Opinion | Dealing with information overload

October 2, 2019

One of my least favorite places to visit is Times Square in New York City. Growing up, I adored hopping on the two-hour train to see a Broadway show or dine in some of the country’s most iconic restaurants. But on my recent trips, I’ve found that there is nowhere to breathe. That single square mile is flooded with hundreds of thousands of people, and that’s just on an average Tuesday afternoon. The stores are too crowded, the wait times are too long and walking on the sidewalk is too much like a stampede of wild horses.

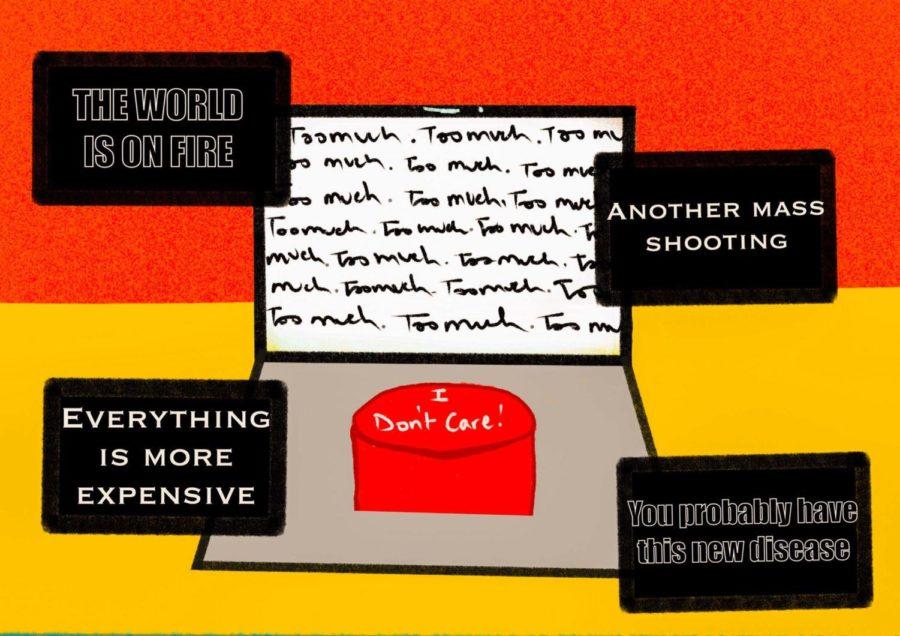

While I no longer venture to Times Square, I find that this same feeling of inescapable chaos has permeated so many other parts of my life. We have the ability to connect with even more people than those in Times Square by simply turning on our cell phones. Every day, we are bombarded with incessant tweets, texts, news articles and other programming, and much like when walking around the Big Apple, we have little room to breathe.

On a societal level, we are facing extreme “information overload,” a term popularized by author and futurist Alvin Toffler in his 1970 book “Future Shock.” According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the term refers to “a situation in which you receive too much information at one time and cannot think about it in a clear way.” It has massive consequences, on both micro and macro levels, and in order to address rampant political division, environmental crises and other perils plaguing our world, we must first consider the ways in which we consume and respond to information.

Toffler explains information overload through the example of World War II soldiers, many of whom actually fell asleep on the battlefield as machine guns rapidly fired bullets their way. It was not due to a lack of sleep or other physical conditions, but the incessant stimuli actually overwhelmed some men so much, their bodies saw sleep as the only natural response. For those who remained awake, the incredible amount of overpowering stress triggered hypersensitivity, causing many to become easily angered and extremely anxious or even apathetic.

Off the battlefield, we see parallels between the manner in which soldiers responded to stress and the ways in which we process news around us. Like bullets, headlines are flying at us at higher rates than ever before, in more ways than ever before.

Everywhere we turn, we face the inescapable demand to absorb information. Each morning, I wake up to a notification from The New York Times with the day’s “top stories,” and there are usually upwards of five or six full length articles. My Twitter notifications alert me about impeachment hearings, environmental crises, celebrity scandals and other situations that bring me immense stress.

According to The Atlantic, four of the top news organizations — The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and Buzzfeed — combine for a total of about 1,192 stories and videos published each day. That’s nearly 1,200 tidbits of info that, in order to be civically engaged and in-the-know citizens, we’re expected to navigate.

As I’m writing this, more than 200 billion tweets have been sent this year. Facebook has over 2.41 billion monthly active users, uploading about 300 million photos per day. A 2015 study from the Pew Research Center found that the number of people using Facebook and Twitter as news sources has increased. Our social networking platforms never stop and have increasingly metamorphosed from ways to connect with loved ones to additional spaces in which news is shared and absorbed.

Daniel Levitin, an author and psychologist at McGill University, claims that in general, there is more information from the last decade than in all of history prior.

“I’ve read estimates there were 30 exabytes of information 10 years ago and today, there’s 300 exabytes [one billion gigabytes] of information,” he said.

This trend seems harmless, even positive. There are more ways than ever to stay in touch with the important things happening in our world — and there are a lot of important things. The problem is not increased access to information, but a decrease in ways we can take a break from it.

Our brains are designed to multitask. We can handle three, maybe even four stimuli at once. But in order to sift through immense amounts of information, we are asking ourselves to process much more than that.

According to a 2002 brief from Joseph Ruff of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, information overload has resulted in Information Fatigue Syndrome, a term coined by mental health practitioners to describe poor concentration, pervasive hostility, trance-like states brought on by habituation — in which the brain temporarily shuts down from over stimulation — and hurry sickness, the belief that one must keep up with the pace of time.

In a sample of business managers, they found that 33% felt the need to be constantly informed resulted in ill health, 66% said that information overload increased hostility with their coworkers and made work less rewarding and 62% reported that it has adverse effects on their social and personal relationships. Information overload impacts more of us than just those diagnosed with IFS, as everyday people see this phenomenon reaping havoc on their relationships, careers and even their physical health.

It is imperative that we learn to find a balance between being engaged with the world around us and avoiding IFS. And surprisingly, doing this is a lot more simple than you may think.

Every night, take two minutes to do what productivity specialist David Allen calls a “brain dump.” Before getting to bed, write down all the thoughts still whirling around in your mind. Dump these news stories you can’t forget about and other pestering thoughts in a journal and leave them behind. Make room for new thoughts or for relaxation.

Next, ditch the phone when its not time to be productive. Admittedly, this one is hard and is something I continue to struggle with. Research shows that having your phone, a device used for productivity and engagement, in your place of rest and respite has negative effects on your mental health and sleep patterns. When it’s time to hit the hay, leave the phone on your desk and read to fall asleep instead. When you have downtime during the day, try journaling, playing music or going for a run instead of sitting on the couch engrossed in Instagram.

So, yes, keep up to date with the important things happening in our world — by, for example, subscribing to The Pitt News — but take the time to ready yourself to absorb, process and act upon information first. Occasionally unplugging is not being uninformed, but is a necessary precaution to protect your mental health.