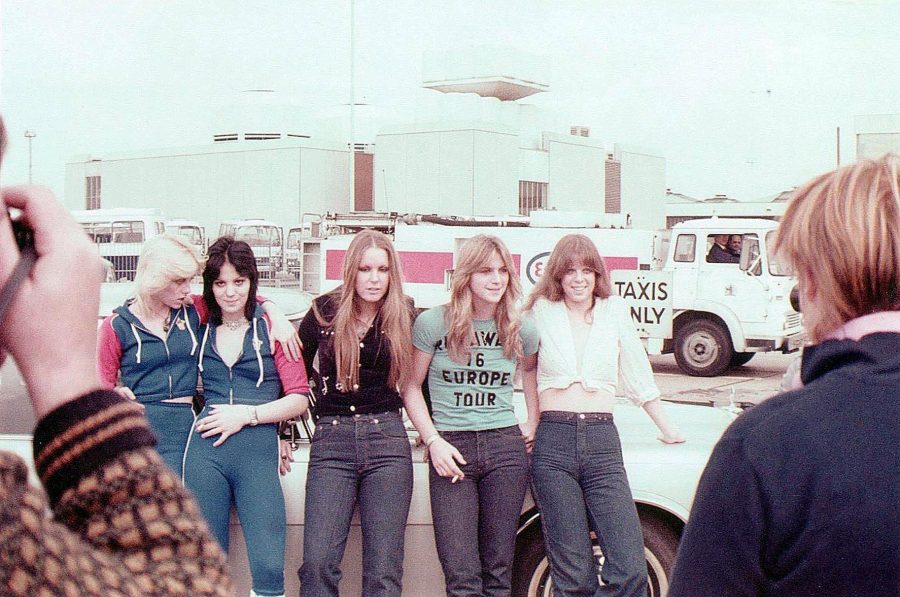

It was New Year’s Eve, 1975, and The Runaways — the all-girl rock band founded by Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Joan Jett — had just finished their last set at Wild Man Sam’s, a small club in Orange County, California.

At the time, Jackie Fuchs was known by her stage name — Jackie Fox. She was an eager 16-year-old bass guitarist balancing working in the band and at school.

Fuchs arrived at an afterparty at a nearby motel and was handed a Quaalude soon after. She was given four or five other pills as the night progressed. The drugs kicked in and Fuchs — normally in control of her actions — became incapacitated.

She was then raped in front of the crowd by her band manager, uninterrupted — no one intervened. She was conscious enough to recall part of the experience, but couldn’t do anything in her defense.

Until recently, it was a secret that she kept to herself — a secret shared only with her bystanders. Forty years later, Fuchs finally decided to speak out about her rape. Outlets like The Huffington Post and The Guardian have covered her experience — but Fuchs wants college students to acknowledge the event to gain a better understanding of the bystander effect.

Fuchs spoke to The Pitt News about her experience with the bystander effect, sexual assault prevention on college campuses and ways to increase bystander intervention.

The Pitt News: What is the bystander effect?

Jackie Fuchs: One thing studies have shown is that the more people that witness a wrongful act, the less likely they are to intervene. So if two people witness a sexual assault, there’s a greater chance they will intervene to stop it than if a dozen people witness it. I think this just goes back to if you’re part of a group, there’s a social dynamic going on at not an entirely conscious level. It’s just that you protect your group, your buddies, and if that’s a person you know, it’s hard to go against that social dynamic, and it does become somebody else’s responsibility. It has nothing to do, by the way, with morality. It doesn’t mean if you don’t interact or intervene, you’re a bad person or don’t know right from wrong. People who are completely moral can be just as frozen or inactive as people who are a little more callous.

TPN: Why do you think it’s important for college students to be aware of the bystander effect specifically?

JF: If you walk into a room and ask people, “Do you think you’re a leader?” probably most people in that room will put their hands up. But when something actually happens, something bad, because we don’t have that training — we’re not in the military, we didn’t go to the police academy — we don’t know how to stand up and take leadership in that kind of situation. Most of us will freeze and look to somebody else for what to do. It is a natural response when we see something bad happen, or someone being perpetrated by someone who is a dominant figure in the social group, for us to not go against that person in any way. The first step in preventing sexual assault on campuses is for people to recognize, “Oh, I’m sitting here just thinking ‘Oh, this is not good’ and not doing anything because I’m being affected by the bystander effect,” and there is diffusion of responsibility. I think recognizing you’re [under the influence the bystander effect] is the first step in overcoming it. I have talked to half a dozen people who said they felt incredibly guilty about not having done anything when I was raped, and it’s really a tragedy that they had to live with that.

