As the Democratic Party moves left, can Sanders still stand out?

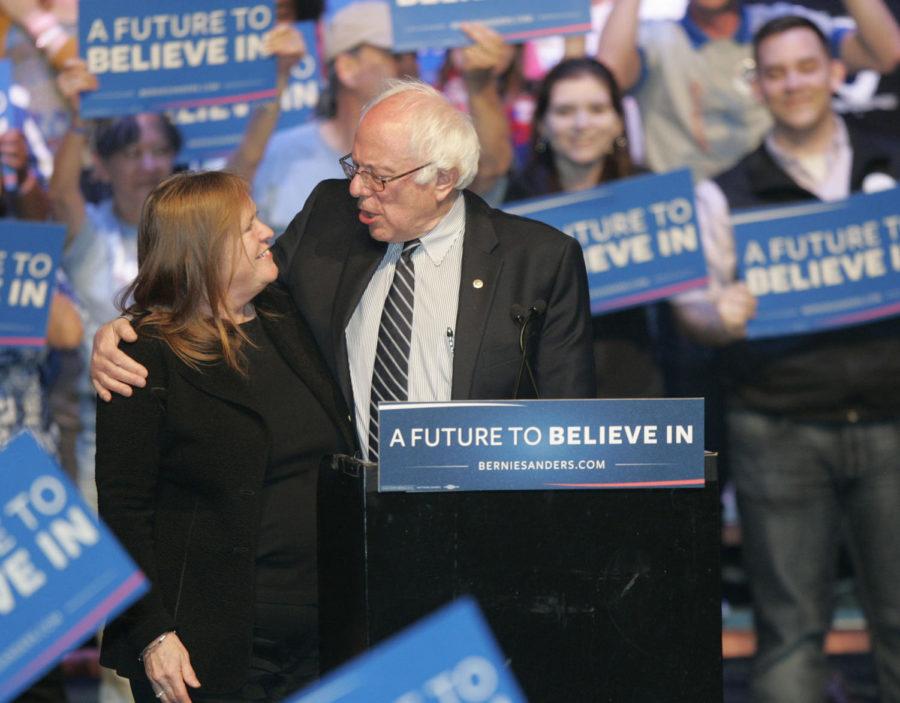

Sanders married his wife, Jane O’Meara, in 1988 and helped raise her three children from her first marriage, Heather, Carina and Dave. Sanders was previously married to Deborah Shiling Messing from 1964-66 and together they moved to Vermont. He also had a son, Levi Sanders, in 1969 with his then-girlfriend Susan Campbell Mott. He has seven grandchildren, including Levi and his wife’s three children who were adopted from China. (Bob Booth/Fort Worth Star-Telegram/TNS)

February 27, 2019

WASHINGTON — Bernie Sanders’ boundary-pushing policy agenda defined the septuagenarian senator as a fresh, revolutionary candidate to legions of young and progressive supporters, helping carry him to unexpected success in his first try for the presidency.

He won’t have it as easy the second time around.

As Sanders begins a new presidential campaign, he faces the possibility of falling victim to his own success. The policies that once made him a fringe figure in Democratic politics have — in part because of his own popularity — been widely adopted inside the party, including by many of his 2020 rivals.

Instead of running against the cautious Hillary Clinton, he now faces Kamala Harris, who has avowed support for single-payer health care, and Elizabeth Warren, who has pushed the policy envelope even further with proposals that include a wealth tax. Nearly every Democratic candidate supports a $15 federal minimum wage (something that was a major differentiator against Clinton) and many have praised Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal.

The inclusion of so many liberal candidates threatens to erase what made Sanders’ candidacy unique and attracted so many progressive supporters. And his own supporters and campaign officials acknowledge that to actually win this primary, he’ll need to find new ways to distinguish himself — and fend off a challenge from his new progressive opponents.

“He was the horse leading the cart, and now the cart has caught up to him — at least on some of the rhetoric,” conceded Faiz Shakir, Sanders’ 2020 campaign manager. “The question is whether he can introduce something fresh and continue to lead the cart.”

(Shakir spoke to McClatchy before he was announced as the senator’s new campaign manager, when he was national political director for the American Civil Liberties Union.)

Plus, he’s not starting as strongly as his 2016 performance would suggest. A UMass/YouGov poll released last week found Sanders drawing 20 percent support in New Hampshire, after winning with more than 60 percent of the vote there four years ago. Another survey, from Emerson, found him leading the state, but only with a slim plurality of 27 percent.

