Despite the promise of creating 600 permanent jobs, the ethane cracker plant being built about 40 minutes northwest of Pittsburgh by car continues to face scrutiny from environmental groups.

Shell Chemical Appalachia decided in 2012 that Beaver County would be the site of a new $6 billion plant to manufacture plastics. Shell chose the Beaver County location because of its proximity to natural gas supplies and because the majority of North American polyethylene — the most common plastic — customers are in a 700-mile radius of Pittsburgh.

In a statement published on its website, Shell said it expects to employ around 6,000 people for the facility’s construction, support 600 permanent employees and create an economic boom in Southwestern PA.

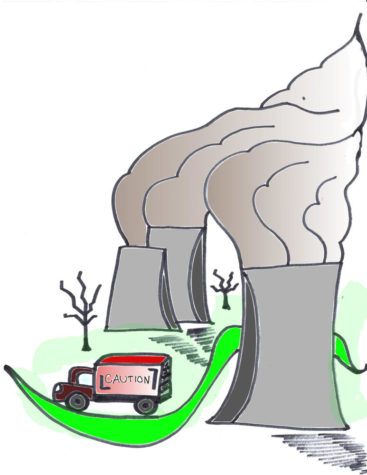

The plan to build the plant — dubbed a cracker plant because it takes oil and gas and “cracks” it into smaller molecules to produce ethylene, a building block for plastic — concerns environmentalists who say this plant will emit excessive pollution, which will increase Pittsburgh’s already high pollution levels. In the American Lung Association’s 2017 report, Pittsburgh ranked eighth for annual particle pollution out of 184 metropolitan areas.

Junior Sarah Grguras — a sustainability program assistant in Pitt’s Student Office of Sustainability and an environmental studies and ecology and evolution double major — is familiar with current and historical air pollution issues in Pittsburgh. She said pollution from the plant is going to diminish Pittsburgh’s air quality.

“It’s going to turn Pittsburgh into cancer alley,” Grguras said. “It’s not a long-term help, and it’s not a sustainable industry.”

Following a lawsuit, the Clean Air Council and the Environmental Integrity Project — two environmental advocacy groups — made a deal with Shell to install four “fenceline” monitors, or pollution detectors, along the perimeter of the facility. This will allow the surrounding community to receive updates on a public website if the plant’s emissions are linked to air pollution and exceed a certain threshold.

Based in Philadelphia, Joseph Minott, 63, who is both the executive and chief counsel for Clean Air Council, said even though this deal was made and Shell will install monitors, pollution will still occur.

“What our lawsuit did was try to make sure that the technology they use at the plant is the best technology, so it will minimize the impact on the local citizenry,” Minott said. “But it does not ensure that the plant will not be emitting any pollution.”

When asked specifically about the precautions Shell Oil Company is taking in order to prevent pollution, Ray Fisher, a spokesperson for Shell Oil Company, wrote in an email that the plant will utilize the “best technology available to control emissions along with fenceline monitoring” and Shell will make the data available to the public.

“In addition, we worked with the Commonwealth to offset emissions in a manner that will create better air quality over time,” Fisher wrote in the email.

Fisher did not answer specific questions regarding how Shell plans to prevent shale emissions.

Emeritus Professor of Pitt’s Graduate School of Public Health Bernard Goldstein, 78, is concerned about the impacts the plant will have on the environment and public health. Goldstein explained the plant utilizes the nearby wet gas from Marcellus Shale — a unit of sedimentary rock that contains untapped natural gas reserves — to convert methane and other gases into plastics.

Since the petrochemical plant is so large, it will be subject to both state and federal regulations, including those from the Environmental Protection Agency. Goldstein said he is not as concerned about the plant itself because of this oversight.

“The pollution that I’m most concerned about comes out of the drilling and obtaining the shale gas, which is then used as feedstock for this chemical plant,” Goldstein said.

Goldstein said the construction of the cracker plant will create more sources of shale gas emissions. Goldstein and Evelyn Talbott, an epidemiology professor at Pitt, agree that, because the drill sites are small — but numerous — these sites are not regulated as well.

“When you’ve got 20,000 sites, how could you possibly check them everyday?” Talbott said.

Shell did not respond to questions about the specific types of pollution detectors it will use around the plant and whether these small drilling sites can produce additional shale emissions.

The EPA has standards that regulate six different air pollutants. Talbott said ozone (O3) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) are two pollutants that the plant could potentially emit, which could lead to health problems.

“Ozone … is bad for your lungs and is related to asthma. Nitrogen dioxide is also a pulmonary irritant that can cause pulmonary and respiratory disease,” Talbott said. “If you boil water and turn on your gas stove, there is a certain amount of NO2 that is a fossil fuel emission, so in the Marcellus Shale industry there’s bound to be nitrogen dioxide.”

From an economic standpoint, companies such as Marcellus Shale Coalition see this project as a game changer. President of Marcellus Shale Coalition, David Spigelmyer, released a statement June 7, 2016, saying that Shell’s decision to build the plant is “welcomed news.” The Pitt News called the Marcellus Shale Coalition several times and did not receive a response over the course of four business days.

However, environmentalists Grguras and Minott said there are other ways to create jobs without harming the earth. They said evidence supports more long-term jobs will be with green energy — such as solar, wind and geothermal.

“The green economy, where other countries are way ahead of us, produces far less pollution, employs more people and is more sustainable,” Minott said. “We seem stuck on fossil fuels in Pennsylvania.”

Many are worried about the fate of Pittsburgh’s air, but at the same time, many see the promise of jobs as a positive outcome.

“It’s a trade-off,” Talbott said. “Everyone wants jobs and for our economy to flourish, but I think there’s a lot of concern by environmental groups that the pollution is not going to be curbed and it could be a problem.”