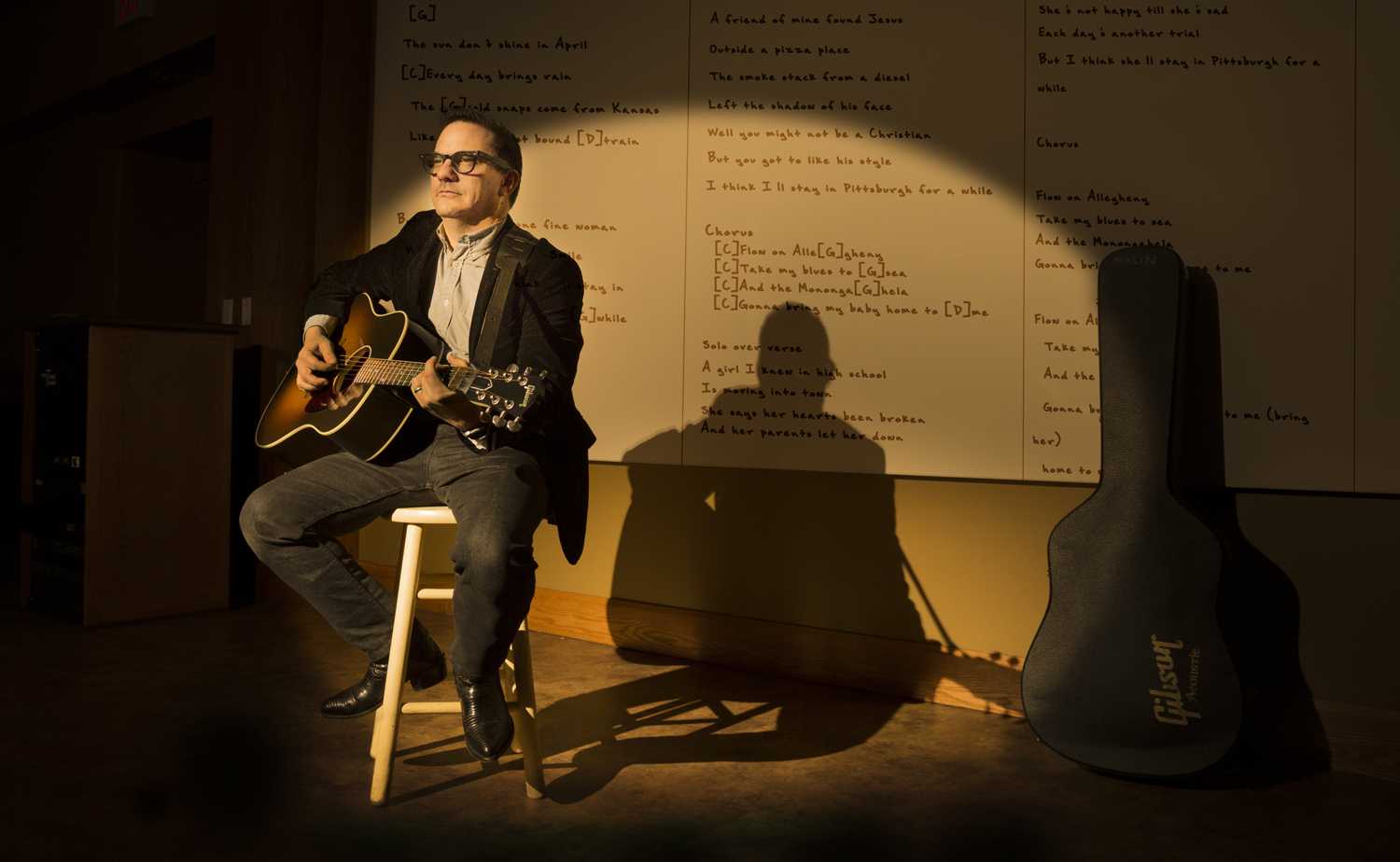

Brent Malin is an alt-country balladeer, but he doesn’t like to advertise it. It’s not common for musicians to hide their musicality, but Malin is not a common man.

That’s why instead of pulling out the textbook and Scantrons in his mass communications process lecture, Malin pulled out a ukulele — breaking his tendency to keep his musicality under wraps and revealing his folk chops to the 160-student class.

Once Malin was in the middle of the song, he realized this part of the lecture was just like any other gig — it was just one his students weren’t expecting to attend. One of the attendees of Malin’s spontaneous performance was Peyton Moriarity, a junior marketing major, who said it was surprising to see Malin break out the uke.

“We’re used to seeing examples of the class material via PowerPoint slides, so it was nice to have some live music in the middle of lecture,” Moriarity said. “I can thank Dr. Malin for brightening up my day.”

Malin’s current discography contains two studio albums that act as musical travel journals, consisting of observations he’s noticed while navigating through life. And while he has serenaded crowds at local venues like the South Side’s Club Cafe and the Thunderbird Cafe in Lawrenceville, Malin likes to draw a line between those gigs and his nine-to-five gig — one that takes place in Pitt’s communication department as a professor.

“[Playing music] is something that I have to do personally just because it’s my creative outlet. It’s my outlet for stress relief. I feel like I need it to keep myself going through life,” Malin said. “I talk about music in my classes, but I have not always talked about my own music or brought it in just because in some ways I don’t know if I’m trying to keep those separate, but it seems a little self-indulgent for me to just come in and start singing songs to the class or something.”

Malin’s office on the 14th floor of the Cathedral of Learning doesn’t seem to belong to a musician. There are no open guitar cases lying on the floor and there’s no sight of a harmonica neck rack on his desk.

