Going Virtual

Shawn Jackson, a senior computer science major, works as a student employee at the Teaching Center. For his first VR experience, he used Star Chart, a constellation simulation. Elaina Zachos | Visual Editor

Michael Arenth reached for his goggles, strapped them to his head with a rubber band and embarked on a trip 6,000 miles away.

He sat in the back of a bumpy brown canoe and watched the bony arms of a 9-year-old refugee paddle across a swamp, enveloped by the emerald-colored fields of South Sudan.

With clouds looming overhead and birds chirping around them, the two escaped from fighters who invaded the boy’s village in “The Displaced,” the New York Times’ online virtual reality experience that profiled victims of the refugee crisis.

“To me, that was when…a broader audience and a different application for [virtual reality] became more mainstream,” Arenth said of his visual adventure. “And I think that’s when I felt like, ‘Boy, we need to be sure we’re on top of this.’”

Arenth got Google Cardboard with his Sunday New York Times subscription in November, 2015. The device is a $15 virtual reality headset made of cardboard and a 45mm lens, with a slot to put a smartphone capable of streaming 360 video. He, and more than 5 million others who have purchased Google’s headset since then, saw virtual reality as a marvel, not a gimmick. After virtually visiting Ukraine, South Sudan and Lebanon in “The Displaced,” Arenth finally understood how the technology could have applications past roller coaster simulators and horror games.

As the director of classroom and media services for Pitt’s University Center for Teaching and Learning, Arenth thought about how he could implement virtual reality in classrooms on campus — an anthropology course visiting ancient ruins, a chemistry class viewing 3-D models of a compound’s molecular structure, geology students surveying a disaster site. Following his work since then, he says that students are only 18 months away from seeing a virtual reality component on a syllabus.

“We are excited about the possibilities that we haven’t even thought of yet,” Arenth said.

Arenth isn’t the only one who’s seen capabilities for virtual reality technology outside of entertainment. Doctors are using headsets to view 3-D models of their patients’ organs, engineers are building games to make life easier for people with disabilities and educational organizations are thinking of ways to bring immersive experiences into the classroom — and all of that work seems to be converging in Pittsburgh.

At Pitt, several faculty members and researchers see virtual reality’s potential to change everything from how professors teach their students to how surgeons prepare for the operating table. But the industry, poised to make huge leaps in the next five years, may not take hold in Pittsburgh unless Pitt researchers can convince investors that their projects are worth it.

According to Lorin Grieve, a professor who teaches in Pitt’s School of Information Sciences and the pharmacy school, it takes tons of time and money to create quality virtual reality experiences.

Most commercially available virtual reality headsets are expensive, from the $599 Oculus Rift to the $799 HTC Vive, plus making games means hiring entire development teams to spend months, even years, building something that can go to market. And even if investors were willing to pour cash into efforts with the technology, there’s no science to prove that virtual immersion helps students learn better.

“A lot of people who aren’t interested in VR — a lot of people who are maybe older, more traditional in their outlook are saying, ‘Well, show me that it works,’” Grieve said. “And we just haven’t been able to do that yet.”

Surgeries, spaceships and subways

In the basement of Pitt’s Information Sciences Building, Grieve works with information sciences professor Dmitriy Babichenko on various virtual and augmented reality projects.

The walls are blank and there’s a stray coffee mug for every gadget in the room — from a 3-D printer buzzing in the corner to two computer monitors on the far end. Babichenko is discussing the future of virtual reality when Grieve leans over and asks why most people buy Blu-rays instead of HD DVDs.

“Because the porn industry took up Blu-ray and not HD DVD,” Grieve said. “Historically, the porn industry has a very heavy say in what works commercially, as far as products are concerned.”

It’s a joke, but not really. According to a Business Insider article published in August, the total revenue from virtual and augmented reality — lately catchall terms for anything that creates a panoramic, realistic environment, from 360 video to wearing sensor-rigged accessories like helmets or gloves — is projected to increase from $5.2 billion in 2016 to more than over $163 billion in 2020, making it one of the fastest-growing entertainment products.

This covers pornography as well as gaming — PlayStation’s virtual reality headset has slowly added games since it released Oct. 13. Virtual reality has cropped up in television, too — NBC partnered with AltspaceVR to stream the second presidential debate in virtual reality, while the NBA plans to start broadcasting a game a week in 360 video. The New York Times still produces virtual reality experiences, and the technology has even made its way into health care.

This past January, doctors at a Miami hospital saved a baby’s life after consulting Pitt’s David Ezon, who used an app called Sketchfab to view the patient’s heart in 3-D.

