Pitt to study Alzheimer’s outside of the brain

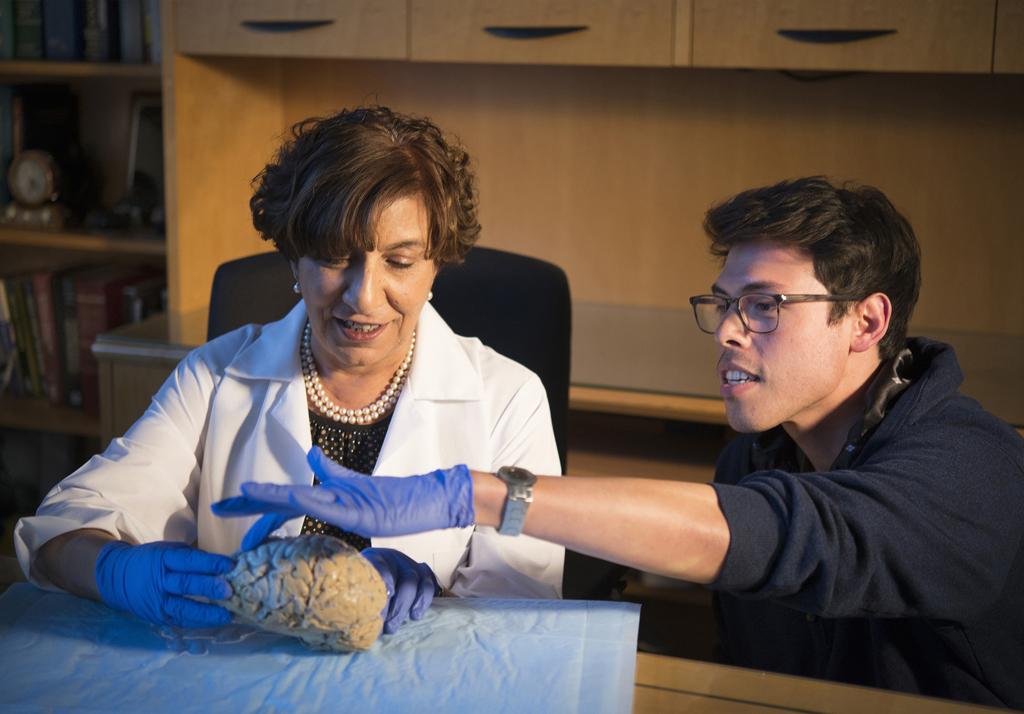

Dr. Claudia Kawas, who oversees The 90+ Study, and Ryan Bohannan, staff research associate, examine the brain of a normal 74-year-old woman at UCI. "We've got to find a cure (for dementia and Alzheimer's disease)" Kawas, geriatric neurologist and co-principal investigator, says. (Cindy Yamanaka/Orange County Register/TNS)

By examining protein structures, Pitt researcher Rena Robinson aims to shift the focus of Alzheimer’s research from the brain to the body.

The National Institutes of Health recently granted Robinson $1.7 million over the next five years to study proteins affected by Alzheimer’s disease outside of the central nervous system. The lab at Pitt will use mice to study disease progression in peripheral organs, such as the liver, heart, kidney and lungs.

Researchers in Robinson’s lab will track changes in the proteins of the body as the disease progresses through various organs to see if they relate to changes in the brain and spinal cord.

The premise of the proposal is “to better understand what happens outside of the brain in a neurodegenerative disorder,” Robinson said. “The community knows a lot about the pathology and what takes place in the brain, but more recently, we’re learning that other systems are important in how the disease develops.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, five million Americans were living with the disease in 2013. If scientists fail to find a cure by 2050, the CDC expects that number to triple.

Robinson said most Alzheimer’s research so far has focused solely on the disease’s impact on the brain, rather than the other vital systems in the body.

Proteomics, the study of proteins’ structure and function, is key to Robinson’s research because it shows how proteins interact with the body.

“This will be the first demonstration of using proteomics techniques to look at what’s happening to multiple body systems at the same time during Alzheimer’s disease,” Robinson said. Looking at proteomics, the study will examine Alzheimer’s impact on biological pathways, such as energy metabolism, as the disease progresses. Through protein studies, the lab can look at multiple pathways at once.

Robinson worked with proteomics in her postdoctoral program in Allan Butterfield’s lab. Butterfield, a professor at the University of Kentucky, oversaw Robinson’s work with mice with mutated proteins. There, Robinson substituted an amino acid in a mutated protein and saw positive changes in the mouse, such as less oxidative stress, which prevents a cell from detoxifying free radicals in the body.

Butterfield’s lab was one of the first to use the technique of redox proteomics, a process that allows researchers to identify proteins with oxidative damage. After publishing a comprehensive report on the technique in 2012, Robinson learned the technique and expanded her own knowledge of proteomics.

“There are a number of labs who use proteomics, but compared to genomics it’s a rather small set of people who do that,” Butterfield said. “It’s a very instrument-rich technique, it requires a good deal of expertise in instrumentation and protein separation and informatics.”

Robinson’s lab can get up to 24 samples in a single analysis, whereas a traditional lab can get up to 12. The higher sample size means the study’s results are likely to be more precise. The lab said its goal throughout the study is to get up to 60 samples from a single analysis.

Oscar Lopez, University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer Disease Research Center director, said Robinson’s undertaking will reward the field with new insight on proteins in the aging body.

“If you can detect a pattern of abnormal proteins, then that would help people to improve diagnoses and help to predict what is going to happen to normal people who do not have the disease but who have that abnormal protein,” Lopez said.

From the onset of the disease, Butterfield said a patient has roughly eight to 10 years to live, and Alzheimer’s research aims to extend that lifespan.

“The most activity in Alzheimer’s disease research is aimed at trying to slow the progression by therapeutic intervention, with mixed results,” Butterfield said.

Having worked with Alzheimer’s disease since she finished her doctorate program and witnessed its impact firsthand, Robinson said she wants to make progress that’ll change the way researchers study Alzheimer’s.

“The urgency at which we need to understand and come up with treatments for Alzheimer’s is really high,” Robinson said. “It’s important in this field to explore areas we haven’t explored before and try to get a handle on this disease.”

Recent Posts

SGB addresses concerns about ICE presence on campus, hears SJP lawsuit against administration, approves governing code bill

At its weekly meeting on Tuesday at Nordy’s Place, Student Government Board heard concerns about…

ACLU of Pennsylvania sues Pitt over SJP suspension

The ACLU of Pennsylvania filed a federal civil lawsuit against the University of Pittsburgh and…

Marquan Pope: The ultimate shark

One of the most remarkable things about sharks is that an injury doesn’t deter them.…

Who Asked? // Do we really get a summer vacation?

This installment of Who Asked? by staff writer Brynn Murawski mourns the seemingly impossible perfect…

Notes From an Average Girl // Notes from my junior year

In this edition of Notes From an Average Girl, senior staff writer Madeline Milchman reflects…

Meaning at the Movies // The Power of the Movie Theater

In this edition of “Meaning at the Movies,” staff writer Lauren Deaton discusses her love…