Remembering Richard ‘The Rev’ Ricci: Pitt alum and spiritual force behind ‘Night of the Living Dead’

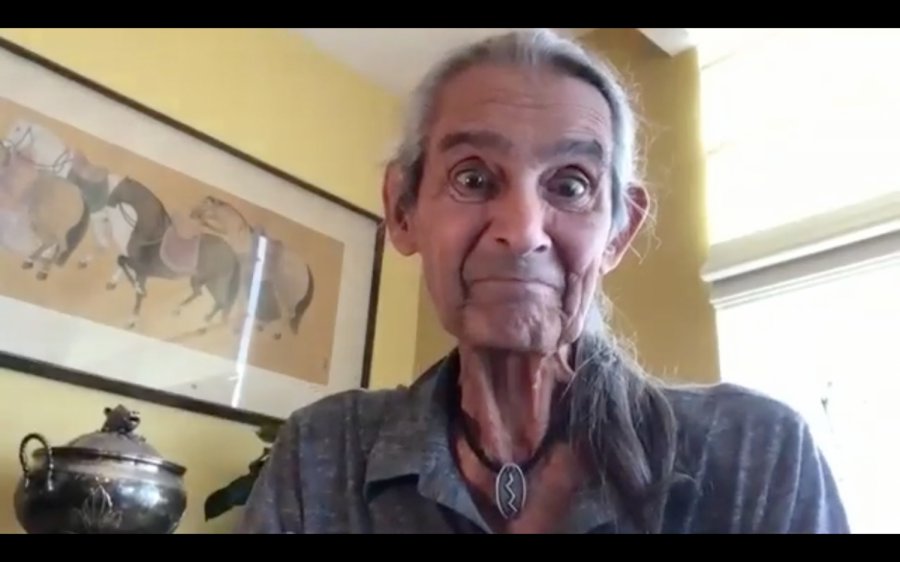

Photo courtesy of Claire Akers

Richard Ricci passed away on July 15 at age 80, almost exactly three years after the death of his friend, “Living Dead” director George A. Romero.

August 26, 2020

It’s a classic trope in horror movies, so much so that it almost feels like common sense. If you want to kill a zombie, you go for its brain.

But this conventional wisdom wasn’t part of the public consciousness until 1968, when actor and producer Richard Ricci appeared as the first ghoul to take a bullet to the head in “Night of the Living Dead.”

An integral part of Latent Image — the independent, Pittsburgh-based company behind the film — Ricci provided inspiration, friendship and the occasional spiritual guidance to his fellow filmmakers. Ricci passed away on July 15 at age 80, almost exactly three years after the death of George A. Romero, his friend and “Living Dead” director.

The world remembers Ricci through his work with Latent Image, and Pitt students in the film and media studies program remember him through his contributions to the course “Making the Documentary: George Romero and Pittsburgh.”

Students who took the course last spring worked on a documentary about the making of “Night of the Living Dead,” and Ricci participated in interviews about his involvement in the film. Carl Kurlander, who taught the course, said he felt Ricci’s appearance left a lasting impact on both himself and his students.

“We were so lucky to be able to meet Richard,” Kurlander said. “My students said they could tell what a good soul he was.”

According to Kurlander, Ricci met Romero through his cousin in 1960, during Ricci’s senior year at Pitt. Kurlander said they shared a love of film and frequently watched movies together, thanks to Ricci’s job operating projectors at Pitt.

The two became close friends and collaborators, so much so that Kurlander said he thought the director “would never have done ‘Night of the Living Dead’” had it not been for Ricci.

“George had literally learned everything about filmmaking not at [Carnegie Mellon University, where he attended college],” Kurlander said, “but at Pitt with Richard Ricci.”

After graduating in 1961, Ricci joined Romero and several other friends in creating Latent Image. According to Claire Akers, a 2019 Pitt alumna and TA for the documentary course, the company produced their first film together — called “Slant” — on the Duquesne Incline.

Akers said the short film, the footage for which no longer exists, followed the story of a young girl dreaming of a better life.