“Bernie Sanders is not as strong as you might have thought, for someone who came in second last time around,” said Kathy Sullivan, the former chair of the New Hampshire Democratic Party and the current Democratic national committeewoman from that state. “I see and hear from people who supported him in New Hampshire in 2015, 2016. They’re entertaining others. They’re going and seeing other candidates … they’re not jumping on with Bernie right now.

“With so many other candidates, so much energy, so much diversity, it’s just not going to be the same as it was a couple years ago,” she added.

———

Sanders officials talk about the Democratic field’s leftward lurch as an opportunity.

In their view, a race about taking on corporate greed or instituting sweeping health care reform is a de facto home game for the senator, letting him talk about issues he has spent decades studying, debating and promoting. His deep understanding of those issues, and his tested support for them, will shine through to liberal voters, they say.

“It’s his native language,” said Josh Orton, a veteran Democratic strategist who now works as a Sanders adviser. “He grew up speaking it.”

Orton said that Sanders has spent his career not just learning the talking points about an issue but reviewing white papers about them and working out the details. It’s the kind of sophisticated understanding that might, for example, prevent him from stumbling during a debate over a specific question about single-payer healthcare or raising the minimum wage — moments that could trip up rivals who are less familiar with the issues.

He’s also unlikely to buckle under criticism of his agenda — or face tough questions about why he recently embraced a more moderate agenda.

“The idea that a lot of people may be on the same wavelength this go around is great because we can dive really deep into these policy issues,” said Shannon Jackson, who was the campaign manager for Sanders’ 2018 Senate re-election bid in Vermont. “The senator is an expert on Medicare for All, an expert on the idea of tuition-free college.”

Jackson pointed to videos compiled by Sanders supporters that show the senator giving speeches as far back as 1985, in which he is emphasizing the same issues he continues to talk about today.

That consistency and leadership are important not just as a matter of policy, Sanders advisers say, but for electability, too.

“If you’re not wavering on the fight in the campaign, you’re not going to waver on the fight in the White House,” Orton said. “There is an internal consistency on that that is important.”

He’ll face pressure from liberals to continue to push the policy envelope, especially in a primary that has already seen a proliferation of new ideas.

But Sanders advisers are confident he can do that: The senator has emphasized his plans to combat climate change in the years since his 2016 defeat, and liberals say they think there’s still more room to detail policy plans in that arena. Infrastructure investments — another issue in the Sanders wheelhouse — might offer an area for new ideas.

No matter the challenges, Sanders starts the primary as one of the front-runners for the nomination: He draws almost the second-most support in national polls (behind only the yet-to-announce Joe Biden) and carries over a core of devoted supporters he can count on to back him in early nominating contests of Iowa and New Hampshire.

They’re also ready to once again fund his campaign: Sanders said last week that he had raised $6 million since his announcement a day earlier. Sanders revolutionized small-dollar funding in 2016, raising hundreds of millions of dollars through small online contributions while abstaining from high-dollar fundraisers or donations from the super wealthy.

Those close to the senator argue that in a fractured field, he’s one of the few candidates guaranteed to have the support and resources necessary to even make it to next year’s Iowa caucuses.

“When we get to the end of ’19, just as there always is, it will be very clear there are only three or four who can go the distance,” said one senior Sanders adviser. “And Bernie is going to be there.”

———

If Sanders supporters have reason for concern in the early data as Sanders begins his new campaign, it’s in explaining why a candidate who received more than 40 percent support during the 2016 primary receives considerably less than that in national polls taken today — and whether those former supporters have already decided to back someone else this time around.

“He starts out with a strong hand. His ideas, like Warren’s ideas, are popular,” said Adam Green, co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, which supports Warren. “The question is what numbers will he end with, once he and Biden aren’t the only two with near-universal name ID and voters are exposed to potentially dozens of candidates.

“Other candidates would give anything to have his hand now, but they also have a lot of room to grow,” Green added.

The danger for Sanders is he faces candidates who have not only adopted his agenda but also are younger, female and racially diverse — profiles that might be better suited to voters keen to nominate someone different next year.

“2016 and 2020 are totally different elections,” said Neil Sroka, spokesman for the liberal group Democracy for America. “It’s about the policy agenda, but it is also about the political dynamics of the race. It’s just a totally different world.”