Pitt researcher Xinyu Liu hopes to someday see a sick person figure out exactly which pathogen is causing their illness just by visiting their local pharmacy.

Concluding a two-year study, Xinyu Liu, an assistant professor of chemistry, and Sanford Asher, a distinguished professor of chemistry, have found a way to pinpoint the culprit of an illness within minutes using microscopic sensors.

“Imagine you can pick up a kit in CVS … to see if yourself or your close family members are infected with some nasty bacteria,” Liu said. “Take out the kit, put it in their mouth or expose it to their body fluid. A few minutes later, based on the color, you get a sense whether you are bugged and whether you should go to see the doctor.”

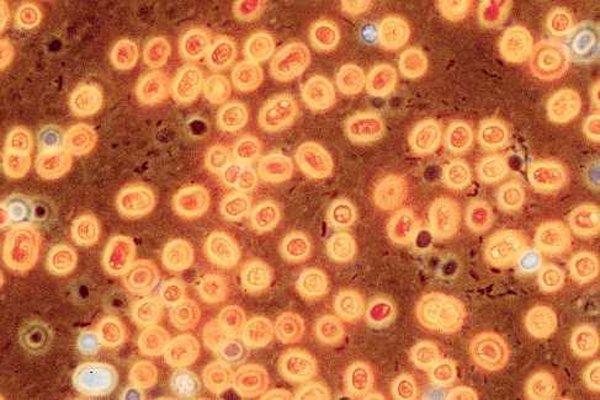

When the sensor detects a pathogen, an infectious agent such as bacteria or fungi, it attaches itself to the surface of the infected cell and emits a ray of colored light that varies with the type of pathogen. Currently, the sensor only works on the fungus that Liu and Asher used in their study — Candida albicans, which causes oral thrush and yeast infections.

According to Liu, doctors often prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic when a patient has an infection until a doctor or technician can take a sample of bacteria from the body, swab it into a petri dish and wait for it to grow.

“You can do a swab and culture the bacterium or fungi, but that takes days,” Liu said. “You can examine the DNA, but that takes another day or two. It’s a pretty tedious process.”

Liu and Asher conducted their research in the Chevron Science Center. The University of Pittsburgh and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency within the United States Department of Defense funded their two-year project, which Asher estimates cost $100,000 per year, or $200,000 in total.

“If we have a panel of pathogen-specific sensors, I believe they will be very useful tools in the clinics or for personal care,” Liu said.

Liu and Asher based their method on the diffraction, or composition of different colors, of light from their sensors. The diffracted colors change upon the interaction of the pathogen with the sensor. Liu and Asher have developed a protein hydrogel in which a protein polymerizes — when smaller proteins come together to form larger proteins, which coalesce into a responsive film.

The hydrogel, which swells in water, is specific to Candida albicans.

For patients more susceptible tooral thrush and yeast infections, these fungal infections can be life-threatening. For doctors and lab technicians, Liu and Asher’s method lets them figure out which pathogen is causing the illness by monitoring the color of light diffracted by the sensor. The sensor, made of proteins and carbohydrates, reacts to the infectious bacteria and emits a ray of light almost immediately.

With Liu and Asher’s method, every time a researcher screens a pathogen, he or she must use a laser point and a different hydrogel sensor. Because of its minimal equipment requirements, hospitals and clinics will not have to spend a lot of money up front to implement Liu and Asher’s technique, according to Asher.

Liu said he and Asher plan to expand their research to include Escherichia coli, to combat food poisoning, and Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), to cut down on infections.

David Nace, leader of a UPMC study on antibiotic overuse and resistance, said doctors in hospitals could use the new technique to monitor multiple patients with similar illnesses.

“It could be used in active surveillance in hospitals when looking for problem organisms such as MRSA and VRE [Vancomycin-resistant enterococci],” Nace said.

Nace does not think Liu and Asher’s research will directly affect his own, which focuses on urinary tract infections in nursing homes. If Liu and Asher, or other researchers, expand the technique to viruses such as influenza, however, it could be incredibly helpful.

In terms of real-world benefits, Liu imagines the take-home test kit and the help it will provide to everyone in all parts of the world. Liu and Asher said the kit is a far-out dream but not one they plan to give up anytime soon.

“The impacts will be tremendous,” Liu said.