Welcome Back: Local pair envisions new Panther football stadium

August 19, 2013

Pitt’s mascot, the Panther, was named after the mountain lions that once called Panther Hollow home.

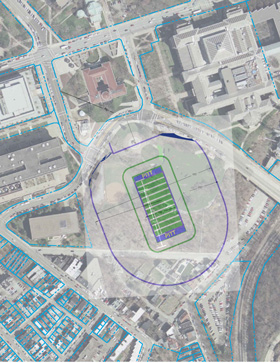

This relatively isolated section of the neighborhood, a section of Central Oakland that runs along Boundary Street, has been cited by some — including a group of enthusiastic Pitt alumni — as a potential area for a new on-campus football stadium. But don’t expect the modern day Panthers to call the Hollow home any time soon.

Although Pitt and local community organizations have expressed their skepticism, Mike Andra and John Mack, two Pitt alums, are adamant that an on-campus stadium will benefit not only the University, but the Oakland community as a whole.

For Andra, it boils down to two simple factors: the game-day experience and economics.

“If the game-day experience is fun, people will go as opposed to watching on TV,” Andra said in an email. “If people hang out before the game because there is more to do and see, people will spend more money. Money in Oakland small businesses and University pockets is a good thing.”

Beginnings

According to Mack, a 1977 graduate of Pitt’s School of Engineering, his grassroots efforts to introduce a plan for building an on-campus stadium began after he and other users of the Pitt fan blog, Pitt Blather, began discussing a post on The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s community blog, written by John Baranowski. The post originally appeared on Bleacher Report.

The discussion garnered a number of responses, and one of the respondents was Andra, a 1992 graduate. At that point in time, Mack had already created a website dedicated to the idea of building a new Pitt stadium in Panther Hollow. Andra said he was highly impressed with the website, especially since Mack admitted that he had little experience in website design.

Though they live in different parts of the country — Andra in Texas and Mack in Pittsburgh’s North Hills — the two men soon developed a friendship based on their love of Pitt and their passion for a new on-campus stadium. Their vision attracted about 12 other members to the group.

The Plan

Mack and Andra’s plan is far from short-term. Both men consider the plan a long-term solution to Heinz Field’s inevitable deterioration within 20 to 25 years. They say that Pitt needs to consider where the football team will play if the Pittsburgh Steelers decide to build their next stadium in a location outside the Pittsburgh city limits.

From the outset, Mack knew that he didn’t want the new facility to serve simply as a home to the football team. In addition to a stadium that could hold from 44,000 to 50,000 people, his plan includes a dormitory built into the stadium, a track surrounding the field for the men’s and women’s track and field team and an area for office space.

But in his opinion, the most crucial portion of the plan is its emphasis on highlighting the aesthetics of Pitt’s campus, which factored into his decision to pinpoint Panther Hollow as the decided location.

“So I thought about it and said, ‘What makes Pitt “Pitt?” The Cathedral,” Mack said. “Well, then, the stadium should see the Cathedral if it’s on campus,” adding that the iconic building and the Mary Schenley Fountain will be visible from the stadium’s open entrance.

Of course, Pitt’s urban campus presents a number of space constraints. In order to make room for the large new complex, a number of properties in Panther Hollow between Joncaire and Boundary streets and Yarrow Way would need to be purchased. In addition, Mack said the Frick Fine Arts Building would need to be moved onto Schenley Plaza, and Mazeroski Field would be demolished, though he said the new stadium would also include a Pittsburgh Pirates museum.

The next area of concern for Mack and Andra is parking and transportation.

Mack said the plan includes the building of a multi-level parking garage that could hold between 1,200 and 1,500 vehicles. He also said that the Allegheny Valley Railroad could expand its commuter service operations and extend into Panther Hollow using the pre-existing railway.

In a project of this magnitude, cost is always a factor, and Mack and Andra readily admit this. They project that, in total, the project would cost $700 million, with all funding coming from alumni benefactors. They also projected that the new stadium would lead to about $47 million in revenue during its first year.

Andra said in an email that cost and revenue projections were based on a cost analysis recently performed by Colorado State University in regard to building a stadium on the university’s campus. He said a project of this magnitude wouldn’t begin until a funding source is guaranteed.

Though the plan is in its early stages, Mack said they’ve formed a nonprofit organization and are beginning talks with an architectural firm to create a number of renderings. Once this is completed, he said, they’ll begin working with an engineering firm to conduct a prefeasibility study, which he said will assess not only the engineering requirements, but also whether the various parties involved, such as Pitt and Carnegie Mellon University, would be interested.

He estimated that this study will cost between $400,000 and $500,000.

“There’s no particular reason why [the plan] couldn’t work,” Mack said.

Resistance

Although Mack and Andra maintain that their plan isn’t just a fantasy, some of Oakland’s most powerful institutions oppose the idea as it currently stands.

“The University is aware of this initiative but is not supportive of it for numerous reasons. We are committed to our relationship with the Pittsburgh Steelers and Heinz Field as the home of the Pitt Panthers,” Pitt spokesman John Fedele said in an email.

Pitt Senior Associate Athletic Director E.J. Borghetti elaborated on Fedele’s comments in an email, saying that Heinz Field and its association with the Steelers presents an opportunity that few other college football programs across the country can boast.

“Heinz Field is an important recruiting tool for our program,” Borghetti said. “It makes a great impression on a prospect when they walk through the stadium gates that read ‘Panthers’ and ‘Steelers.’ It reinforces the message that we play in the best football city in the country and have as a close partner one of the world’s greatest pro-sports franchises.”

But Pitt isn’t the only obstacle in the path toward a new on-campus stadium.

Wanda Wilson, director of the Oakland Planning and Development Corporation, said an on-campus stadium does not align with the organization’s long-term plans for the Oakland community.

“The proposal, as I understand it, would not be consistent with the Oakland 2025 Master Plan,”Wilson said, adding that the Oakland 2025 plan includes improvements to housing, transportation and interaction between community residents.

For residents of Panther Hollow, the rumblings of Pitt expanding its athletic program’s facilities into the neighborhood they call home is nothing new.

According to an article that appeared in a 1993 issue of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pitt originally proposed building a new basketball arena in Panther Hollow to replace the Fitzgerald Field House. The plan was quickly rejected.

Bob Senko, a resident of Boundary Street, said though he’s indifferent to the idea of a stadium being built in Panther Hollow since he plans to move away next year, he doesn’t believe a project of this kind will come to fruition any time soon.

“It’s all a bunch of talk,” Senko said.

Carnegie Mellon media representative Stephanie Williams said the university doesn’t respond to speculative inquiries.

Pittsburgh District 3 Councilman Bruce Kraus was unavailable for comment because City Council is in recess.

Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Andra said he isn’t surprised that Pitt doesn’t support the plan at this point in time. He believes that the Chancellor Mark Nordenberg’s administration would not want to support a new on-campus stadium plan after approving the demolition of Pitt Stadium in 1999, saying that it would be a “tacit admission” and that they made a mistake.

But Nordenberg’s retirement next August brings a new opportunity since, in Andra’s opinion, a new chancellor would want to leave a lasting legacy on campus.

Organizations such as OPDC, CMU and the city of Pittsburgh will support the plan once they understand its feasibility, Andra said. But more importantly, he added, the plan could help highlight Oakland’s distinct culture and vibe.

“This helps everyone better connect with the University…not the city. Although we carry the city’s name, we are a product of our urban village called Oakland. We should be proud of that heritage,” Andra said in an email.