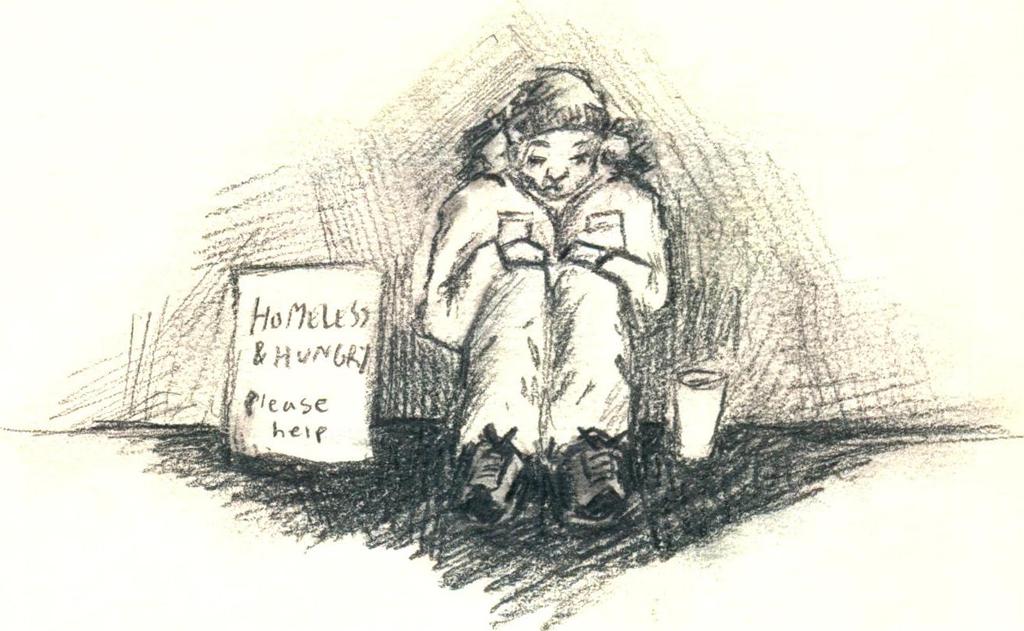

Annabelle Goll | Staff Illustrator

A lot of things have changed since the ’60s. Unfortunately, poverty levels in America isn’t one of them.

In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson launched what he called the War on Poverty. The goal of this initiative was bold and straightforward: The federal government would use all of its resources to, in the words of Johnson, cure and prevent poverty.

To achieve this goal, Congress rushed through several new programs designed to alleviate economic inequality.

This effort established major entitlement programs that still exist today. Food stamps dealt with hunger, while Medicare and Medicaid would provide health insurance. Combined with the programs of the New Deal, such as Social Security and Aid to Families with Dependent Children — more commonly known as welfare — the United States became a modern welfare state.

But the War on Poverty was, and continues to be, a dismal failure. The new safety net frequently traps the poor and prevents them from advancing.

While the poverty rate in 1973 fell to 11 percent — the lowest level since the federal government began measuring poverty in 1959 — this was the extent of the progress. Since 1973, the poverty rate has not fallen below 11 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau— in 2014, the rate was more than 14 percent.

Beginning in the late ’60s, the situation of poor communities has dramatically worsened in many respects.

In poor communities across the country the family structure has collapsed, employment has declined, schools continue to fail and the poverty cycle is as strong as ever.

Most people, including myself, agree that these are good and necessary programs in a country as prosperous as ours. But the issue is that these programs are so uncoordinated and disorganized they provide virtually no incentive to actually improve oneself when they can have the government pay for all of their needs.

One area where this effect is particularly apparent is the labor participation rate. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the 1964 male labor participation rate was about 80 percent. Today, it is more than 60 percent. Among working-age men, the participation rate has fallen from 97 percent in 1965 to only 88 percent in 2013.

The labor participation rate doesn’t tell the whole story, though. The War on Poverty has also caused exceedingly high part-time employment. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, only 3 percent of full-time workers lived below the poverty line in 2014 compared with 16 percent of part-time workers and 34 percent of non-workers. While there are several reasons for the growth of part-time work, welfare programs may be to blame.