TPN: You were juggling school and the band. Did you ever feel alienated from the other girls because of your academic focus?

JF: One of the things that I was very fortunate when growing up is my parents had friends from all kinds of backgrounds, so I was used to talking to a lot of different kinds of people. After that first semester with the band, I ended up in continuation because my mother wouldn’t let me quit school until the results of the GED high school equivalency exam came back. So, in continuation, I was in class with the kids who had trouble in regular school. They were people with learning disabilities or the “bad kids” and it prepared me for dealing with people in the music industry who were different than I was. After the fact, it’s easy to say, “Well, that’s what made me different from the girls in the band.” But the thing that made me different was that I didn’t use drugs and that I had been raped in front of the rest of them. And it turns out, that will put a lot of distance between you and the people who witnessed it.

TPN: Do you think this aspect of being sexually assaulted changed your experience with the band?

JF: At the time, I just didn’t think about it. You do your best to put that behind you and convince yourself that you’re not being affected by it. Being in a rock band was a lot of fun a lot of the time, but it was always the elephant in the room. I think that I acted out in a way that I otherwise probably wouldn’t have. It was very difficult sustaining relationships, which was hard enough when you’re in a band anyway, but whatever trust you have tends to be gone. Then you go through this yo-yo thing, where you realize you’re not trusting people, so you force yourself to be more trusting. But, because your compass for where trust should be and shouldn’t be isn’t properly calibrated anymore, it becomes very difficult.

I think I got myself into some situations that I shouldn’t have been in because I was trying too hard to be trusting. I didn’t allow myself to be comfortable around people who were very good because I was suspicious, so that was, I think, the worst part of what happened to me. One of the things you have to remember is I was unconscious for a lot of what happened, so in many ways it was far more difficult for the people who saw what happened to me and have carried around a lot of guilt for having not intervened.

TPN: In the Huffington Post Highline article, you mentioned that you weren’t the only victim of your manager having raped you, but so were the bystanders. Why do you consider the bystanders of events like yours to also be victims?

JF: One of the things you have to remember is that the people who were also in that room were also very young. A lot of them had been doing drugs and drinking that night. The person who raped me was an authority figure within our group, and it was also a group that had a common purpose. In that way, a rock band was similar to a sports team or a fraternity, in that it was a group we very much wanted to be a part of. It added some pressure to the group to not go against the person who was an authority figure in that group. There were a lot of reasons people found it difficult to act that night. You can ask people who aren’t in that situation what they would do, but until you’re in it, you just don’t know. It’s not clear, maybe, at the beginning that what you’re seeing is not consensual.

I think that part of what happens when you’re at a party and you see someone, who’s a little drunk maybe making out with someone else, who’s also maybe a little drunk, it’s hard to tell there’s something bad going on initially. By the time it becomes apparent, you’ll be a little complicit when you’re watching, that it’s just that much harder to act. You look around and you see other people not doing anything, and it gets harder still to go against the group. But, because you know it’s wrong, there’s a voice inside your head saying, “I should do something, I should do something,” and then there’s another voice telling you why you shouldn’t. What happens is, over time, that initial voice that tells you you should do something turns into tremendous guilt that you could have prevented what happened. For the people watching, they really didn’t know what to do, but they still thought they should’ve done something. Because they didn’t have the emotional vocabulary to talk to me about it, it just festered — both for me with my own sense of shame and self blame, and for them with the self blame of not having done anything.

I know this because I’ve spoken to a lot of the people who had been there that night, and a lot of them told me how guilty they felt that they didn’t stop it. One of them said it ate away at him for 40 years and he only ever told two people about it. Now, I find myself in the position, after the story came out, of having to comfort them and telling them that I didn’t hold them responsible for it. Nobody told them what they could have done. It’s just something they thought about.

I hope by speaking out, I can help change that. Maybe people will have a discussion with their friends about what they would want their friends to do if they see them getting into a compromising situation. I think it would be great if guys in particular not only looked out for women but for each other, and if they saw one of their friends getting into something with a girl or a guy who was a little bit drunk or otherwise wasted that they would have permission from their friends to stop that from happening. I think it would be really nice if guys talked about this in advance because when you’re in that situation and you have drugs and maybe alcohol and definitely hormones screaming encouragement, it’s going to be hard to stop something from happening. It’s a lot easier to know you have permission to step in and say to your friend, “Hey, I think she’s a little too drunk, you don’t want a problem here, follow up on her tomorrow, she’s still going to be interested. And if she’s not, someone else will.”

