Elimination of University yearbook fits trend

November 14, 2013

Cherish the memories, for the printed pages of the University yearbook have come to an end.

In September, the University decided to no longer produce “Panther Prints,” its yearbook, which was first published in 1907 under the name “The Owl.” In its place, Pitt will offer a free digital photo album to chronicle student events that will include an interactive feature allowing students to upload personal photos. While students and alumni have not reacted unfavorably to the decision, yearbook experts said the negative impact will become more apparent decades from now.

Pitt is not alone. Large universities are increasingly dropping their yearbook publications. The University of Virginia and Purdue University, both schools with more than 20,000 students, stopped production on their yearbooks within the past five years. Lori Brooks, associate executive director at the College Media Association, said there is no correct data available on the mortality rates of yearbooks, but student interest has been waning since the ’80s.

Shawn Ahearn, director of communications for Pitt’s Office of Student Affairs, and Janine Fisher, communications manager for Student Affairs, approached the Student Government Board in September with low yearbook sales data and proposed a search for an alternative.

Last year, only 114 of Pitt’s more than 3,500 seniors registered to receive a free online copy of “Panther Prints,” and 40 seniors purchased a hard copy for $50.

The Board has funded the annual publication of Panther Prints with roughly $41,000 through a 1.6 percent allocation from the Student Activities Fund each year. This posed a problem for Ahearn.

“We cannot justify spending the amount of money, time and energy to produce a piece for which there is such minimal demand,” he said.

Board member C.J. Bonge estimated that the online photo album production would reduce the cost to about $10,000 to $12,000, according to an article previously published in The Pitt News.

The possible production of a “traditions book” for first-year students detailing campus could use a portion of the remaining funds, with the rest returning to the Student Activities Fund.

Laura Calhoun, a senior English writing major and current editor of “Panther Prints,” said her staff is excited about the photo album, which will launch in the spring semester. Calhoun said she thinks the format will be more accessible to students, who will have access to the album throughout the year because the staff will continuously upload pictures.

Four faculty members and 18 students worked an estimated 1,200 hours to produce last year’s yearbook, Ahearn said. The online album will require less writing and graphic design by the staff members because they will only post photos with headlines, rather than more detailed information about the individuals in the photographs.

Brooks said that photographs are only a piece of the story that a yearbook tells. Brooks said she does not think the photo album will effectively depict the full story behind an event without the accompanying articles that provide history and perspective.

Corrine Satriano, former 1999 and 2000 editor of the yearbook, felt similarly.

“The photograph doesn’t always elicit the same emotional response that the article does,” Satriano said.

Ahearn agreed with Satriano, but said that including articles would drive up the cost. The photo album method reduced the amount of manpower needed, and the University currently pays Calhoun and two photographers to work on the online album.

The Publications Advisory Board oversaw both “Panther Prints” and The Pitt News before Student Affairs took over yearbook operations. The University’s Board of Trustees appointed faculty and professionals to the advisory board, which worked independently from the University.

In 1999, the Office of Student Affairs took over the yearbook’s management. The Publications Advisory Board, renamed The Pitt News Advisory Board, became responsible for overseeing solely The Pitt News.

Satriano said students lost control of determining layouts, theme and word count of the 2000 edition of the yearbook with the change in management.

Lillian Thomas, assistant managing editor of special projects at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, was chairman of the advisory board in 1999. Thomas said the board members debated whether to continue funding the yearbook throughout the year.

“We thought that if the administration or the yearbook staff wanted to keep [the yearbook], it needed to be under some other kind of management,” Thomas said. “We didn’t feel that the numbers showed we should it support it.”

An increasing trend

Pitt is not the first major university to stop producing its yearbook.

In 2010, the University of Virginia, located in Charlottesville, Va., stopped publication of “Corks & Curls,” which maintained a nearly 120-year history at the university before its demise.

In 2008, Purdue University, located in West Lafayette, Ind., canceled publication of its yearbook, “The Debris.” For the final edition, Purdue’s yearbook staff ordered fewer than 1,000 copies to distribute. Its total enrollment comprised 38,788 students last year.

Ray Mina, a spokesman for TreeRing, a yearbook company based in San Mateo, Calif., and founded in 2010 that creates both physical and digital editions of yearbooks, said yearbook sales have been declining across the nation.

“I think part of the problem is that at a large university like the University of Pittsburgh, you have a lot of students, and the yearbook needs to be about the entire school population,” Mina said. “If you have more than 20,000 people that you are trying to represent, how relevant is it to any one person?”

