In a 2015 speech abroad, First Lady Michelle Obama urged a room full of people not to leave education out of discussions about women’s rights.

“If we truly want to get girls into our classrooms, then we need to have an honest conversation about how we view and treat women in our societies,” she said.

Obama was speaking from Qatar, where nearly 96 percent of women seek opportunities in higher education, according to UNICEF — a statistic slightly higher than in the United States.

In both countries, women outnumber men in secondary education. According to U.S. Census Bureau data collected in 2015, more women than men in the United States were likely to have bachelor’s degrees for the first time in recorded Census Bureau history.

Across the country, conversations about the rights of women have expanded to include sexual assault, pay discrimination and gendered violence.

Worldwide, many women still aren’t granted the opportunity to get a basic education, and it was not long ago that women in the United States were excluded from the hallowed halls of secondary education.

From 1787 to 1895, Pitt was exclusively male, and in 1914, women made up just over 25 percent of Pitt’s population — about 15 years earlier, there were no female students on campus.

Today, women make up about 4 percent more of the student body than men, according to Pitt’s 2016 Fact Book. In the fall 2015 term, 14,948 female students and 13,701 male students were enrolled at Pitt. Women make up about 40 percent of Pitt’s 4,143 faculty members.

Irene Frieze, one of the original faculty members of what is now the gender, sexuality and women’s studies program at Pitt, said even in just the past few years, the University has changed for women.

“I think it reflects the society,” Frieze said. “Some of the things that have happened in the last five years, we couldn’t have imagined happening 20 years ago.”

More than 10 years ago, on Pitt’s bicentennial anniversary, the Office of the Provost launched a project to document and celebrate the history of women at Pitt.

“Pitt has progressed in step with national conversation about gender, sexuality and women,” said Maurice Greenwald, another original faculty member in the GSWS program. “It has embraced the challenge of diversifying the composition of its administrators, faculty and students.”

The information below, except for interviews, is based on information found in the University’s History of Women at Pitt Project.

Pitt’s First Women: 1895 – 1938

In the 1700s, education for women was geared solely towards “womanly duties,” having to do with homemaking — highly educated women were considered unusual.

Colleges for women appeared only in the mid-1800s. While some aimed to equip women with the same level of education their male counterparts received, most schools’ curriculums remained conservative.

Until the end of the 19th century, some people still believed that intellectual work for women might have adverse physical consequences, but in the 1890s, enough college women survived the experience to dispel those fears.

Pitt was founded in 1787 as an all-male school. Its first female students were sisters, Margaret and Stella Stein, who entered in 1895 as sophomores after completing their first-year coursework at Pittsburgh’s Central High School.

The sisters studied math, astronomy and surveying and ended up tying for valedictorian. They were also the first women to receive Master’s degrees from Pitt in 1901.

As Pitt began to admit more women, the University saw increased enrollment in the liberal arts.

In 1910, when Pitt established the School of Education, the number of female students jumped from 30 to about 400. By 1914, 600 women were enrolled at Pitt, making up more than 25 percent of the student population.

An increasing number of female students started forming exclusive clubs. The first sorority, Pi Theta Nu, was established in 1908.

The first woman of color at Pitt was Jean Hamilton Walls. She received bachelor’s degrees in math and physics in 1910. In 1938, she became the first black woman to receive a Ph.D. at Pitt.

Adrienne Washington became the first African Americans student — of any gender — to earn a PhD in linguistics at Pitt in May 2016.

Women on Staff:

Pitt hired the first female faculty member, Blossom Henry, in 1918 to teach modern languages.

According to the Pitt history project, when a reporter asked Henry what she thought of the campus, she said it was “full of men.”

After World War I, female students demanded that Chancellor Samuel McCormick hire a Dean of Women. Thyrsa Wealhtheow Amos, from the psychology department at the University of Kansas, took the role in 1919.

She encouraged the formation of more social clubs for women, as Amos said activities “for women only” would provide more opportunities for female leadership. Under her tutelage, the Women’s Self-Government Association, the Girl’s Glee Club and QUAX, an honorary science club, were founded.

In fact, Dean Amos created Pitt’s famous Lantern Night in 1920. It was supposed to be a “sensible” alternative to the hazing associated with fraternities.

In 1968, the Dean of Men and Dean of Women positions were combined to form the position of Dean of Students.

New Women-Centered Programs at Pitt: early 1970s

According to the History of Women at Pitt project, in the early 1970s, there was an all-time high of 40 percent female undergraduates at Pitt, but there was a pronounced male influence on campus.

Graduate and professional schools had a male majority, and men occupied most of the administrative positions on campus. Women were generally excluded from leadership roles.

Chancellor Wesley Posvar created the Advisory Committee on Women’s Opportunities in the spring 1970. The ACWO helped address goals of the newly formed University Committee for Women’s Rights and provided advice throughout their processes.

The ACWO helped establish the Women’s Center in 1973 and the women’s studies program in 1972.

The Campus Women’s Center became the Oakland Women’s Center in 1982, ending its affiliation with Pitt.

