Quality over quantity: Craft beer and production quotas

April 9, 2015

If you’re in The Original Hot Dog Shop on the corner of Forbes Avenue and Bouquet Street on a Friday night looking to buy beer, you’re probably not there to buy a case of Budweiser. You’re there for craft beer. You’re there because the all-American, old-school hot dog and fries shop focuses on its vast selection of hundreds of crafts and microbrews rather than Miller or Bud Light. Surely, this trend must be a sign of the times.

The craft beer I love is a novelty for its high quality. It contains grade-A ingredients. It’s made with integrity. It supports the local economy. All of this is true, but, personally, I think the best part is even simpler: It tastes better.

Craft beer is rapidly growing in popularity, and, to reflect that demand, laws are changing that allow small breweries to produce more product and call it “craft beer,” thus changing its very essence. Government regulation should not sacrifice quality for quantity.

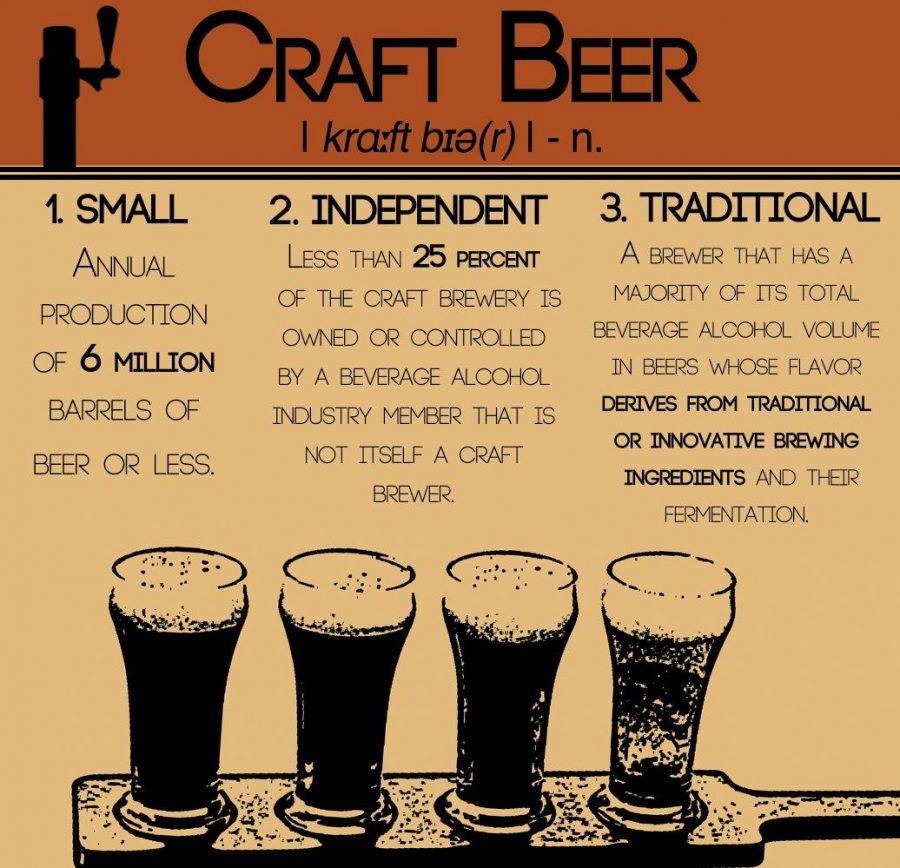

The Brewers Association, an organization operated by brewers for brewers in an effort to “promote and protect small and independent American brewers,” determined what qualifies a beverage to be called a craft beer. The Brewers Association considers a brew craft beer if the brewery produces traditionally crafted beer in small batches and if the plant is independently owned and operated.

And, if there’s one thing millennials love more than their smartphones, it’s trendy beer. A stunning 44 percent of millennials aged 21 to 27 have reportedly never tried Budweiser, which was America’s best-selling beer just a few decades ago. In 2014, craft breweries held 11 percent volume share of the market.

I find that statistic a little hard to believe, although not impossible. Beer trends reflect social trends, and our generation is conscious of pertinent issues such as sustainability, local economy and ecological footprints. We just like great-tasting beer, too.

Just look at the numbers. In 2012, craft breweries produced 13.2 million barrels of beer. In 2014, that number climbed to 22.2 million barrels.

“With the total beer market up only 0.5 percent in 2014, craft brewers are key in keeping the overall industry innovative and growing,” Bart Watson, chief economist of the Brewers Association, told The Pitt News. “This steady growth shows that craft brewing is part of a profound shift in American beer culture — a shift that will help craft brewers achieve their ambitious goal of 20 percent market share by 2020,” according to Watson.

There’s probably a market for craft beer to expand its portion of beer market share. College students love these finely crafted brews. “I love craft beer, because every time you open a different bottle, it’s like a new experience,” says Kevin Lebo, a senior emergency medicine major.

His favorite? Breckenridge Oatmeal Stout, brewed in Colorado.

But the demand in popularity is so large that the rules are changing.

Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey recently signed into motion a law that raises the production qualifications to sell on-site from 1.2 million barrels to 6.2 million barrels annually. This means that breweries can increase production to look more like that of large, corporate breweries but still market themselves as craft — small, independent, traditional.

In February, Wyoming lawmakers passed legislation allowing microbreweries to expand production from 15,000 barrels to 50,000 barrels and to continue selling on-site. Montana, Texas and Florida — among other states — have signed similar laws slowly moving away from the core mission of craft beer. Craft beer, at its crux, is an art form. Brewers invest time and dedication into the small batches of brew. When craft breweries are forced to increase the size of their operations, we lose the personal element of the beer — it’s no longer a novelty but a standardized drink.

In Pennsylvania, we have 108 breweries, one of the highest numbers nationwide. There is no law surrounding microbrewery production limits, only a minimum production floor. Brewers who produce more than 250 barrels annually can qualify for a manufacturer’s license.

Yuengling, a Pennsylvania-based brewery, recently surpassed Samuel Adams as America’s top craft brewery, according to the Brewers Association. Yuengling is the oldest brewery in the United States, originating in Pottsville, Pa., in 1829. It’s odd that Yuengling, a popular beer, is considered craft. This is a result of the Brewers Association lifting a requirement that craft beer use barley malt. This allows breweries that make up to 6 million barrels per year and consider themselves “small.” With these new regulations, who’s to say what brews are really hand-crafted after all?

So maybe that “local craft beer” you’re drinking isn’t so craft.

If the quantity is changing to meet demand and sometimes a limit doesn’t exist at all, what does that mean for quality? Increased production makes it harder to preserve the level of attention required to produce high-quality, great-tasting craft beer.

We love craft beer for its small, unique and distinct taste. At its core, craft beer aims to correct the missteps of large, corporate beer companies that care more for profit than for product. Slowly relaxing laws removes craft beer’s integrity.

If larger “microbreweries” are getting their way with legislation and the distinction between craft and commercial is weakening, then perhaps we should support our local breweries that are still committed to the product rather than the profit.

Katie McGrath primarily writes about social issues for The Pitt News.

Write to Katie at [email protected].