Analysis: How a 1999 NATO operation turned Russia against the West

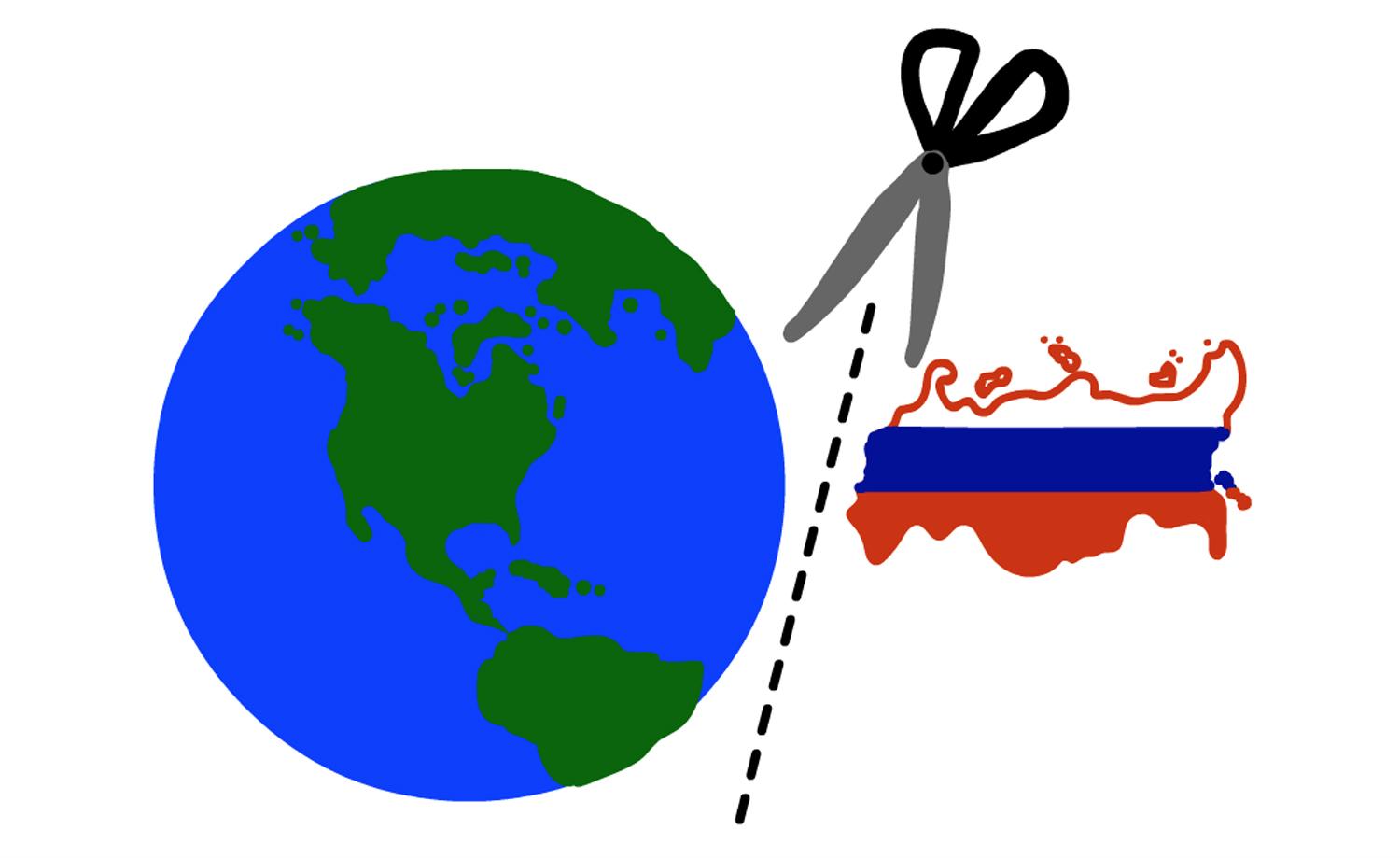

(Illustration by Elise Lavallee | Contributing Editor)

The name Boris Yeltsin should ring a bell, whether it brings to mind images of him leaping upon a tank during a coup in 1991 Moscow or standing drunk in his underpants in Washington, D.C. in 1995.

Yeltsin, the first president of the Russian Federation, may be remembered for his drinking habits, but he was a massively important political figure throughout the 1990s. Understanding Yeltsin is just the first step toward realizing that a 1999 North Atlantic Treaty Organization bombing of Yugoslavia served as the turning point in Russo-American relations and set the power of President Vladimir Putin against the United States.

But the story starts at the beginning of the decade. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union and final resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev in 1991, serious change swept across what is now the Russian Federation. Gorbachev, heralded in the West for helping to end the Cold War, experienced declining popularity at home while receiving praise from world leaders.

He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for helping to end the Cold War, while at home his approval rating dropped to 21 percent. In the final years of the Soviet Union, economic crisis struck the country, and the ruble reached historic lows by 1988. The post-Soviet ruble opened official trading at a rate of 1.8 rubles per dollar in 1991, and by the end of Gorbachev’s last year in power the value had plummeted, trading at a rate above 160 rubles per dollar.

Gorbachev was overthrown during a coup in August 1991, and Boris Yeltsin was elected president, a man whose commitment to Western economic radicalism would eventually be his demise.

