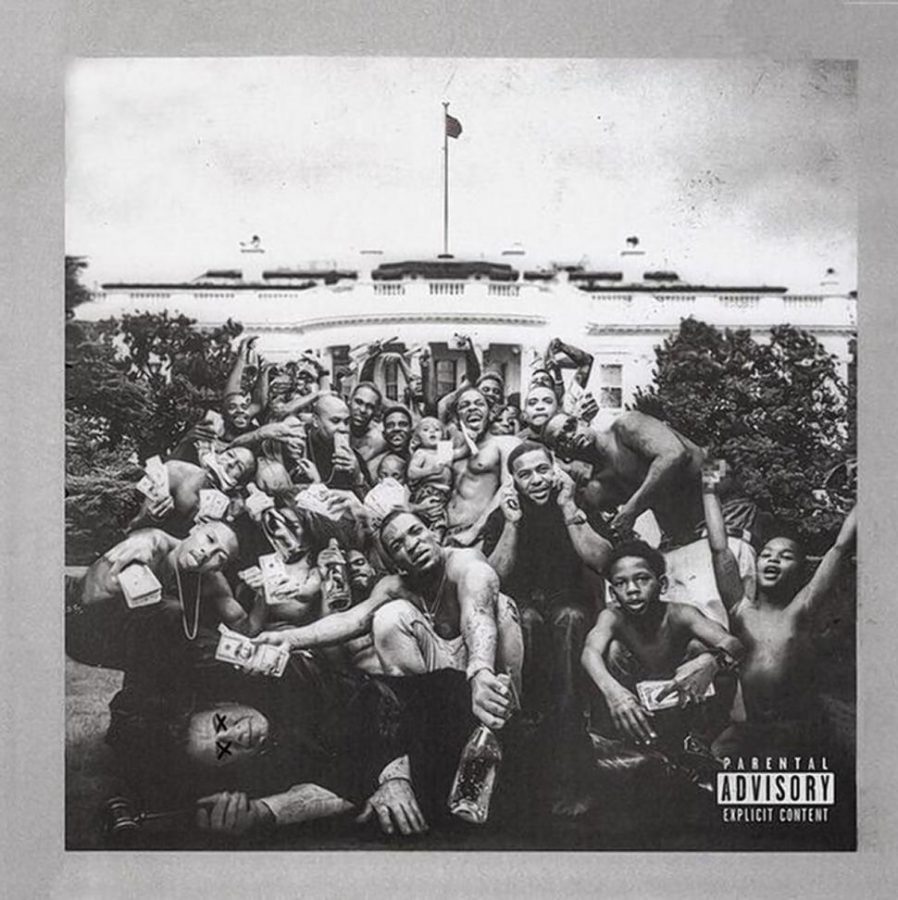

Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Butterfly’ a rich, vitriolic masterpiece

March 19, 2015

Kendrick Lamar

To Pimp a Butterfly

Grade: A

Earlier this year, New York pop critic Sasha Frere-Jones left his post to become executive editor of the user-generated lyric annotation website Genius (formerly Rap Genius). In an interview with Newsweek, he said that his goal for the site was “raising the standards for all the annotations, bringing in different layers of meaning.” If that statement is truly the salvo that it sounds for a soon-to-be utopian literary community, Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly is how it’s going to get there. It’s worth noting that, not three days after the surprise release of the Compton rapper’s tough and funky new album, his fans have annotated more than 99 percent of its lyrics.

As Lamar’s profile increases, his work only gets knottier and hits higher concepts. His debut album, 2011’s Section.80, had serious political and confessionalist tendencies, plus a loose narrative about two women named Tammy and Keisha that won the admiration of not only hip-hop purists, but the general underground. But Lamar was still tempering his eccentricity at that point. His voice sounded affectedly low and aggressive, and for every genre-bending emo track, there was a hook-verse “I’m-good-at-rapping” counterpart.

