Pitt Men’s Study reflects on past, future of HIV fight

June 5, 2019

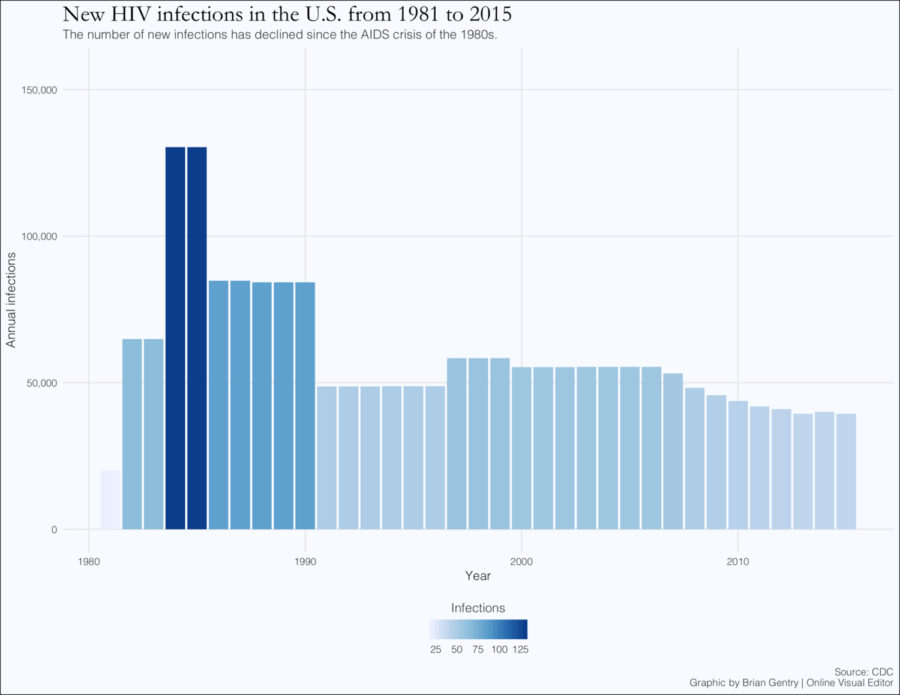

When an outbreak of sexually-transmitted human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, hit the United States in the early 1980s, not much was known about the virus or how it spread. But scientists, researchers and volunteers at Pitt have been working for almost four decades to try and change that.

The Pitt Men’s Study was formed in 1984 and has followed almost 3,000 separate cases of HIV with the goal of determining the causes of the virus and then finding treatments and cures.

Dr. Mackey Friedman, a PMS co-investigator, said in an email participants attend semi-annual study visits, some of whom have not missed a study in 35 years. Participants, who are accepted on a rolling basis, range from young to old and are subject to blood testing, clinical trials and regular interviews.

While deaths caused by HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS, which often follows, have dramatically decreased in the last decade, a cure has yet to be found. The National Institutes of Health is the largest public entity currently working towards a cure, and PMS operates as a branch of NIH’s ongoing work.

The outbreak didn’t occur in the distant past — a few cases of HIV popped up in the United States in the ’70s, but by the ’80s, the virus was spreading across the country.

William Buchanan, the clinical coordinator of PMS and member of the program since 1988, said the decade was marked with uncertainty.

“Men were becoming ill and dying of these very strange diseases that nobody ever heard of, nobody ever understood why,” Buchanan said. “There was a panic and an urgent need to do something about it.”

Buchanan said bars began using plastic cups instead of glasses in fear of spreading the virus. Sex education classes increased at the behest of then-Surgeon General C. Everett Koop and homophobia skyrocketed.

One of the significant issues surrounding the epidemic is the stigma. During the initial outbreak, infected men either did not know they had contracted HIV or were uneasy about coming forward due to the surrounding controversy. Furthermore, speculation over the virus’ causes created a dangerous environment for those infected.

“There was a lot of distrust with the government,” Buchanan said of the time period. “People were reluctant to have it known that they were infected or that they were gay.”

At a World AIDS Day event in late November, scientists, researchers and members of PMS gathered at Heinz Chapel to commemorate those lost to the disease.

Dr. Charles Rinaldo, principal investigator of PMS, commended the first 60 men that came forward to participate in the study.

“It was 1982, at the beginning of the epidemic, when fear of AIDS was rampant, when 60 gay men in Pittsburgh answered our hand-drawn recruitment posters,” Rinaldo said. “Without those 60 men, there would be no Pitt Men’s Study.”

As the patients have aged, PMS and its goals have also changed.

Buchanan said that the goals of the study, originally to understand the causes of HIV and how it spreads, have evolved into keeping those infected healthy so they may live longer lives. PMS has accomplished these newer objectives through clinical trials and substudies.

He added that PMS has found HIV-positive men now live much longer and healthier lives compared with in the past due to new treatments created since the late ’90s in conjunction with NIH and the national Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.

Dr. Jeremy Martinson, a PMS co-investigator since last year, said research at PMS has recently focused on understanding and treating complications that HIV-positive people encounter as they age.

“People who have been infected with HIV for a long time, such as many decades, have greater health problems as they age. They are at greater risk of heart disease, stroke, cognitive problems, and even some cancers,” Martinson said in an email.

PMS has seen the presence of HIV plummet in its patients, but not entirely disappear, due to the virus latching onto cells in spots that current medicine cannot reach. As a result, scientists at Pitt’s Graduate School of Public Health announced in an April press release they had created a new treatment, dubbed “kick and kill.”

Dr. Robbie Mailliard, a lead scientist in the effort, said the method works by “kicking” the virus out of the hard-to-reach locations and then killing it. The scientists primed dendritic cells, a component of the immune system, to attack and destroy certain T-cells, another component of the immune system, which HIV uses to hide itself from detection.

“There are some promising therapies being developed for the kill,” Mailliard said in the release. “But the Holy Grail is figuring out which cells are harboring HIV so we know what to kick.”

Buchanan said PMS has achieved a successful “kick and kill” operation in a test tube and is looking forward to a clinical trial.

The American public has accumulated a broader comprehension of HIV, its risks and its causes because of scientists like those at PMS. As a result, the stigma surrounding the virus has dropped considerably since the troubling times of the ’80s.

Martinson said the study has faced challenges like funding shortages, failed trials and a lingering prejudice against people living with HIV/AIDS, but said the volunteers have always gone to great lengths to participate.

“Many of them have been enrolled in that since the mid-’80s but still come into our clinic twice a year to give blood, answer questions and take part in research studies, for little reward beyond parking validation,” Martinson said.