But the women’s studies program has grown. It began with three part-time positions: psychology professor Irene Frieze, history professor Maurine Greenwald and English professor Marianne Novy.

“We had to figure out how to set up a new program from scratch,” Frieze said.

According to Frieze, the women’s studies program had difficulty filling classes in its early days in contrast to the high student demand for gender, sexuality and women’s studies classes at Pitt in the present.

According to Greenwald, social movements — like the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment — garnered more attention for the program.

“I would say that the program grew over time in accordance with the mushrooming of women’s involvement in social movements and women academics’ persistence in legitimizing the new multidisciplinary field,” Greenwald said.

The program was given a “modest” budget for operating because the expectation was that interested faculty would develop the curriculum, Greenwald said.

“[Women’s studies] in its early years had to prove its academic worth to the University,” Greenwald said. “It would take many years before the study of women gained academic respectability and legitimacy.”

According to Frieze, the mostly male faculty was a bit skeptical of the program at the time.

“We had to kind of make sure that people took us seriously,” Frieze said.

The women’s studies program expanded its scope and changed its name to gender, sexuality and women’s studies in 2014. The GSWS program became a major in the fall of 2015.

Pitt Women in the Present: Looking Forward

Today, women like the Stein sisters, Walls, Frieze and Greenwald pass the proverbial lantern onto millennial women — many of whom have established student organizations dedicated to women’s rights and gender equality.

As the conversation moves away from just getting women onto college campuses, Sarah Best, the current president of the American Association of University Women, said it’s shifting toward issues like rape culture and transgender rights.

“I would say on campus, we still really need to work on the sexual assault epidemic and the way universities deal with the issue,” Best said. “I also think at Pitt and on other campuses, we really need to recognize and respect trans[gender] people.”

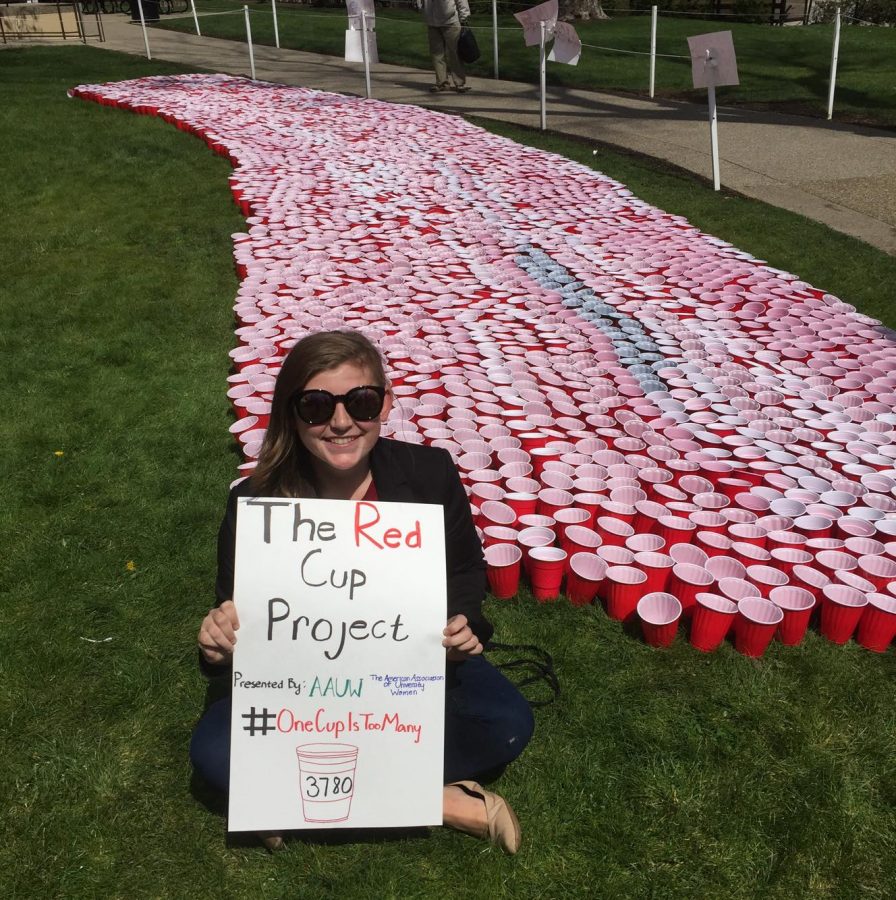

AAUW Pitt’s biggest project to date was the Red Cup Project, where club members used solo cups to visualize national statistics regarding sexual abuse on college campuses. In the future, club members hope to take on projects concerning body positivity and female leadership.

Greenwald, looking back at the history of women at Pitt, said the resilience of women-centered programs shows that gender and sexuality studies is not a passing trend, but a legitimate part of academia.

“In the 1970s, a dean of Arts and Sciences asked the women’s studies core faculty how long it might take for the program to put itself out of business,” Greenwald said. “The past 40 years have clearly demonstrated the vitality and importance of women’s studies at Pitt and elsewhere.”