This made the plot seem feeble, at least compared to his 2012 cinematic breakthrough album good kid, m.A.A.d. city, which earned him plenty of rave reviews, Grammy nods and guest spots, ranging from his scene-demolishing verse of Big Sean’s “Control” to his most likely profitable appearance on Robin Thicke’s “Give It 2 U.” On To Pimp a Butterfly, he has not backed down one bit. Mischievous but never playful, angry but never blind and smart but never pretentious, this is Kendrick at his most puzzlingly Lamarian (because, let’s be honest, he deserves his own adjective by now).

The opener “Wesley’s Theory” establishes much of the album’s musical palette. It begins with a crackling loop of buttoned-up, string-kissed ’70s soul that repeats “every n*gger is a star,” before launching into an instrumental that demonstrates masterful choice of collaborators. He triangulates modern funk by incorporating the afrofuturistic synth work of Parliament’s George Clinton, the sample-happy gangsta-ness of executive producer Dr. Dre (who praises Lamar in a voicemail interlude) and the brainy fusion of Flying Lotus and Thundercat.

The result is one of the most joyously funky things you will ever hear, but the lyrics are a vehement treatment of privilege. “What you want you? A house or a car?/ Forty acres and a mule, a piano, a guitar?/ Anything, see, my name is Uncle Sam on your dollar/ Motherf*cker you can live at the mall,” Lamar intones in his trademark voice, a hypnotic, throaty countertenor that has somehow not prevented him from becoming massively popular. His language is dense. He seems to criticize capitalism’s effects on reconstruction, art and race relations, yet he admits to its seductive power. Believe it or not, it’s probably the most tame and coherent song on the album. There’s no “B*tch, Don’t Kill My Vibe” for white dudes to do acoustic covers of anywhere here.

“For Free?” sees Lamar channeling the late black liberation writer Amiri Baraka, spitting a vitriolic high-speed collision of high and low culture over two minutes of mercurial free jazz that recalls early Ornette Coleman. Here, Lamar reveals the ascetic and militant politics of the 1960s black left and hip-hop’s dream of liberation through excess as two sides of the same cultural coin. He then arrives mercilessly at “Oh America, you bad b*tch, I picked that cotton that made you rich.”

The remainder of the album rearranges lyrical and musical elements of the first two tracks. Yet, it never settles down — the music is constantly finding new vantage points, new emotional and rhetorical positions that make the album’s 70-minute runtime feel about half as long. The near-schizophrenic malleability of Lamar’s voice plus the choice to supplement the programmed beats with live musicians keep everything fresh.

Lyrically, there’s just as much devotion to variety. “For Sale?” and “i” are both songs about love among abject poverty, but the former pins self-destructive romance against Burt Bacharach flugelhorns and canned Latin percussion, while the latter uses a fiery Isley Brothers sample to profess liberatory self-love.

When lyrics are repeated, it’s not because they’re clichés — it’s because this album is a massively interconnected concept album. Motifs and characters abound, but one formal element is particularly notable. For one, Lamar performs a poem beginning with the line “I remember you was conflicted” in between songs, each time with a few additional lines until the 12-minute closer “Mortal Man.” There, he delivers the poem to completion, and it’s revealed that he was presenting it to 2Pac, who responds with clips from a 1994 interview conducted just two weeks before his death. It’s a little heavy-handed, but that might just be because it’s the ending to a concept album whose concept we have yet to pin down.

Even with its limited sonic and thematic palette, To Pimp a Butterfly is Kendrick Lamar’s richest listening experience yet. It’s also a puzzle whose pieces lack annotation into a greater whole, which makes it difficult to evaluate.

But most of what it does, even in its most provocative moments, it does tastefully. As long as he keeps giving us beats as moving as “How Much A Dollar Cost” and lines as crushing as “Would you know what the sermon is if I died in this next line?” we’re blessed to have him still alive and rapping.