Opinion | Personal essays are never just personal

November 6, 2019

Pitt’s campus was screaming and burning Monday night, and it had nothing to do with a dumpster fire outside of Posvar this time.

Writer Leslie Jamison paid Pitt a visit on the last stop of the tour for her new collection of essays — “Make It Scream, Make It Burn.” She live-taped an interview for the Longform podcast, talking about the creation of her new book. Critics often refer to her as the writer who brought forth a new definition of the essay — though it’s hard to redefine something that most people didn’t really understand in the first place.

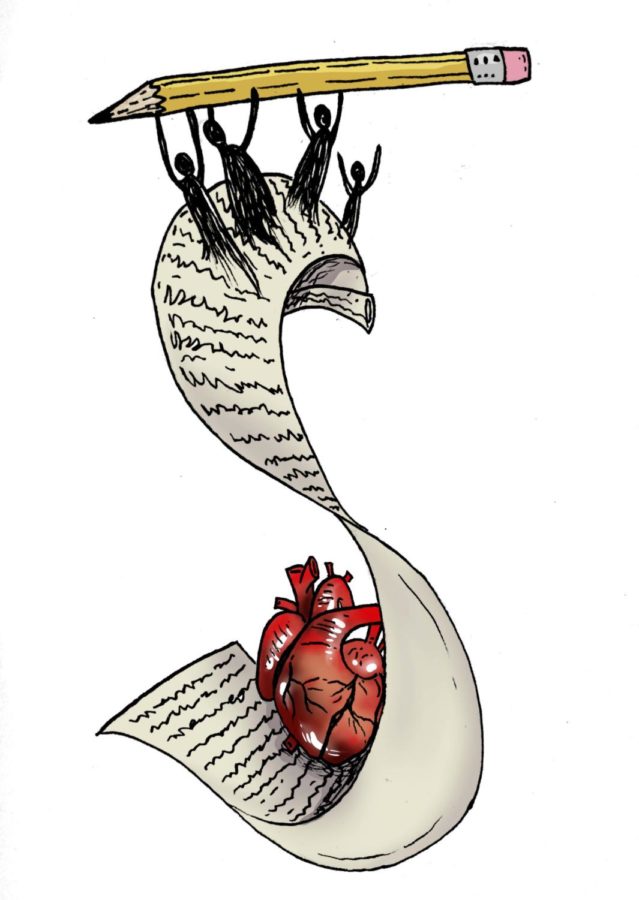

Personal essays conjure shuddering images and bad feelings for most of us — writing the Common Application essay senior year of high school about “overcoming a hardship,” or perhaps the middle school essay about why skiing over Christmas break is just so much fun. “So you just write about yourself?” is the question I most often hear when I talk about creative nonfiction. And maybe writers of this genre do write about themselves, to some extent. But creative nonfiction is about looking squarely at the world and subsequently looking inside yourself, to find something that will help explain an interpretation of both life and the world. Like all art, creative nonfiction is never about a singular element. Even the personal essay isn’t personal.

“When I deploy myself on the page, I’m always asking some sort of question,” Jamison said. “Writing about myself is an effort to make meaning out of something bigger. It’s never really just a story about myself … it’s a meditation, a tethered presence in a vast thing.”

The genre of creative nonfiction is what writer Lee Gutkind defines as “true stories well told.” It’s a broad definition, though that’s quite fitting, since essays are oceanic entities. Jamison’s work exemplifies the idea that creative nonfiction has no boundaries. In her new book, she writes an essay about the loneliest whale in the world, using the obsessions of others to tell the story, rather than her own obsessions. She ends the collection on a deeply personal note, with an essay about pregnancy and childbirth in the aftermath of an eating disorder.

However, even this essay was largely about the idea of one seeing ghosts of their past selves and a story about finding oneself in an experience. In Jamison’s case, this experience was pregnancy and childbirth, though it’s different for all writers and for all essays.

Another writer who uses the personal essay to ask larger questions about the world is Margo Jefferson, as in her essay “Scenes From a Life in Negroland.” The essay is a series of vignettes about growing up in a middle-class black family — what she refers to as “the third race.” But the essay is really asking questions about the difference between black and white privilege and the intersections between race and wealth. Essays aren’t statements or answers as much as they are pieces of writing asking discrete questions — this is something Jamison also touched on Monday night.

If we limit essays by defining them as writing that is entirely personal, then we are missing the point — and we’re missing a chance to find a new horizon of knowledge, too. Essays tackle questions that are unanswerable and seek to answer them anyway. What we get when we read the essay isn’t the answer, but the search for the answer. Even more so than fiction perhaps, essays articulate the honesty in the human journey, the idea that most things don’t really have a definitive ending. Essays also look at life as a continuation, rather than a story with a beginning, middle and end.

“In a way, this book is just a continuation of the first essay collection,” Jamison said, referencing her 2014 book, “The Empathy Exams.” “In a lot of ways, it’s asking the same questions and searching for the same answers. Now, by a woman in her 30s instead of her 20s, a woman who has grown and sees the world differently. But writing — my writing — is always a continuation.”

The title essay of the collection sums up what it means to be an essayist quite well. In “Make It Scream, Make It Burn,” she writes about the job of the writer, which is to take a normal element of life, something one might walk past everyday, and bring it to life — to make it scream, and make it burn. And in order to make something scream and burn, a writer can’t just write about it from their perspective — they can’t write an essay that is just personal. The writer has to look at the world outside of themself first, and then perhaps, look inward and incorporate themself into the essay.

“The quest to keep speaking, the inability to ever say enough,” Jamison writes of art, in “Make It Scream, Make It Burn.”

This is what an essay is. Not a singular faceted story about oneself or a pleading for pity, but a piece of art that reaches for something that the writer looks at and wants the world to see. It’s an attempt to grasp a concept that is largely ungraspable. The essay knows this, the essay acknowledges this. The essay keeps reaching for the unreachable thing anyway.

Leah Mensch is the opinions editor. She writes about reading, mental health and the spices of the world for The Pitt News. Write to Leah at [email protected].