter continued to work the night shift at the hospital, providing King with what she described as “a new lease on life.”

Six months later, Allegheny County Children Services called King back and asked if she would be willing to also foster a 6-month-old girl. King, who admits she was “addicted to babies” at this point, happily agreed. In the meantime she got remarried and, a year later, began fostering a third child and then a fourth, a baby boy who was only days old when King first met him.

“Little by little, we were able to adopt each of them,” King said. As she went through the adoption process with each of her children, King realized she wanted to learn more about the how the institution operated — how and why parents lost custody of their children. She went back to school at Chatham University to study human services administration, eventually matriculating at Pitt to earn a masters in social work.

She began working in the field and completing a doctorate in administration and leadership of human services at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania — driving 62 miles three times a week to earn her Ph.D.

King said much of her experience as a nurse carried over to social work.

“They’re both helping professions,” she said. “They are the helping professions, closely linked with education as well.”

Through social work, King studied racial inequities in the child welfare system, reflecting her initial observation of the disproportionate number of African-American children in the foster care system.

Since writing her dissertation, “The Adoption and Safe Families Act: Judicial and Child Welfare Administrators’ Perceptions of the Impact on African-American Families,” King said there has been significant reform of the child welfare system.

“The process for mandating abuse is now much more stringent, as are the consequences for not reporting,” she said.

In the last five years, more than 100 new child welfare laws have been implemented in Pennsylvania, largely as a result of the Jerry Sandusky scandal at Penn State University.

“Those children fell through the cracks. The extent of child abuse in this country is much larger than we expected,” King said. “Things that go on in the family have been thought of as private, the government getting involved in child protection is very new.”

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, the first piece of legislation to address child abuse, wasn’t signed until 1974. Since then, King said there have been tremendous advances in our understanding of the signs of abuse, as well as child development and child-rearing techniques.

“We continue to be growing as people in our understanding of children as people and how we should treat them,” King said.

She points out that she wasn’t legally protected under the law for much of her childhood in the ’50s and ’60s, as children had no defined legal rights prior to CAPTA. Understanding child welfare is a relatively new academic field, and systemic changes come only through a growth in knowledge of children.

Since becoming involved in social work, King has witnessed that growth. She cites schools and homes declining corporal punishment as an example.

In many ways, King’s parenting style evolved alongside these developments.

“I was 19 when I had my oldest son,” she said. “You think you know a lot as a teenager, but you don’t. You haven’t lived long enough.”

King took a different approach to raising her four adopted children, she said, after having the benefit of decades more of life experience, as well as a college education and one very special episode of “Donahue.”

“Anything can happen that can impact what you’re going to do for your life’s work,” King said, “and it doesn’t just have to be what you set out to do.”