“[She] dreams of going up the Incline, and when she gets there she realizes it’s not all she thought it was. So she goes back down and realizes she likes her life,” Akers said.

But Latent Image didn’t produce a full feature-length film until “Night of the Living Dead” — which Ricci also had a major hand in developing.

The film is loosely based on the Richard Matheson novel “I Am Legend,” about a post-apocalyptic world overrun with vampires. And according to Kurlander, Romero only knew about the book because of Ricci.

“Richard was the one who gave George a book called ‘I Am Legend,’ which is the book that ‘Night of the Living Dead’ was based on,” Kurlander said.

Gary Streiner, another member of Latent Image, said Ricci also contributed to the film by convincing its collaborators to fund the project.

“He was the financier of Latent Image. He infused it all with a lot of cash,” Streiner said. “He was the one that inspired each of us — there ended up being 10 of us — to put up whatever cash we could.”

Streiner added that Duane Jones, the film’s lead actor and one of the first Black men to play the hero in a horror movie, joined the production because he and Ricci were college roommates. Streiner said Ricci convinced him to audition for the part, despite the fact that Jones had moved to New York.

“Duane, after college, was ready to get out of Pittsburgh. He was ready to find higher ground,” Streiner said. “He was back in town over the holidays. Duane came and read for George, and there was just no question about it.”

And as for that infamous head shot scene, Ricci told the film class that Romero selected him for the part out of necessity. According to Akers’ interview with Ricci, the scene was potentially dangerous, and Latent Image couldn’t afford a lawsuit if it ended badly.

“George said, ‘Oh, Richard, listen, I have something. I want a roll for you for your zombie,’” Ricci said. “‘We want you because you won’t sue us if anything happens.’”

On a personal level, Streiner described Ricci as spiritual, and said he earned the nickname “The Rev” among friends for the way he “always had an answer.”

“He never rushed his answers — he always took time to think them out,” Streiner said. “That’s the way he was about everything. It would take him an hour to eat an orange, he was so particular about the process.”

Streiner said Ricci also had rituals for even miniscule, everyday activities — something he said exemplified Ricci’s careful nature and earned him respect from friends.

“You couldn’t just have a fire in the fireplace without there being some ritual attached,” Streiner said. “Everything got that special attention. That’s why he was so loved by everyone that knew him. It was because he took time to listen.”

Although Akers knew Ricci for only a few months, she said she grew close with him through their interviews, adding that he took an interest in her goals as a filmmaker.

“He had asked me — what am I interested in, and what do I want to do,” Akers said. “He’s so personable that without even realizing it, you enter a full conversation.”

After making “Night of the Living Dead,” Ricci drifted apart from Latent Image, moving to Los Angeles and later Santa Fe, New Mexico, to pursue a behind-the-scenes career in film production, according to Streiner.

“He kind of left the pack after a while and went on to have a career elsewhere, which a lot of us did. We were all really really young when we started,” Streiner said. “You finally get to that point where you have to go out and use what you learned.”

Akers said Ricci often joked about being “the only one with a steady job [in Latent Image],” and Streiner also noted that even during the company’s heyday, Ricci drifted in and out to serve in the Navy or work for advertising companies.

“Richard was kind of out there. He had other jobs, he went to work, he was a producer at an advertising agency,” Streiner said. “He went away to the Navy, and he kind of separated from the pack.”

Still, Ricci never put too much distance between himself and Latent Image. He eventually settled in Miami, where he lived until his passing, but regularly returned to western Pennsylvania to participate in the annual Living Dead Weekend, according to Streiner.

Akers said at the time of his death, Ricci was also working with the George A. Romero Foundation to restore footage from Latent Image’s unfinished feature film, “Expostulations.”

During one of his interviews for the documentary, Ricci recalled the confidence and determination he felt when he and Romero decided to start a film company — a decision that eventually led to “Night of the Living Dead” and solidified Ricci’s legacy in the horror world.

“[Romero] said, ‘I’m going to make movies with Richard Ricci,’” Ricci said. “No doubt in our minds. This is what we’re going to do.”