Take the project Babichenko is working on. Through EngagePitt, the University’s crowdfunding platform, Babichenko raised $5,842 over the summer for ScopingSim, a virtual reality game that would allow nurses to practice performing endoscopies, colonoscopies and bronchoscopies, procedures to look into a patient’s digestive tract, large intestine and throat, respectively.

Instead of practicing on a mannequin model, which can cost anywhere from $3,000 to $50,000, students would practice the procedures using endoscope models with built-in sensors that would buzz or ring when someone makes a mistake — much like a high-tech game of “Operation.”

“They actually have to learn how to navigate airways,” Babichenko said. “You have a subway tunnel or corridors on an alien’s ship. And you’re being chased by an alien, or chasing an alien and you have to move the scope quickly, but precisely to escape or catch [it] in first-person shooter view.”

Next semester, Babichenko will teach a special topics course in programming and game design where students will have the chance to work on ScopingSim for credit — a way around the estimated $200,000 price tag ScopingSim would take to make in its entirety, development team and all. The funds raised through EngagePitt will pay for equipment, including development kits for the virtual reality headsets, as well as materials to build the scoping sensors.

But Grieve, when talking separately about virtual reality’s potential educational role, noted another possibility: Virtual reality helps a classroom in a way a traditional lecture style could not — engaging students by streaming a drone’s view of Chernobyl, for instance, instead of reading about the nuclear disaster in a book — but the necessary resources may be more expensive than practical.

“It’s the kind of thing where we have to look and say, ‘Is it worth it?’” Grieve said.

Meet CAREN

About three miles east of Oakland in Bakery Square, CAREN wakes up. She steals whatever power nearby Google Pittsburgh isn’t using, then begins whirring, roaring, illuminating.

After a few minutes, she quiets into a low hum. She’s ready.

Computer Assisted Rehabilitation Environment — CAREN — is a 3-D simulation owned by Pitt and the Veteran Affairs’ Human Engineering Research Laboratories, or HERL. CAREN is set up about six feet off the ground. Users stand on a platform that looks like a concert stage, only in front of a large projection screen, a hydraulic lift and two treadmill pumps on top.

It’s used by HERL — a facility dedicated to improving the quality of life for people with disabilities – to study the gait of people who use prosthetics and to analyze how wheelchair users operate and propel in different environments. HERL does this by projecting virtual reality experiences on the screen — like a speedboat racing simulation — to help users with disabilities get accustomed to a new wheelchair or prosthetic limb.

According to Deepan Kamaraj, a research associate who works primarily on HERL’s virtual reality projects, the few wheelchair users who are lucky enough to try CAREN want to know when they can take something like the simulator home.

“That’s what we’re trying to address by using virtual reality,” Kamaraj said. “How much of the training that we would like to do — can it be started in the hospital and continued over time? So you’re not only giving prolonged support, now you’re providing support in their home, where they would eventually want to be functional.”

The first prototype of CAREN — one of only a handful of its kind in the country — was created by Netherlands’ Motek Entertainment in 1998. The simulator costs up to $1.5 million, so in-home support is a long way off. But HERL’s work with CAREN isn’t its only ongoing project.

On one side of HERL’s wheelchair testing space — which looks more YMCA than laboratory, with a basketball hoop, kitchen and a small weight room — is a propulsion runway and wheelchairs rigged with motion capture sensors. The sensors are similar to what Hollywood visual effects artists use to allow an actor like Mark Ruffalo to perform as the Hulk, importing his movements and facial expressions to map onto the computer-generated green monster.

But instead of making superhero movie magic, Kamaraj is developing a virtual reality game that would help new wheelchair users learn to avoid obstacles and maneuver crowded environments. By putting motion capture sensors on wheelchairs and the people driving them, Kamaraj can figure out if someone is moving the chair at the right angle and speeds — both factors that, if done wrong, could lead to someone tearing a muscle, or breaking a wheel on a curb.

Kamaraj is working to make the game compatible with the Oculus Rift, which is on the higher end of headsets in both quality and price, so he can build realistic virtual models of the chairs. This might help new users improve the efficiency and safety of their driving in a virtual space before moving to the real thing — before they even leave the hospital.

“So if you have an Oculus-based game, maybe they’re not completely in a situation that they can get into a chair and start being mobile and move around,” he said. “But if you provide them an opportunity to get training way before they do that, they get better accustomed to mobility once they’re out of the hospital.”

He added that the inflation of health care costs makes a cheap, in-home rehabilitation option almost necessary — if someone has a stroke and can’t walk, for instance, the person doesn’t have to spend time and money in a hospital going to therapy every day.