TPN: Why do you think people are hesitant to blame their perpetrators, and why didn’t you come out to blame the actual perpetrator until later?

JF: I think that part of it is, when you’re the victim of an assault you feel you really didn’t have any control, and blaming yourself or blaming the people who stood there is the way of thinking that you could have prevented this assault if only you did something different. I don’t think people like feeling helpless, so you get things like some fairly prominent women who are standing up and saying I was drunk when I got raped and I was hanging around the wrong people, therefore I’m responsible for what happened to me. They have said that saying you weren’t indicating you don’t have any control over yourself or your life, which is pretty telling. It’s hard to admit that there are situations where we end up powerless. You have to remember, most people who commit sexual assaults are not people who misunderstood the signals, they are predators. It’s very disempowering to think that you can be in the authority of a predator at any point, but the truth is, you can. And that’s why the best way to stop a predator is to encourage the community to take part in preventing things like this from happening — not just sexual assault, but also bullying and harassment — and to really look at how our inaction can encourage these kinds of things to happen.

TPN: Who do you think can be a victim of sexual assault?

JF: Anybody. Babies are victims of sexual assault, so are old people. Anybody can be. It’s a really underreported crime. There’s probably more of it going on in places where you have the kind of situation like what happened to me or what happens on campuses — tightly knit groups of people that know each other. But that’s one of the big myths, which I think has changed since I was a teenager. In my day, a rapist was a guy hiding in the bushes with a knife, you know, forcibly grabbing somebody with a weapon. Most sexual assaults are committed by someone the victim knows — we are all at risk. And look, you can drug a 260-pound linebacker, but let’s face it, most of the time it’s women being attacked by more, slightly built men. It’s people of any age, it has very little to do with how the victim is dressed or how they’re acting or how tough they are. It’s a crime of opportunity.

TPN: Why do you think it’s important for students on college campuses to know what qualifies as consent?

JF: The law is very clear about what constitutes consent. I’m familiar with the California laws on rape and not the Pennsylvania ones, but they’re probably similar. In order to get consent, you’ve got to be, well whatever the legal age of consent is in your state. In California it happens to be 18, so if you’re 18 or older, it is very clear. There is no consent if the victim is unconscious or asleep or too inebriated to give meaningful consent or is unaware of the other person’s identity, which is a strange one, but it does happen. The fuzzy area you get into is where somebody is too inebriated to give meaningful consent. It’s really hard for young people to interact with each other without the social lubricant of alcohol.

One of the reasons I think it’s so important to talk about the bystander effect and what bystanders can do is that there can be an awareness in crowds that might not apply to an individual, where one person might not be sure if someone’s too [messed up] to give consent. In a group of people, there can be the sense that this isn’t a good idea, and it only takes one person to say, “I’m not sure about this,” and take a step back. And so, that’s why I think college kids in particular really need permission to look out for each other.

TPN: What advice do you have for students in particular in how to avoid sexual assault?

JF: I think the best thing they can do is talk to their friends about what they think they would do if they found themselves in that situation and how they would want their friends to react if the friend saw them in an ambiguous one.

TPN: What advice do you have for students who have been victims of a sexual assault or have witnessed one?

JF: It’s never too late to do the right thing, and just know, it is not your fault. The only person responsible for a sexual assault is the person committing it, because even if you made a mistake, a mistake is not an excuse for rape.

TPN: How would you relate your experience to that of any college students?

JF: I was barely 16 at the time, so I was within a similar age range as college students — before your frontal cortex is fully set and decision making comes a little easily. I was part of a very tightly knit social group, and a rock band can be very much like a sports team or the people in a fraternity — it’s a group of young people with a common purpose. We were at a party and there were a lot of drugs and alcohol around, and you had somebody who was the clear alpha person within that group that was engaging in illegal behavior. It was very hard for people to act or prevent it, and unfortunately I think the only thing that has really changed between then and now is our knowledge of the bystander effect and we have a much better dial now on what constitutes sexual assault. So, it’s getting easier, but I’m shocked we’re not further along 40 years from when I was raped. It’s still very hard for victims to come forward, and shame is a big part of it. So we need to make sure that the message gets out.

Marlo Safi primarily writes about public policy and politics for The Pitt News.

Write to Marlo at [email protected]

Editor’s note: This Q and A is accompanied by a corresponding column on the bystander effect. For corresponding column, see “Recognize the bystander effect: Combating the bystander effect begins with conversation.”