In contrast to Gorbachev, Yeltsin was viewed by Soviets and Americans alike as a fresh face for the Russian Federation — and throughout the 1990s, he was. In fact, even by 1997 Russo-American relations were productive and cordial. Regarding his 11th meeting with President Clinton, President Yeltsin said, “[America and Russia] have a vast area of congruent interests. Chief among these is the stability in the international situation. We want to do away the past mistrust and animosity … We will have enough of both patience and decisiveness.”

So what happened? What led Russia to pass a new national security concept just three years later in 2000 that affirmed Russia’s commitment to dealing with “domination by developed Western countries?”

The answer lies in Yugoslavia. After World War II, six nations joined the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, or FRY — Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia. But Serbia, then-home to the autonomous province of Kosovo, became a battlefield of Russo-American relations.

Kosovo is one of two geographic homelands for Albanians, an ethnic group native to Albania and Kosovo that speaks Albanian and is Sunni Muslim in majority. A census in 1981 revealed that 77 percent of the population in Kosovo was Albanian, while only 13 percent was Serbian.

But the autonomous region was in Serbia, where the official language was Serbian and the official religion was Eastern Orthodox Christianity — 85 percent of the population were Serbs, and only 1 percent were Albanian.

Through the 1990s, this ethnic disparity escalated to all-out war — the Kosovo War began in March 1998, and ended on June 11, 1999. A group of rebels banded together as the Kosovo Liberation Army — or KLA — to fight against Yugoslavia for discriminating against Kosovo Albanians.

But things turned ugly in January of 1999. In the small town of Racak, Serbian security forces killed 45 Kosovo Albanians, and most of the slain were women and children.

In response to the Racak massacre, NATO did something unprecedented. The coalition wanted to end the massacres of Kosovo Albanians, but were told by Russian and Chinese UN delegates that their nations would oppose any use of force. So, without the authorization of the United Nations Security Council, NATO military forces launched a bombing campaign against Yugoslavia that lasted 78 days. Operation Allied Force — the official NATO code name for the attacks — resulted in the deaths of over 500 civilians.

When Russia was later ostracized by the Western world for its annexation of Crimea and actions in Syria, a journalist asked Putin if the decline of Russo-American relations was due to Crimea or Syria.

“You are mistaken,” Putin said. “Think about Yugoslavia. This is when it started.”

NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia represented a drastic use of military force that Putin saw as contrary to international law — which it probably was. And for people like Putin, who reminisce over the powerful Soviet Union that they grew up in, an attack on Serbia was an attack on a close ally.

So for the first few years of his presidency, during which he launched the nation into a new war in Chechnya, Putin focused on bringing dignity back to Russia. Even today, he’s still on this quest in places like Georgia, Chechnya and Crimea. Putin continues to reference Operation Allied Force when discussing international politics.

“Our Western partners, led by the United States of America, prefer not to be guided by international law … but by the rule of the gun,” he said in a 2014 speech defending his effort to annex Crimea. “They have come to believe … they can decide the destinies of the world. This happened in Yugoslavia; we remember 1999 very well.”

The wounds of 1999 still run deep, and Putin harnesses this Russian perception of American exceptionalism in order to play the victim card, turning his people against the West. In the same speech, Putin accused the West of lying to Russia, making decisions behind their backs and pursuing an “infamous policy of containment.”

Of course, this rhetoric works in a country where 88 percent of people get their news from primarily state-controlled television. Putin uses the media to convince his people of the West’s exceptionalism, but he doesn’t show the atrocities Russia commits to warrant political action like sanctions. This why his people don’t blame him for the declining price of the ruble or increasing food prices — they blame the Western world.

Understanding Putin’s vengeance against NATO —the United States included — for its bombing of Yugoslavia can provide a key lens into how Putin operates as a world leader. With him, things are personal — his quest to restore power to the Soviet Union is rooted in his feeling that the world turned against him and his people in 1999.

And as for solutions? There are few in sight. Even if you had the power to flip a switch and give the country the freedom of press, which has often served as the catalyst for revolutions, would you? Doing so could ignite a civil war and result in the deaths of millions — but the result might be a freer Eastern Europe.

If America truly is the nexus of democracy that the world perceives it to be, we must work on problems from their roots rather than attacking their victims. Bombing capital cities and starting proxy wars will get the world nowhere. Putin’s non-democratic expansion doesn’t follow the rules of political logic because much of it is rooted in a personal grudge — and understanding the cause of the grudge could prove vital in ending it.

Christian is the assistant opinions editor at The Pitt News. Write to Christian at cjs197@pitt.edu.

Recent Posts

‘He’s off to a much faster and better start’: Republicans reflect the second Trump administration’s first two months

Since Inauguration Day Trump’s second term has caused division amongst young Americans. Despite these controversies,…

Who Asked? // Why do we accept bad treatment from people?

This installment of Who Asked? by staff writer Brynn Murawski attempts to untangle the complicated…

What, Like It’s Hard? // Lean on your people

Contributing editor Livia LaMarca talks about leaning on your support networks and gives advice on…

Note to Self // Hot Girl Summer

In the sixth edition of Note to Self, Morgan Arlia talks about how she is…

A Good Hill to Die On // Down to Date and Time

In the latest version of “A Good Hill to Die On,” staff writer Sierra O’Neil…

‘Dress for Success: Closet to Career’ alleviates the stress of building a professional wardrobe

As the end of the spring semester rapidly approaches, many Pitt students find themselves in…