Column | College athletes should take ownership of the business they sustain

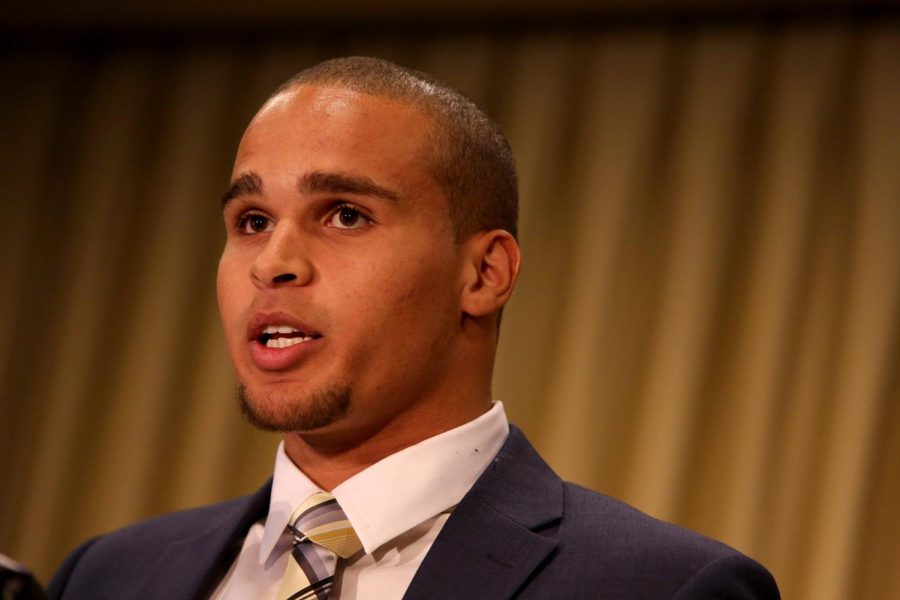

Antonio Perez, Chicago Tribune | MCT

Kain Colter, a quarterback and receiver who completed his college football career in 2013, announced that several Northwestern football players wished to join a labor union during a press conference at the Hyatt Regency in Chicago on Jan. 28, 2014.

August 31, 2020

Pitt’s Oakland campus is currently quieter than it normally is as summer turns to fall. Fifth and Forbes avenues are less densely populated as the University community and its neighbors try to social distance and prevent the spread of COVID-19.

But on Pittsburgh’s South Side, the crack of pads and shriek of whistles cut through the air — the Pitt Panthers are practicing in anticipation of an altered college football season. Ten games — all in-conference and in front of no fans for the time being — are scheduled for the Panthers in 2020.

Meanwhile, the start of in-person classes has been pushed back to Sept. 14. Pitt feels it’s safe enough for football players and staff to gather in the hundreds on a field and in a practice facility, but not safe enough for them to go to classes with few students.

In doing so, Pitt and scores of schools across the country circumnavigate a truth that has been apparent for decades — college athletes are professionals being used as a cash cow for their schools.

Alabama football head coach Nick Saban — one of the sport’s most successful figures in history — sees no issue with treating players like the professionals and letting them choose to play football through a pandemic.

“But our guys aren’t going to catch [the virus] on the football field,” Saban said. “They’re going to catch it on campus. The argument then should probably be, ‘We shouldn’t be having school.’ That’s the argument. Why is it, ‘We shouldn’t be playing football?’ Why has that become the argument?”

Saban said in no uncertain terms that he sees sports as the priority for “student-athletes,” especially for the football and basketball players who bring in large sums of athletic department revenue.

The risks the COVID-19 pandemic poses have exacerbated the unfair power disparity that exists in college sports. From waivers meant to free individual schools of liability should a player die or suffer long-term health defects after contracting COVID-19 on campus to allegedly lying about safety precautions, college football is doing all it can to push through to a 2020 season.

Money reigns supreme. The average college football season brings in roughly $4 billion in revenue nationwide, and when that money is threatened, colleges will do what must be done to protect it.

Football is a unique sport — it requires a lot of manpower and time on behalf of the players, coaches and operating staff. While wildly different sports and contexts, the success of the “bubbles” created by the NBA and WNBA have some questioning whether or not college sports could do the same and play a season isolated from the rest of the world.

The NCAA clearly had the desire to play this season, But there is one major problem standing in the way — the question of professionalism.

The NCAA has become infamous for their coining of the term “student-athlete.” A completely fabricated term, “student-athlete” has been used to deny college athletes the most basic of rights that anyone who performs profit-producing labor deserves — fair pay, name, image and likeness rights and health insurance being the most glaring omissions.

Putting players in bubbles would further reinforce how absurdly skewed a college athlete’s schedule is toward their sport. The “student-athlete” label is the NCAA’s most powerful weapon against compensating college athletes for their labor. And the creation of a bubble would only tear down that term’s power and further demonstrate that college sports and athletes have a special place in the ecosystem of a large university.

Rather than do what has proven to make sports feasible, the decision has been made to put players, coaches and support staff at risk and avoid giving athletes any more ammunition in their fight for fair compensation.

But football players, the NCAA’s most productive employees, are pushing back. They are harnessing the power of collective action. Five years removed from former Northwestern quarterback Kain Colter’s attempt to start a college football players’ association, the players are taking matters into their own hands.

Threats to strike began in mid-summer and continued through August. Players at the University of Texas at Austin threatened to skip recruiting duties if the football program and school did not meet certain demands to remove racist symbols. Current and former Pitt players put pressure on head coach Pat Narduzzi to apologize for his use of the word “thug.” And most recently, players from the Pac-12 and Big Ten conferences threatened to sit out the 2020 season if athletic departments did not employ uniform COVID-19 safety measures.

It’s one thing for college sports to be profitable, but for the NCAA to continuously tote the purity and morality of its enterprise while denying its workers what they deserve is unjust.

You want sports during a pandemic? Fine. But they’re subject to the will of the young men and women who make them possible.