For a change of pace, give comic books as try

August 18, 2013

For many book lovers, the beginning of the fall semester is a time to wave goodbye to those blissful summer afternoons spent lounging in the sunlight with an engaging book in one hand and a cool drink in the other.

When juggling the stress of classes, clubs, work and play, it’s difficult to find the time or the energy necessary to make sense of Faulkner’s lengthy accounts of the people residing in Yoknapatawpha County. Hell, even something as readily digestible as a Raymond Chandler novel can become a tedious exercise when you’ve just finished slogging through 50 pages of David Hume or if there’s a lab report pending.

This creates a downward spiral of sorts: Those of us who rely on reading as a much-needed escape from the anxieties of college life are often too tired to read, leaving us even more stressed and exhausted than ever. Before turning to a Netflix binge as an alternative, however, students should consider giving comics a try.

It’s easy to scoff at the suggestion. Over the past several decades, comics have been viewed as a medium fit primarily for two groups: children and geeky, twenty-sided-dice wielding, LARP-happy man-children. Setting aside our societal tendency to take shots at that which is sometimes referred to as “geek culture,” there are dozens of comics out there that offer all the nuances and rich characterization of an engaging novel, and not all of them involve spandex suits.

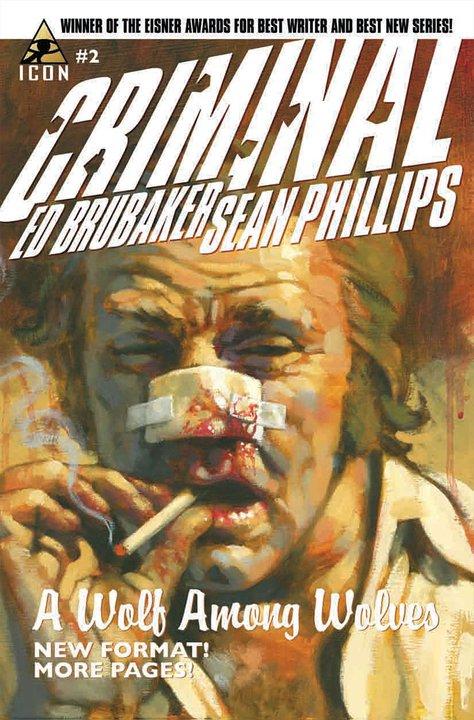

Take Sean Phillips’ and Ed Brubaker’s “Criminal” series of comics. Each chapter focuses on the story of a single character within a city’s seedy underworld as he or she seeks wealth, vengeance or simply to stay alive, often at the cost of others. The stories are steeped in the traditions of classic crime novels, and the characters are nearly as appealing as they are despicable. It’s suspenseful, gripping and pulpy, without a superpower in sight. Best of all, because each story takes about a half hour to read, it isn’t the same sort of heavy commitment as a 200-page novel.

There are dozens more comics that bring different kinds of perspectives and approaches to the genre.

The “Scott Pilgrim” series, drawn and written by Bryan Lee O’Malley, is fundamentally a love story with a hilarious, arcade game-based twist. “Y: The Last Man,” by Pia Guerra and Brian K. Vaughan, imagines a world in which all but one of the world’s men have been wiped out. The creators use this premise as a jumping-off point for a sweeping journey across the globe that often turns gender norms on their head and approaches our own culture’s gender disparities without any traces of preachiness.

Other series, such as Brian Wood’s “DMZ,” approach the escalating tensions between a cohesive surveillance state and libertarian fanaticism in a way that admonishes the radicalism of both philosophies.

Comic book culture is not without its flaws, of course. Thanks to the medium’s historically male readership, one is hard-pressed to find a nuanced female protagonist or even a woman drawn with anatomical accuracy in most of the more popular monthly and weekly comics. “Y: The Last Man,” for example, focuses on the single man on earth and not the more than 3 billion women surrounding him. Additionally, extreme violence is to be expected on a scale that even the trashiest horror movies sometimes fail to match.

There is also still a glut of supernatural and superhero themes, making the genre options fairly limited when compared to fiction or film. This is partially because of the fairly limited audience and partially because of the traditions of the genre. All of the drama of a comic is usually wrapped in these conventional formulas involving heroes and villains with otherworldly abilities, making it difficult to find a comic book equivalent of “Anna Karenina.”

That’s not to say there aren’t comics that defy all of the aforementioned stereotypes.

The award-winning “Persepolis” by Marjane Satrapi is a captivating memoir about growing up during the Iranian Revolution and subsequent Iran-Iraq War. The extremely funny memoirist and novelist Jonathan Ames teamed up with artist Dean Haspiel to create a graphic novel that documented his struggles with alcoholism in a way that was far more tragic than any of the stories he has ever written. While it takes some digging, it is possible to find alluring comics that leave many of the medium’s perceived issues behind.

If nothing else, it’s a medium that deserves a chance. Its limits are being tested almost constantly by writers such as Brubaker, Wood and Vaughan, and the use of beautiful visuals and clever dialogue make the best written comics less work and often more fun than a popular novel. Issues of racism, gender, class and religion are approached in a way that, if not always tactful, can be shockingly complex to a new reader.

And even if the medium still doesn’t have the diversity of voices it needs to appeal to you, it probably beats studying.