“The insurance reimbursement policies, they’re shrinking the time more and more,” he said. “So post-stroke, about 10 years, maybe 25 years ago, you could be in the hospital for anywhere from three to six months, you would get continued physical therapy and [occupational] therapy care. But now, you get three weeks at the max. And then they’re like, ‘Well, you gotta go, that’s it.’”

Egypt, Rome, Mexico and Beyond

If Egyptian pyramids ever closed to the public for preservation, 20-foot-tall pharaohs could dwarf every student inside a $15 headset.

You could recreate just about any lost artifact — visit the Colosseum before earthquake damage, feel the true scale of the Mayan Empire, even take a tour of Forbes Field and watch Sweetness run the bases one last time.

Arenth, Meagan Koleck and Cynthia Golden from Pitt’s Teaching Center could go on for days. They’ve followed along with developments in the virtual reality industry in hopes that Pitt will be ready if the technology finds commercial success.

With the funds Pitt allots the center to invest in emerging technology, Arenth and company bought an Oculus Rift, as well as sent Koleck, a media specialist for the center, to conventions like October’s WEIRD REALITY symposium at Carnegie Mellon University, which featured several virtual reality projects.

The goal is to learn if immersion actually helps students learn better than a textbook or traditional lecture, then Pitt would know if students could benefit from owning something like a Google Cardboard.

At other schools, students already are putting it to use. Boise State University students used Oculus Rift headsets to learn catheter insertion procedures and engineers from Penn State University assembled virtual pieces of a coffeemaker more efficiently using an Oculus Rift than a desktop computer program.

The New Media Consortium, an association of more than over 250 colleges, museums and corporations across the world dedicated to finding new technologies, listed both of these programs in its 2016 Horizon report under “Important Developments in Educational Technology for Higher Education.”

“Early pilot findings indicate positive impacts on the classroom, including enhanced group dynamics and peer-to-peer learning,” the report reads, citing several case studies that showed the benefits of virtual reality in learning.

Maybe Pitt’s Teaching Center will make the 2017 report, as it’s now imagining an immersion therapy experience for public speaking, where a student would practice speaking to an auditorium full of actors from the theatre arts program. The center has also spoken with the studio arts department about creating art in a virtual world, then printing it out on a 3-D printer.

“We invest some time, which is people, resources and some dollars into acquiring some cameras, because we have to be on the edge a little bit,” said Golden, director of the center.

In addition to its own early investigation into the technology, the center has kept its eye on its neighbors, CMU and Facebook-owned Oculus, the latter of which opened a research office in Oakland earlier this year. The center has met with CMU technology experts and says it’s open to collaboration opportunities with Oculus once it gets settled on campus.

CMU is home to Jesse Schell, a professor whose nationally known game design company, Schell Games, just released “I Expect You To Die,” a virtual reality puzzle experience where the user plays as a spy trying to escape a mysterious room.

Though we might not be living in the cliched 21st century sci-fi movie we once envisioned, faraway worlds, from war-torn Sudan to a failing human heart, can now be explored through the lens of a $15 piece of cardboard. But modern miracles don’t mean much if they’re kept in labs and tech conventions. Virtual reality is almost in the classroom, but for now, students are still bound to L-shaped desks, staring at sketches of the human anatomy, viewing Renaissance art on Powerpoint slides and watching red-faced classmates give their first presentations.

“Our world has changed, technology has changed and we’ll probably have to start looking at how we’re teaching students in a way that works for students who are already born in the 21st century,” Koleck said. “So investing in something that could fail is a lot of times worth the risk.”

Recent Posts

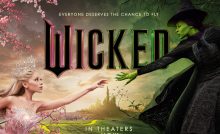

Defying expectations and gravity: Why I’m holding space for the new ‘Wicked’ movie

Elphaba’s battle cry at the end of a Target commercial, Ariana Grande clutching Cynthia Erivo’s…

Opinion | Failing your New Year’s resolution is better than not making one

Let’s get used to failure — let’s fail over and over and over until it’s…

Chancellor and Provost office to take control of local antisemitism initiative

President of the Faculty Assembly Robin Kear announced on Dec. 4 the ad hoc committee…

Pitt football loses 6OT bowl-game thriller, retains crucial players over the holiday break

Pitt football closed out its 2024 season over the holiday break with a 46-48 loss…

Pitt men’s basketball stays hot over winter break, conquering California ACC newcomers

The new year is a time for change. Most people lay out resolutions while striving…

Photos: Pitt men’s basketball dominates Stanford

Pitt men’s basketball advanced to 3-0 in ACC play with an 83-68 domination over Stanford…