Pitt professor wins astronomy award for simulating galaxies with ‘greater clarity than ever before’

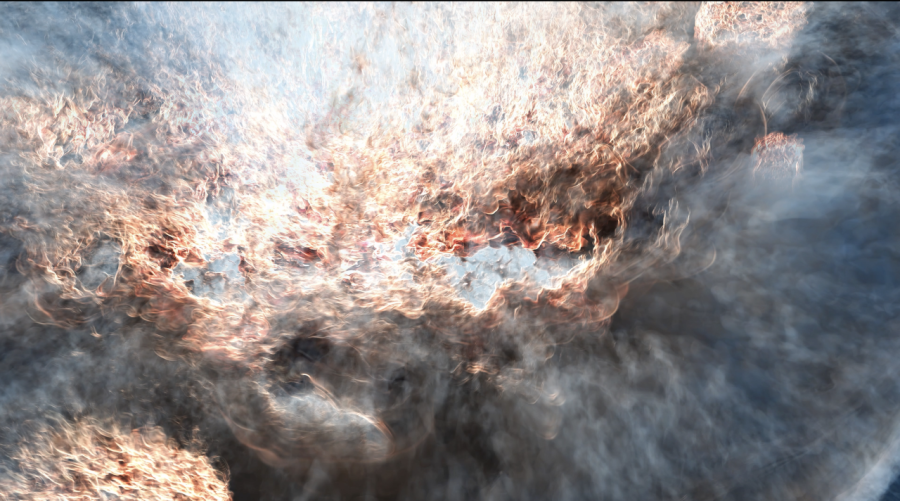

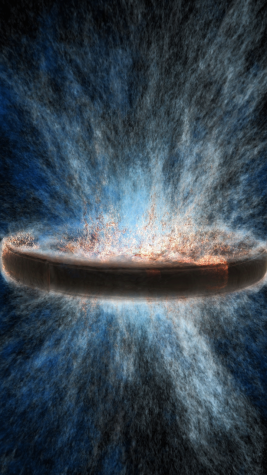

Image courtesy of Evan Schneider / NVIDIA IndeX

A simulation of astronomical phenomena depicting emission of gas in space created by Evan Schneider’s computer program.

November 2, 2022

Evan Schneider has invented code to look at and understand how galaxies behave in incredibly precise detail by harnessing the potential of cutting-edge supercomputers. One of the images taken from her simulations depicts a massive disk galaxy emitting gas into space.

“This is just a disk of gas, basically, with stars embedded in it that are going off as supernova explosions, ” Schneider, an assistant physics professor, said. “There are little clouds where stars form, but then they explode, and they carve out these big bubbles in the disk of the galaxy that then drive gas back out.”

Schneider is the first person from Pitt’s astronomy department and the first woman from Pitt to win the Packard Fellowship. She received this nationwide award in October for her groundbreaking code “Cholla” — Computational Hydrodynamics on II Architectures — used to simulate incredibly complex astronomical events.

In 1988, the Packard Foundation created the Packard Fellowship Award to support “inquisitive” and “passionate” scientists and engineers from the United States. Each year, 50 universities nominate two aspiring professors to compete for the award, of which 20 fellows are selected to receive grants of $875,000 over five years.

Schneider’s creations simulate interactions between massive celestial bodies that take millions of years to occur in nature, but with her code, Schneider said she can visualize them from beginning to end by simulating them on a supercomputer.

“You can’t observe this. You observe many galaxies in different stages of the process,” Schneider said. “But the simulations are how you actually get to see it all unfold.”

Arthur Kosowsky, chair of the physics and astronomy department, said Schneider’s code is now running on the world’s fastest scientific supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Lab. Kosowsky said the impact of Schneider’s work is of historic proportions.

“She is poised to produce the best simulations of galaxies ever made,” Kosowsky said.

Schneider found the path she wanted to pursue while studying the universe through telescopes and equipment at observation sites.

“When I went observing, I was with someone who had been observing for many years, and he was so worried about the weather and he was just constantly checking his phone,” Schneider said. “Are there going to be clouds? Are we going to get rained out? I very quickly realized that observing really wasn’t for me.”

Shortly after her time observing galaxies, Schneider started getting into modeling them on computers instead, where she found the “control” she lacked when trying to observe them in nature.

“I realized I really liked modeling, because sure, things could still go wrong, there could be bugs in my code, I could run a simulation and it doesn’t go the way I expect, but everything feels like it’s under my control,” Schneider said.

Robert Caddy, a graduate physics student focusing on high-performance computing, worked closely on Cholla alongside Schneider and her team. According to Caddy, no previous code in astronomical modeling can simulate as efficiently as Cholla due to its ability to harness the graphics processing units of supercomputers, which make up the most of their processing power.

Schneider said Cholla is a software adapted to a “new hardware space.”

“The software that I built [Cholla] was designed to take our existing formulas and move them over into this new hardware space so that we can do things basically faster, and it worked out really well,” Schneider said.

Helena Richie, another graduate student working on Cholla, said no other program matches Cholla’s accuracy. Each image Cholla produces is made of trillions of small cells, allowing scientists to precisely observe patterns.

“What makes Cholla so unique is that we’re able to simulate an entire galaxy, its surrounding environment, because each individual cell in the simulation is the exact same size,” Richie said.

As the first woman to receive the honor at Pitt, Schneider said Pitt’s physics & astronomy department lacks women and minorities at top levels. She feels like she’s “pushing the balance of things” by winning the Packard fellowship.

“At the graduate student level there are lots of women, but by the time you get to the rank of tenured professor, it looks different,” Schneider said. “It’s also worth mentioning, you know, that … it’s not just women that are missing from the field, we’re missing other people with minority status.”

Richie said working with Schneider has helped her gain confidence in her work, despite being a minority within the field of physics.

“I have had interactions with people who wanted to be elitist and discourage me,” Richie said. “I definitely did not believe in myself as much as I do now, and I really think that a lot of that has to do with having Evan as my adviser and kind of a role model.”

Schneider said above all, astronomy is a “team science” and also credited her team for the award.

“Astronomy is a team science, almost everyone works in teams or collaborations,” Schneider said. “The idea of claiming credit for something yourself is not really how the field operates.”

According to Kosowsky, Schneider and her team’s work will have a tremendous impact on the

future of the field.

“These come at an important time,” Kosowsky said. “The new James Webb Space Telescope is providing unprecedented observations of the earliest galaxies, and Evan’s simulations will be key to understanding the entire history of galaxy formation in the universe.”