Instead, it appears to be the office of any other professor. Hanging on the sliding doors of his office are flyers that promote previous lectures about subjects such as hypermasculinity and post-network TV. Against the wall is a bookshelf lined with neatly arranged books and a framed picture of two young children. A silver coffee pot and a stack of disposable coffee cups are nestled to the right of two computer monitors.

He sits with his back to the monitors, wearing black rim glasses and a black velvet blazer over a light-plum-colored button-down. The only item that really stands out in the office is a framed poster of “Frank,” a piece done by photo-realist painter Chuck Close. For Malin, writing and performing songs is a bit like painting.

“I feel like I need to write these songs because it’s the thing that I do. Some people, they paint in their spare time — this is a thing that they do. And maybe they paint and they don’t ever show them to people,” Malin said. “Right now, I probably have too many songs that I could play in any one show. I would like people to hear them, so that I can just have an opportunity to play them.”

“I feel like I need to write these songs because it’s the thing that I do. Some people, they paint in their spare time — this is a thing that they do. And maybe they paint and they don’t ever show them to people,” Malin said.

Malin grew up in Newton, Kansas, where he enjoyed singing from a young age. He attributes his beginnings in music partly to his family. His parents both sang in the church choir, his mother played piano and his grandfather played guitar — a nylon string model, used for classical guitar.

“When I was 19 years old, the end of my freshman year, my grandfather died — my Grandpa Malin. He was from the Ozark Mountains in Missouri and he had a guitar that he played and he left me his guitar,” Malin said. “I’d never played the guitar before, but I guess maybe I always saw his guitar, which when I was a kid just kind of sat in the corner somewhere.”

While Malin listened to country as a young kid, his music tastes began to evolve as he got older. By the time he was in high school, Malin’s ears leaned toward jazz music and ’80s pop-music. However, though he experiences feelings of nostalgia while listening to music that raised him as a teenager, Malin did not favor the overproduced rock that ruled the charts in the ’80s. Instead, he went back to country music when he moved to California.

“I kind of ran away from country music when I was in middle school … And then somehow it was leaving Kansas and living in San Francisco that I kind of got back into and started writing more basically country music — roots music,” Malin said.

While writing poems as an English major at Kansas State University, Malin also wrote music. Though he no longer writes poetry, Malin constantly writes new material when he can — enough to write “a couple more albums.”

“I was a bad poet, but a good songwriter,” Malin said. “I don’t know if the poems I wrote were too cliche and then they lead to songs that were actually just about right somehow. Cheesy poems make good songs or something like that.”

Brent Malin

Malin describes his songwriting process as natural and free-form. He said he usually writes the lyrics and music at the same time. To stand out as a musician, Malin focuses on writing solid lyrics and “putting himself into the song” when performing live.

“I guess if I had to classify [my lyrics], they’re kind of like folk songs just in the form.”

He took a long pause.

“I don’t know, I wouldn’t mind writing a pop [song],” Malin said. “I would probably say it’s actually if I decided — alt-country. Probably. Or roots rock. It’s kind of an Americana kind of vein.”

Malin emphasized these musical styles on his two records, “Long, Long Way” (2007), recorded in San Francisco and “Two Trees” (2013), recorded in Pittsburgh. For his first album, Malin recorded alongside a band he assembled, known as the Railroaders, which was notable for the rare inclusion of a pedal steel guitarist.

“The bass player moved to Nashville and the drummer moved to Africa and I don’t remember what happened to the pedal steel guitarist I was playing with,” Malin said. “[Pedal steel guitar] is the thing that a lot of people think they hate about country music — the twang. And it’s the twangiest of the twang.”

“[Pedal steel guitar] is the thing that a lot of people think they hate about country music — the twang. And it’s the twangiest of the twang,” Malin said.

He admits that life with a family has slowed down the frequency of local gigs compared to when he first moved to Pittsburgh from San Francisco with his wife. As a father of two, an 8-year-old and a 5-year-old, he must balance life as a father and life as a college professor. But his songwriting inspiration comes at a time when he is most preoccupied with his life outside of music.

“Somehow, it’s like in the busiest moments, I end up writing more,” Malin said. “I don’t know if it’s just things seem very frenetic and my mind is working faster or I just need a little bit of a release.”

It was students who were in need of a stress release this semester that made him reconsider his tendency to avoid incorporating his music into lectures. In one of Malin’s Mass Communication Process lectures, the class discussion was based on Theodor Adorno and his theories of music.

“He’s writing about the music of the 1920s and ’30s and I was thinking, ‘You know what? I could play some songs from the 1920s and ’30s to kind of make the point of what he’s reacting against,’” Malin said.

The ukulele “method” made the lecture topics more interesting — and it was a method to de-stress students before the exam scheduled for the next week.

“I have to say, honestly before I was nervous about it,” Malin said. “I don’t know how they were going to react.”

Jack Schneider, a sophomore marketing and supply chain management major, said he knew Malin had a strong knowledge of popular culture from the past and present, but he was not expecting Malin to adjust the direction of the lecture to include a musical act.

“I think that’s gutsy, but I can’t say that I was surprised to learn that Malin played the ukulele,” Schneider said. “I always got the impression that he was a jack of all trades and so this tracked for me.”

Malin said he transitions the energy he feels from performing music into speaking in front of his classes. He believes performing at a show is a process of “connecting with your feelings” and “connecting with people around” those feelings.

“I played a show at The Bitter End in New York, and so I remember when I was playing there, there was a big sign on the wall of people who played there before,” Malin said. “A whole bunch of people and it says ‘and many others.’”

For now, Malin will settle for the office nameplate outside his door on the 14th floor of the Cathedral — a sign that he doesn’t have to share with anyone.

“And I remember thinking, ‘Hey, now I’m one of the many others. There I am,” Malin said.