Clean air policies go up in smoke

Industrial activity is a major contributor to Pittsburgh air pollution.

November 12, 2018

Pittsburgh was named the second most livable city in the United States a few months ago in The Global Liveability Index, an annual report by The Economist Intelligence Unit. But take healthcare, education, entertainment and other factors out of the equation and look solely at air quality, and the City’s ranking drops drastically.

Pittsburgh is ranked the eighth worst city in the country for particle pollution by the American Lung Association and received straight-F grades for particle pollution and ozone levels. And according to local clean air groups such as Pittsburgh’s Breathe Project and Clean Air Council, Shell Oil Company’s upcoming ethylene cracker plant — projected to open in the early 2020s in Potter Township, 30 miles away from the City — may drop those rankings further, increasing air pollution and endangering the health of Pittsburgh residents.

Pittsburgh isn’t a newcomer to low rankings in air quality. The days of steel mining may have come and gone, but the City of Steel still has a difficult relationship with air quality due to its location and the high density of manufacturing plants. For residents of Pittsburgh and surrounding areas, bad air quality translates to a higher risk for a wide variety of health conditions, ranging from asthma to childhood cancer to diabetes.

Dr. Matthew Mehalik is the executive director of Breathe Project, a Pittsburgh-based group that aims to make accurate air quality information easily accessible to the public. He said part of the challenge that the City faces with cleaning up its air is that nearly 60 percent of the air pollution comes from industrial plants.

“Our airshed is unique compared to other cities around the country that struggle with bad air quality. Places like Los Angeles, and so on, they mainly have mobile sources like cars and trucks,” Mehalik said. “Pittsburgh is different. Our air pollution is mostly industrial sources.”

According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, more than half of the pollution in Pittsburgh is “remote,” meaning it comes from other areas in a 500-mile radius. Dr. Aurora Sharrard, director of the University’s Office of Sustainability, said the geography of the City makes it extremely difficult to eliminate this air pollution.

“Pittsburgh suffers from inversion, which means essentially the topography and hills and mountains around us work against us in having better air quality,” Sharrard said.

The geography also makes it difficult to measure the quality of the air throughout the City, according to Chris Ahlers. Ahlers is a staff attorney at the Clean Air Council, an environmental organization that focuses on sustainability and public health in the mid-Atlantic.

“The mountains and valleys of the region can cause a concentration of air pollutants at a particular location,” Ahlers said, “Which can cause the data at air quality monitors to be unrepresentative of the air pollutants that people actually breathe.”

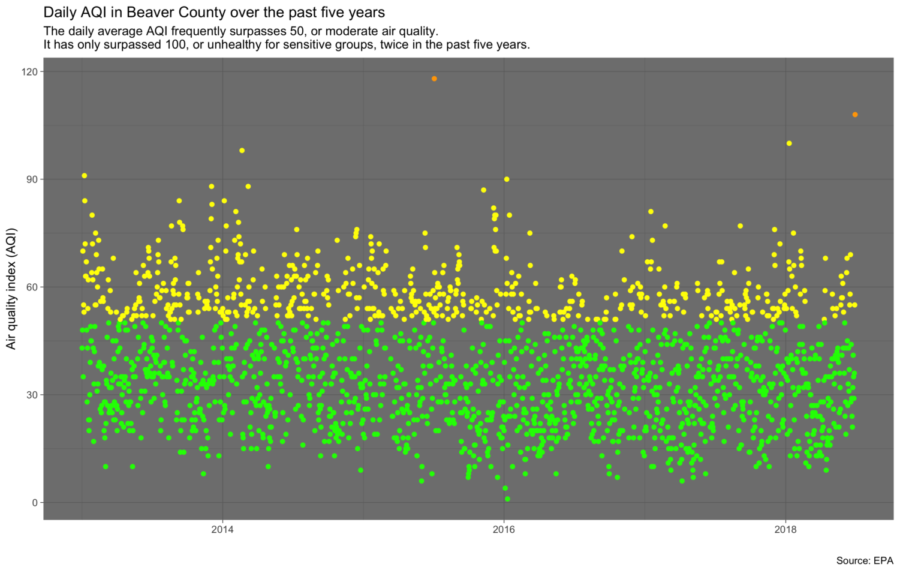

The City has seen slow-but-sure progress since the steel mills became defunct in the early 1980s, but still fails to meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s standards. The EPA’s air quality tracker notes that in more than two-thirds of the days in 2016, Pittsburgh’s air quality was deemed “not good” because of high presence of multiple pollutants.

Environmental experts like Mehalik worry the progress made so far will be stunted by the addition of three new ethylene cracker plants planned in Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

“Our region is still out of attainment of national standard for air pollution, for particulate matter,” Mehalik said. “We’re still not meeting what’s legally required.”

Brian Gentry | Online Visual Editor

Brian Gentry | Online Visual Editor

Shell Oil Company announced in June 2016 that it would construct an ethylene cracker plant in western Pennsylvania. The site, which will be called Shell Polymers, is located 30 miles from Pittsburgh in Beaver County’s Potter Township. The plants will take ethane and heat it up until it “cracks,” or transforms into ethylene, a key component in the production of plastics. According to a press release from Shell, once it opens in the early 2020s, the Pennsylvania plant is expected to produce 1.6 million tons of polyethylene each year.

Shell’s emissions permit said they plan to emit 522 tons of volatile organic compounds each year. This would make the cracker plant the largest emitter of volatile organic compounds pollution in western Pennsylvania and the third-largest in the state. VOCs are released as gases during the production of certain liquids and solids, and have many negative health impacts.

With this projected increase in pollution, the progress that Pittsburgh has made in eliminating VOC pollution would be erased, according to research done by Pitt environmental and occupational professor Jim Fabisiak. Shell did not respond to a request for comment.

Mehalik and his team took the data from the emissions amounts that Shell was approved for in their permit and used an EPA tool known as Cobra, or CO-Benefits Risk Assessment, to model the impact of the increased air pollution on health care costs for Allegheny County.

“What we were able to determine, to summarize the increased health care costs that come from more respiratory distress, more asthma, more emergency room visits and more cardiac events, that Allegheny County’s health care costs will go up somewhere between 15 and 32 million dollars a year,” Mehalik said. “If you have this plant that operates for 30 years, then that’s going to be somewhere a billion dollars of added health care costs for Allegheny County.”

This is of particular concern to environmental groups like Breathe Project because Pittsburgh already continuously fails to meet the federal government’s standards for ozone, fine particulate matter and sulfur dioxide.

“We struggle with that. Our region is still out of attainment of national standard for air pollution, for particulate matter,” Mehalik said. “We’re still not meeting what’s legally required.”