Hilton Als discusses provocative new work

January 28, 2014

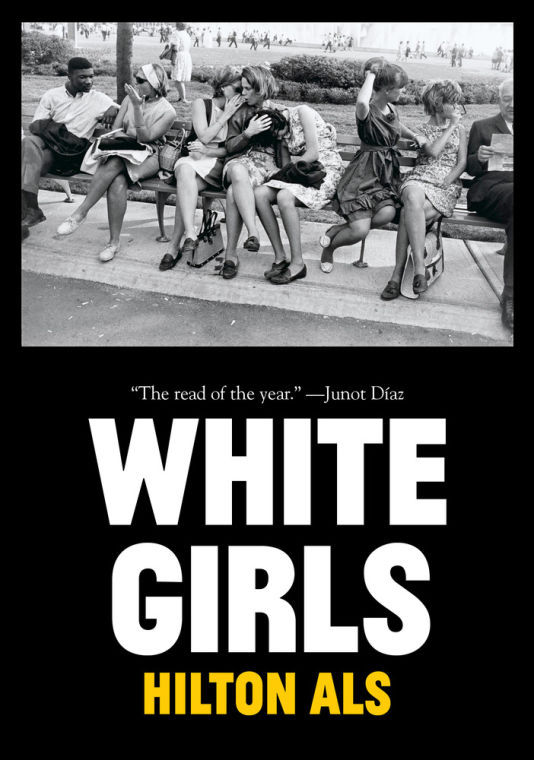

The internal dissonance of a song cutting out before its climax is the best way to describe what it feels like setting down “White Girls,” the latest collection of essays by New Yorker critic Hilton Als. His prose, as rhythmic as it is hypnotizing, makes attempting to read his book in chunks, as opposed to one fell swoop, a conscious act of restraint. In the book, Als takes the blush-worthy title to unexpected realms, focusing on subjects including Eminem, Richard Pryor and Malcolm X.

Als held a lecture last night at 8:30 p.m. in the Frick Fine Arts Auditorium, but I was able to speak with him before his stop at Pitt, touching on a number of topics concerning his own writing.

In our phone conversation, Als spoke carefully but freely about the topic. With a book title as striking as “White Girls,” I initially got the sense that the obvious question of “What!?” had been asked so many times that his explanation had become almost second-nature. As we spoke, however, I realized that his ostensible preparedness was simply a result of a deep fascination and reverence for the subject.

The Pitt News: “White Girls” is gaining popularity, which is in a lot of ways rare for a book of this type. How do you feel about the reception it’s received?

Hilton Als: It’s a very interesting feeling because I think in order to remain un-self-conscious, it’s important to not start reading about yourself, because if you start reading about yourself, you start behaving and changing your behavior to fit what you’ve read. But I am really happy, not so much as people like the book as much as people are thinking about it. I feel very touched by the attention the topic is receiving. Even if people didn’t like it, they are at least interested in it.

TPN: On the Internet right now websites are, albeit badly, clamoring for content around issues such as the ones presented in your book. Do you think something like this, a long-form work, is something that more people will start gravitating towards?

Als: I don’t know if there is a lot to be said for how books should or should not be received. I read books to be provoked or to think or to feel, and I feel like there is a lot to be said about the fact that there is an audience out there for books that matter and engage people intellectually.

TPN: You are a theater critic at The New Yorker. Has there always been an intellectual draw for you to matters of art and culture in your writing?

Als: I think as a writer and a thinker I’m really sort of drawn to people and works that are very much about taking risks, whether that be in form or emotional content, and I think there is a lot of support out there for people who want to be supported because they are taking risks that they are not self-conscious about. I really like people that are not provocative on purpose.

TPN: Your writing has a sort of rhythm to it that in a lot of ways harkens to theater — is that a natural element to your writing?

Als: I’ve always been interested in how language is alive and how you keep it alive and not kill it on the page.

TPN: What, in terms of this book at least, is a “white girl?”

Als: I think that it has less to do with race as it does with position. A lot of the strides that feminism has made in the last 50 years have to do with equality in the workplace and financially, which still doesn’t happen a lot, but there are more women in power than when I was coming up. I think one of the splits that happened between white feminists and black feminists was that a lot of black women had to act as the heads of the households, while white women were still trying to fight against the patriarchy. I think a lot of those differences are shrinking, and as a result, a lot of white women are becoming more vocal and powerful in the workplace, which comes with its own set of social changes and issues — one of which is, “How do we deal with marginalization and visibility?” At the same time, I wanted to pick a fraction of society in that title and in the stories I tell who does have a certain amount of power because she can pass, but at the same time, marginalized power because of her gender.

TPN: Is there a parallel between black male marginalization and that of white women?

Als: I think the comparison I was making in the book is that white women can sometimes identify culturally and spiritually with black men. I think that also, I was trying to draw a rejection of that dialogue of marginalization. I think that it’s a complicated relationship and one worth exploring more openly. Lets call it shades of difference, and in those shades there are very complicated emotional structures.

TPN: Do you think any of the contemporary voices dominating the media circuit now are adding to that conversation?

Als: I think there are more people writing because there are more opportunities, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the writing is good or the thinking is good. I think there are moments within that of great validity. I can say specifically that there are a lot of younger writers who are coming up who are fantastically ambitious and continuing that dialogue.

TPN: You were one of very few critics of color to come in defense of Lena Dunham’s “Girls” and the accusations of “unrealistically” portraying an all-white New York City. How do you feel about the criticism of her show?

Als: I don’t think that blackness or whiteness needs to be a part of every conversation. She is describing her world. I’m not a part of her world. If I did a show she wouldn’t be a part of my show. I just don’t think that anyone is obliged to talk about things that they don’t feel. I think there is so much fogging through the politically correct mud field that kills a lot of art. I think her show is great and doesn’t need to drag me into it to make it any better.

TPN: Speaking to trudging through political correctness in creating art, do you think a rejection of that was a part of naming the book “White Girls?”

Als: I think subconsciously that was definitely part of it. I just thought it was a funny title for a book. I think we’ve lived in a society where blackness was self-defining. I mean we have “Invisible Man,” “Black Boy,” “Tar Baby,” what about turning that experience around? What if we took something else and turned the table on that? I just thought it was about time.