Because most anti-poverty programs are means tested — recipients must fit specific qualifications to receive a benefit — a person making an amount that exceeds the qualifying level of income will be immediately and entirely cut off from benefits. When you factor in state entitlement programs this means that an individual can often make more by not working than by working for a salary that would cut off their benefits.

To help solve this problem, we must change the way we means test for basic entitlement, such as Food Stamps, welfare and Medicaid. By continuing to provide some degree of assistance beyond arbitrary income levels, we can reward entitlement recipients for working and provide them with a greater incentive to try to work their way out of poverty.

Another critical area of study is the family structure. Since the start of the War on Poverty, out-of-wedlock birth has skyrocketed from less than 10 percent in 1964 to 40.7 percent in 2012. About 37.1 percent of children grow up in a family headed by a single mother are poor, compared to only 6.8 percent of children born to a two-parent family. In other words, the chance of growing up in poverty is more than five times higher when the child is born out of wedlock.

With the family in tatters and the resulting general lack of support at home, the child living below the poverty line has to depend on the public education system for an avenue out of poverty. Unfortunately, the education system in poor areas of the country is an increasingly dismal failure.

The disparity between the quality of poor schools and their wealthier counterparts illuminates this problem. According to the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress report, only 24 percent of fourth graders who are eligible for a free lunch are proficient in math versus 59 percent proficiency among fourth graders who were not eligible. This means that the children who need the best education in order to break the cycle aren’t receiving enough attention.

But more money isn’t enough to solve the problem. Between 1970 and 2005, average per-pupil spending more than doubled from $4,060 to $9,266 while test scores remained virtually unchanged. A more productive solution lays in charter schools, which don’t host the bureaucratic inefficiencies that come with public schools and teachers unions.

According to the Center for Research on Education Outcomes, urban charter schools have been successful in producing major achievement gains for students eligible for subsidized lunches and low baseline scores as well as increased math and reading scores for everyone except white students.

If we want to solve the poverty trap, we must accept that our efforts have so far served only to perpetuate poverty and disincentivize progress. There is, however, some good news. In 1996, after years of failed attempts at reform, Congress added a work requirement to welfare. The results were stunning: Within a decade the number of Americans enrolled in welfare had fallen by half.

Just as importantly, poverty fell dramatically among households headed by a single mother, which traditionally have been the most vulnerable to poverty. In 1991, a whopping 55.4 percent of children in these households were in poverty. By 2001 that number had declined to 39.3 percent.

But welfare reform was only a critical first step. Other programs are still steadily expanding, and much more is needed if the entitlement trap is to be eliminated.

In his 1935 message to Congress, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said dependence on relief induces a spiritual and moral disintegration that foretells a destruction of our country’s fibre. The only way to combat this disintegration is for the able bodied but destitute to work. We would do well to take F.D.R.’s advice today.

After 50 years of crippling the progress of America’s poor, we must take a different approach. If we want to solve this problem we ought to take Johnson’s original advice and offer the poor “a hand up, not a hand out.”

We must create an incentive to succeed, not an incentive to fail.

Email Arnaud at awa8@gmail.com

Recent Posts

‘He’s off to a much faster and better start’: Republicans reflect the second Trump administration’s first two months

Since Inauguration Day Trump’s second term has caused division amongst young Americans. Despite these controversies,…

Who Asked? // Why do we accept bad treatment from people?

This installment of Who Asked? by staff writer Brynn Murawski attempts to untangle the complicated…

What, Like It’s Hard? // Lean on your people

Contributing editor Livia LaMarca talks about leaning on your support networks and gives advice on…

Note to Self // Hot Girl Summer

In the sixth edition of Note to Self, Morgan Arlia talks about how she is…

A Good Hill to Die On // Down to Date and Time

In the latest version of “A Good Hill to Die On,” staff writer Sierra O’Neil…

‘Dress for Success: Closet to Career’ alleviates the stress of building a professional wardrobe

As the end of the spring semester rapidly approaches, many Pitt students find themselves in…