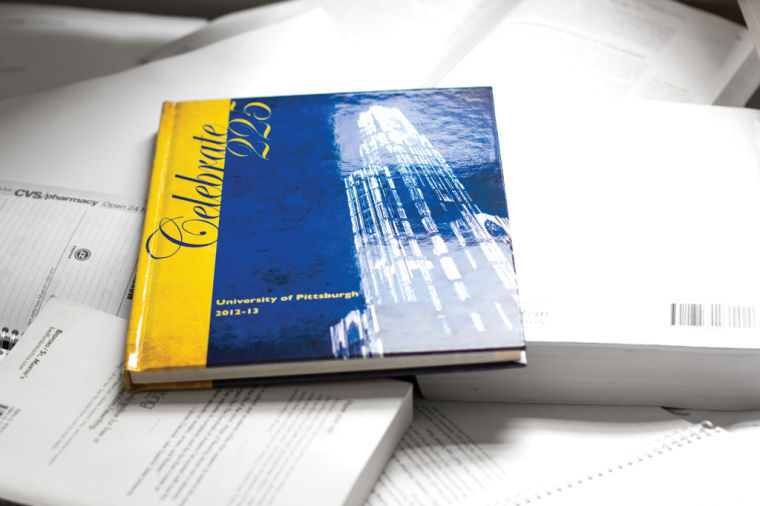

TreeRing produced the 2012-2013 edition of “Panther Prints,” and students had the option to upload digital photos to last year’s yearbook. But despite the expectation that this would be a big hit among students, it was poorly received.

Mina said that TreeRing has worked with schools in the past and helped stimulate an increase in yearbook sales as students gradually learned how to add their own content to the print edition. He thought that an abandonment of the digital form could be premature, having only had a year’s worth of data.

“One year with University of Pittsburgh is not enough data to understand [why students aren’t interested],” Mina said. “I would hate to see them leave completely, because I say it may be a bit early to give up on the effort.”

Ahearn said he could not speculate on how an additional year with TreeRing would impact sales.

New-age competition

Although interactive yearbooks can allow for more personal content, yearbooks still face the competition of social media.

Ahearn said the use of photo albums on social media sites has reduced the demand for yearbooks, but Brooks said the decline in interest occurred earlier.

Brooks advised the yearbook at the University of Oklahoma from 2004 to 2012. She said Oklahoma’s yearbook faced poor student interest during her time as associate director of student media, just as it had since the ’80s — before the surge of social media.

“The Internet did not kill college yearbooks,” Brooks said. “It just gave students a reason to say why they weren’t buying them.”

Shawn McFarland, who graduated from Pitt in 2005, said he knew about “Panther Prints” during his time as an undergraduate and considered joining the yearbook staff. But McFarland never bought a copy.

“At a school as big as Pitt, I figured I wouldn’t know 85 percent of the people in [the yearbook], anyway — so what was the point?” he said in an email.

McFarland said he thought that every University should offer a yearbook for those who do want a copy, but the decision to stop production does not upset him.

“At a major D-1 university, I feel like the reminisce factor really isn’t there in the future,” he said.

Vivek Sharma, a senior political science major, “had no idea that the yearbook existed.”

Sharma said that while he does not have an opinion on the death of the yearbook, it could have been better advertised to students when it was in circulation.

Ahearn defended his office’s advertising techniques.

“We were more aggressive in advertising last year than ever before, and that’s why we were so disappointed [at the sales],” Ahearn said.

He said the yearbook was promoted through emails and letters to students, flyers around campus and newspaper advertisements in The Pitt News and a University newsletter.

Ahearn said the advertising did increase the amount of students who knew about Panther Prints and came to the office to have a senior portrait taken.

In the 2011-2012 edition, there were 387 student portraits. In the 2012-2013 edition, there were 569 senior portraits, which marked a 47 percent increase.

The academic significance

Brooks and Satriano said that a yearbook is a historical record that reflects the culture of a time period, and, in older generations, it can be a treasured book of collegiate memories or a way to remember old classmates.

Brooks said genealogists and historians use yearbooks as research tools.

“If you are looking at an institution’s history, a yearbook shows what students did much more so than a newspaper because of the kind of stories it covers,” Brooks said.

Satriano said yearbooks record things such as the hairstyles and fashions of the times, as well as architectural changes over time. She added that a student who wanted to see what Forbes Field looked like before its destruction could consult yearbooks.

While the online photo album is supposed to play the same role, Satriano and Mina said a print yearbook has tangible value. While a physical book can sit immutable on a shelf for years, technology is constantly changing, and the online album may become obsolete.

Mina theorized the possibility of a new Facebook, or the lack of one at all, leading to the subsequent removal of uploaded photos and memories associated with them.

“How will you take them with you in a decade from now? What happens when you want to show your kids?” Mina asked. “How do you show them when those memories aren’t there?”

Satriano said that students will regret the change of media.

“Over time, students will say, ‘Gee whiz, I wish I had that yearbook, that picture, that hard memory that I can open and look at,’” Satriano said. “Unfortunately, the pictures they post to Instagram and Facebook will be gone. The yearbook lasts.”