Editor’s note: This column complements a Q and A The Pitt News conducted with Jackie Fuchs, of “The Runaways.” For the Q and A with Jackie Fuchs, see “Q and A: Jackie Fuchs of “The Runaways” talks about her experience with sexual assault.”

I have fallen prey to the bystander effect — and so have you.

I have sat on a crowded bus — like everyone else — while an elderly woman walked on, waiting for others sitting on the bus to give up their seat. Someone has to, and someone else will, on a bus full of people.

The bystander effect shadows even the simplest of moments.

You drive past a car accident on a highway and assume someone else has called 911. You enjoy long showers and don’t try to limit yourself — other people will conserve resources, and you can afford to consume in excess. You like a post on Facebook denouncing a horrifying act, but your actions end there. There’s no obligation to intervene when you’re not the sole observer.

The bystander effect makes a routine appearance in our lives. Often times, neglecting to intervene in a potential incident doesn’t have catastrophic consequences.

But, in the case of Jackie Fuchs, the absence of bystander intervention led to a tragedy.

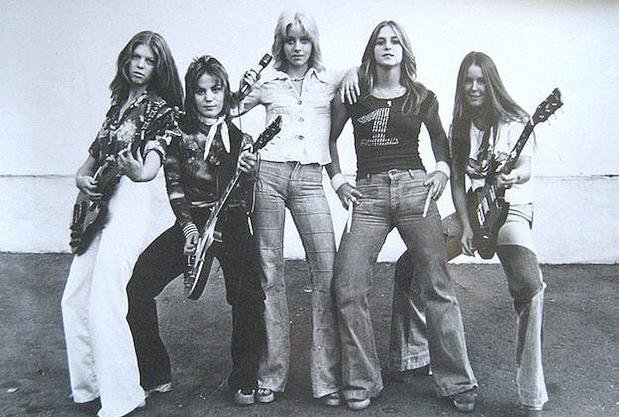

Fuchs, a former member of the all-girl ’70s rock band The Runaways, was raped by her manager in front of a crowd — an event that changed her life and the lives of the bystanders who witnessed it.

They were teenagers under the influence of drugs and alcohol. They had never been taught what to do in the event of an assault. They were pressured against intervening because the alleged perpetrator — the band manager — was a figure of authority.

“I didn’t know what to do,” then-14-year-old Kari Krome, a fellow bandmate, said to the Huffington Post.

“It was one of those times you feel like there’s a spotlight on you,” Brent Williams, a partygoer and friend of Krome’s, said to the Huffington Post. “Everybody’s looking at you to see how you would respond. You just want to get out of there.”

“Nobody seemed to really care,” said Helen Roessler, a friend of Fuchs who attended the party, to the Huffington Post. “It was really weird. Everybody was sitting in there alone with themselves. It felt like everyone was detached or trying to pretend like nothing was going on.”

I thought I knew what the bystander effect was prior to my interview with Fuchs. But I only knew the textbook definition — in an audience, there is a diffusion of responsibility that decreases the likelihood of intervention by individual participants.

And yet, when I witnessed the bystander effect in person — someone at a party pressuring another, well past their limit, to take a shot, for example — I idly stood by.

I’m not the only one who has remained silent in a crowd.

Pitt participated in an American Association of Universities survey that examined sexual assaults on campuses. The results of the survey made me realize that bystander passivity was a common response to disconcerting events. Jackie’s experience, and the reality of the AAU survey, present valuable lessons for encouraging bystander intervention.

According to the AAU Sexual Assault survey results, 43.7 percent of student respondents reported witnessing a drunken person heading for a sexual encounter. Among those bystanders, 79.7 percent did nothing, 23.7 percent weren’t sure what to do and 56 percent did nothing for another reason.

The results have garnered an increased sense of urgency to reinforce bystander intervention, but it’s difficult to identify situations that may require intervention.

Nearly 80 percent of students who took the survey reported not having done anything after watching a person head into a sexual encounter. In most cases, this is not a cause for concern — but there are times when heading back to an empty room isn’t so harmless.

What appears benign may not always be consensual. Bystanders exist in a grey area — it’s hard to act when you don’t know the people involved or the details of the situation.

“I think that part of what happens when you’re at a party and you see someone, who’s a little drunk maybe, making out with someone else, who’s also maybe a little drunk, it’s hard to tell there’s something bad going on initially,” Fuchs said.

To instruct students in deducing dangerous situations, Carnegie Mellon University has designed a game that simulates real life scenarios.

“We gave them answers about how they would intervene. Would you do nothing, would you get another person, do you wait to talk to someone?” said Jess Klein, coordinator of Gender Programs and Sexual Violence Prevention at CMU.

According to Klein, there are multiple reasons people may not intervene.

“It can be anything from not thinking it’s their business or that they have a place in that or not understanding the situation,” Klein said. “People can even talk themselves out of thinking they understand it. There’s the fear of being an outcast, simply not knowing what to do and personal safety.”

Intervention doesn’t come with a manual — it’s hard to know how to define your role as the intervener.

“The purpose of the game was to teach yourself how you would respond in situations where intervention is really clouded — you know something’s going on but you don’t know what to do or intervene.” Klein said.

One in every five women and one in every 16 men will be sexually assaulted while in college. According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report released in 2013, there has only been a surge in sex crimes on college campuses.

Bystander intervention can end potential assault before it happens — and communication is the first step toward increased intervention.

“I think having conversations within your friend group on how to intervene and what a compromising situation at a party may look like is most important,” Klein said. “Maybe you don’t know what to do, communicate it to someone else. If the time calls for it, call the police. You have options.”

A conversation can’t start, however, without awareness — of responsibilities, situations and acceptable actions.

“I think college kids in particular need permission to look out for each other,” Fuchs said. “I think college kids should start talking about the issue, that’s step one.”

Following independent survey results, CMU planned three campus town hall meetings — closed to outsiders — that the university hopes will promote a dialogue among students.

To supplement communication with friends, Pitt carries two student organizations that focus on bystander intervention — RAVE (Raise Awareness and Victim Empowerment) and PantherWELL. Between the groups, 75 trained peer educators aim to provide students with the skills necessary to safely intervene in the event of sexual or domestic violence.

“See something, say something” — prior to speaking with Fuchs, this was my overused mantra. Despite knowing what the bystander effect was, I remained a person in the crowd who would turn a blind eye.

Fuch’s experience was painful and haunting, for her and her bystanders. Fuch’s memories aren’t shadows of isolated events. They’re real, constant occurrences, and they’re preventable.

If I only remained aware of my surroundings and communicated with friends, I could — when the day comes — be the person in the crowd who steps up and helps a person in need.

Marlo Safi primarily writes about public policy and politics for The Pitt News.

Write to Marlo at [email protected]