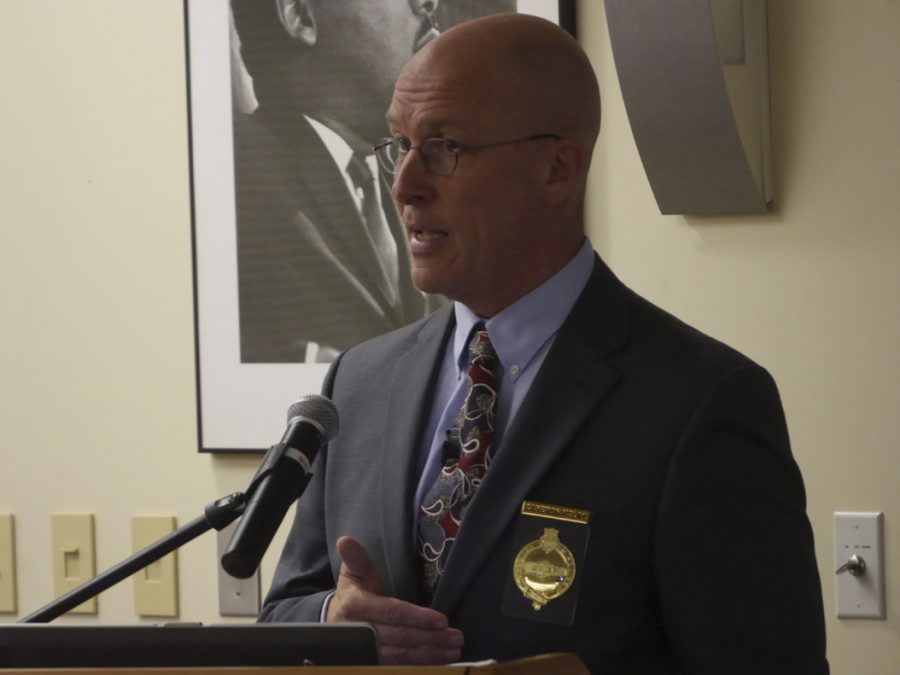

Just two years ago, Pittsburgh Chief of Police Cameron McLay came to the city as a reformer.

His predecessor had just been sentenced to a term in prison. Relations between the police force and community had been fraying for years. He had a tough road ahead.

But the former Madison, Wisconsin police captain navigated an often-hostile police force and implemented important reforms to work toward a better relationship between the community and those hired to protect and serve it.

On Friday, McLay announced his decision to leave the department, saying that he’s accomplished everything he thinks he’s able to do here.

During his tenure, short-lived as it was, McLay worked to alleviate racial tensions between the police force and Pittsburgh’s minority communities, made police more visible to the community and pushed for officers to undergo implicit bias and other new types of training.

Now that McLay is leaving — tomorrow is his last day on the job — the city and his yet-to-be-named predecessor shouldn’t be afraid to continue working toward change.

At a news conference Friday, Schubert vowed to continue McLay’s reforms, and Pittsburgh should hold him to that. Before McLay came into office, community-police relations were strained, morale among the police officers was low and officers were retiring at significant rates.

During McLay’s time, total complaints against the police in Pittsburgh decreased 42 percent, there was a 51 percent decrease in lawsuits against police and the city was invited to be part of a national pilot program to strengthen police-community relationships.

Despite these positive changes, over time, the friction between McLay and the police department increased, creating a stark divide between McLay’s leadership and the rank-and-file members who resisted his changes.

Last month, the majority of the members of the police union voted that they had “no confidence” in his ability to lead. Whether it was McLay’s support for challenging racism in a social media post or wearing his uniform at the Democratic National Convention, the complaints against McLay were trivial compared to the issues happening in Pittsburgh’s own neighborhoods.

In the midst of tumultuous relations between police officers and communities of color nationally, McLay wasn’t afraid to be honest.

“If we are going to have legitimacy, if we are going to preserve the integrity of our brave profession, we must hold accountable those of our members who bring shame upon us. Misconduct by one brings dishonor to us all,” McLay said following the violence in Ferguson, Missouri.

A successor who would disagree with that statement, or not actively espouse that same desire for reform would be taking a step backward.

Asking for accountability isn’t a sign of disrespect, it’s a call for justice for those who have been mistreated in the hands of the law. Calling for reform isn’t an accusation of wrongdoing toward the police department, it’s a step toward improving the community as a whole.

While it’s important to have faith in a leader, it is also crucial to look at the big picture of what we want to be as a community and how we can get there. If that means recognizing the faults in our system, so be it.

McLay wasn’t able to complete his mission in the city, but it is up to the force he’s leaving behind to continue it.