‘You’re just in awe’: Spectators reminisce on Kobe’s Pitt visit

The Fitzgerald Field House, once home to the Pitt basketball teams, hosted a 17-year-old Kobe Bryant in a dunk contest that preceded the 1996 McDonald’s All-American Game.

January 30, 2020

Pittsburgh isn’t typically considered a basketball city. Despite proudly hosting an NHL, MLB and NFL franchise, no professional basketball team has called the City its home in nearly 50 years.

But for one chilly weekend in March 1996, Pittsburgh became the national focus of the basketball community, hosting the 19th annual McDonald’s All-American game. The main attraction was a skinny, charismatic 17-year-old high school senior from the Philadelphia suburbs named Kobe Bean Bryant.

The sports world has been in mourning since early Sunday, when a helicopter carrying Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter Gianna and seven other people suffered a fatal and tragic crash in Calabasas, California.

As people shared images and told stories of Bryant’s life, footage from that weekend in 1996 began to spread on Twitter. The clips served as a chance for many in the Pittsburgh area to recall the unforgettable memories made that weekend more than 23 years ago.

The event kicked off with slam dunk and 3-point contests at Pitt’s Fitzgerald Field House on Saturday, before playing the All-Star game the next day in the Civic Arena, the Pittsburgh Penguins’ home at the time. Bryant participated in both the dunk contest and game.

Some may recall Kobe Bryant coming to Pittsburgh in 1996 as a high school senior to play in the McDonald’s All-American Game at the Civic Arena and compete in the Slam Dunk Contest at Fitzgerald Field House. Here are a few shots from our archives. pic.twitter.com/Zyk0qP4WQn

— Ryan Recker (@RyanRecker) January 26, 2020

Vic Laurenza Jr., a father who lives in Cheswick, attended both nights of action as a junior in high school with his own father. A basketball player himself, he couldn’t wait to catch the action. Though the details remain a distant memory, he remembers Bryant being the headliner.

“He was the player everybody came to see,” Laurenza said.

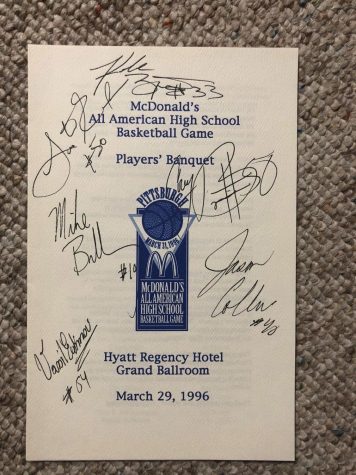

A program for the 19th annual McDonald’s All-American Game is signed by Kobe Bryant, No. 33, at the top.

Mike Kovak, now a copy editor for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review’s sports department, originally covered the weekend’s events for The Pitt News. As the sports editor in 1996, Kovak couldn’t pass up the chance to cover the event.

“Since I was the guy in charge [of the sports section],” Kovak said. “I probably was like, ‘Well I’m doing this because I wanna see Kobe Bryant.’’’

Just a week before the Pittsburgh event, the 6-foot-6 phenom led Lower Merion High School to the PIAA AAAA state championship, its first in program history. In his junior season, Bryant averaged 31.1 points, 10.4 rebounds and 5.4 assists per game.

A couple months later, like a normal senior, he attended his high school prom. His date? The superstar singer/songwriter Brandy.

“If you followed sports in 1996, particularly basketball, you knew who Kobe Bryant was even though he was in high school,” Kovak said. “Especially in Pennsylvania.”

The dunk contest featured a supreme lineup of Bryant, Tim Thomas, Lester Earl and Corey Benjamin. All four put on a show at the Field House, which at the time served as the home of Pitt basketball.

Bryant got the crowd on its feet with a left-handed windmill jam in the early rounds. After missing a few of his next attempts, he settled with a still-impressive reverse double-clutch slam.

Though Bryant had the crowd going wild, it was Earl who eventually took home the crown. He amazed the fans with multiple creative dunks, including one where he leapt over a ball rack.

The next day, fans flocked to Civic Arena for the main event. The East and West sported rosters stacked with future NBA stars including Jermaine O’Neal, Mike Bibby, Stephen Jackson and Richard Hamilton. Still, Bryant’s name shined over all of them.

“Kobe was the marquee guy,” Kovak said. “He was the reason why everything was packed — why the dunk contest had a big crowd and why the Civic Arena was at capacity for that game.”

Everyone wanted to see the future of the sport in the building that night. Lawrence Muir, who still often goes to Pitt basketball games at the Petersen Events Center, attended the game as a high schooler before playing basketball at Washington and Jefferson College. He recalls seeing letterman jackets throughout the stands as varsity athletes from the area flooded the arena.

“It was always apparent just how athletic these kids were,” Muir said. “So to see the absolute best in my class, in person, was a huge thrill for me.”

It only took a few minutes for Bryant to get going. Immediately after missing his first shot attempt, he caught an outlet pass on the fast break and soared high for a one-handed slam — the kind of play that NBA fans would enjoy over and over again for the next 20 years.

“You play PIAA basketball, and it’s not bad,” Muir said. “But then you see someone who is just silky smooth, and quick and explosive in person and you’re just in awe.”

Bryant finished with 13 points and three assists, impressive but underwhelming for someone as hyped as himself. Jackson and Syracuse commit Winfred Walton led the game in scoring with 21 points each. Seton Hall commit Shaheen Holloway took home the game’s MVP award, putting together seven points, eight assists and six steals.

Despite the performance, the media hustled to Bryant at the final horn.

“He had all these TV cameras and reporters around him,” Kovak said. “I can just remember seeing this smile on his face and dealing with it.”

Bryant’s heartbreaking death brings greater attention to some of the Field House’s legendary history. Most Pitt students likely had no idea that Bryant ever graced Pitt’s campus until after his death. The Field House, opened in 1951, will close in the next few years as Pitt starts construction on its ambitious Victory Heights project.

Junior outside hitter Kayla Lund, named the 2019 ACC Volleyball Player of the Year, has called the Field House home her whole career.

“A lot of us didn’t know that Kobe had played here until that video was going around,” Lund said. “That makes it really unique. When you’re watching that video you see the Field House, you see Pitt. Going into practice, it’s a little heavier … Especially the day after [the news of his death], when we practiced and we’re in the same spot that he was.”

Lund, who grew up just outside of Los Angeles, talked about the heartbreak of losing her hometown’s hero. She especially appreciated his athletic bond with Gianna.

“It really kind of hit me because it was Kobe and Gigi,” she said. “The bond between a father and daughter shared by sports is something so unique. It’s something that my dad and I have.”

From the time he stepped onto the court at the Fitz, Kovak knew he was witnessing a special player.

“He had a graciousness about him,” Kovak recalled. “Just sort of a maturity and a confidence about him most of the other kids didn’t have. A lot of the other kids, there might have been a little bit of a cockiness there, but you could tell Kobe was just very comfortable with the attention. He knew how to handle it.”

For Bryant, the weekend may have just been one small speck on a decorated and illustrious career. For those in attendance that weekend 23 years ago, it was a memory they will never forget.