I’m optimistic about Pitt declaring the coming year the “Year of Diversity,” but I can’t help wishing for more.

I wish I didn’t feel the need to defend my own merits when affirmative action gets questioned. I wish minority voices didn’t have to spring to the offensive whenever the issue of race is raised. I wish we lived in a country that truly values equality — where everyone is worthy unless proven otherwise.

But this is the reality of living in the United States today — a country that sees race before attributes. And when it comes to the pillars of opportunity — college campuses — the underlying narrative is hardly subtle.

So when the University saw me, an African immigrant attending Pitt on a full-tuition scholarship, it couldn’t ignore the whispering murmur of stereotypes and assumptions.

And neither could I.

Until achievement can be acceptable at face value, affirmative action will fail — even when it succeeds. Whenever a minority who has shoved aside centuries of institutionalized racism to excel is still forced to question their merits, diversity and equal opportunities remain rooted in dreams of a better future.

Affirmative action has only one goal — diversity.

In early June, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld affirmative action in Fisher v. University of Texas in recognition of that goal. The case, brought by Abigail Fisher, a white woman who claimed she was denied acceptance to the University of Texas because of her race, attacked the University of Texas’ Top 10 Percent program. Automatically accepting Texas students in the top ranks of their high school, the program opens the remaining admission slots to holistic review — including the recognition of race.

In a victorious end to an eight-year legislative battle, Justices supported the University of Texas’ race-conscious admissions program in a 4-to-3 vote. Drafting the majority opinion, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote, “Considerable deference is owed to a university in defining those intangible characteristics, like student body diversity, that are central to its identity and educational mission.”

But the University of Texas is not the only university taking measures to enrich their curriculum — and Fisher is not the only applicant with delusions of entitlement. Although the Supreme Court cemented affirmative action’s place on our campuses, it remains cast in shadows of contempt.

And it’s not isolated to the notorious conservative stance. I feel that contempt every time I hear self-described liberal peers boast their high school records and end with shock that they didn’t receive more for their efforts. I feel that contempt whenever I speak with friends about our enrollment at Pitt in uncomfortable tension, as I sense their belief that my race was the biggest factor in my experience. And I feel it most whenever I sit in a room of talented peers and wonder, “Why me?” and a voice in my head responds, “Because you’re black.”

Because I’m more than black, or African or an immigrant. I am a person who achieved a goal whose success is being reduced and degraded to the realms of my race.

Affirmative action didn’t do that.

The culprit has always been the public smear campaign aimed at delegitimizing and devaluing the practice — an effort that didn’t begin or end with Fisher’s tirade of privilege. But when you strip away the racist veneer surrounding opposition to affirmative action, all that’s left is false impressions.

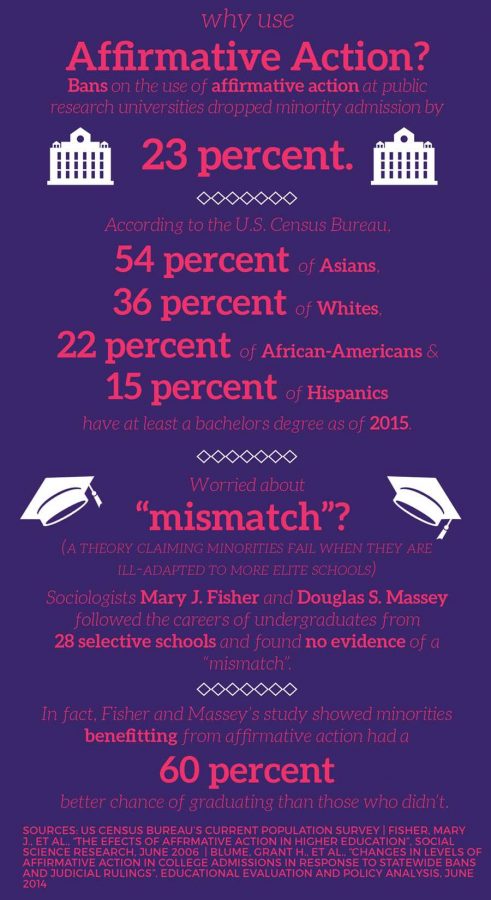

Researchers have disproved the “mismatch” theory — the notion which claims minorities fail when they are ill-adapted to more elite schools. In a 2006 study, sociologists Mary J. Fischer and Douglas S. Massey followed the careers of undergraduates from 28 selective schools and found no evidence of a “mismatch.”

“If anything, minority students who benefited from affirmative action earned higher grades and left school at lower rates than others,” they concluded.

Sociologists Sigal Alon and Marta Tienda also found minority students at more selective schools were more likely to graduate than those elsewhere, as did Harvard professors Mario L. Small and Christopher Winship.

When analyzing the same dataset, Maria Abascal and Delia Baldassarri found disadvantage was the cause of distrust, disproving political scientist Robert D. Putnam’s study linking diversity to lower levels of trust and civic and political participation.

Those claiming affirmative action unfairly benefits minorities also fail to acknowledge only 22 percent of African-Americans and 15 percent of Hispanics held at least a bachelor’s degree in 2015, as opposed to 36 percent of Whites and 54 percent of Asians, according to the United States Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey data.

Affirmative action serves as an equalizer — and that includes economic opportunity. With the current unemployment rate for African-Americans at 8.4 percent — nearly twice the rate for Whites at 4.3 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics — affirmative action should be a key component of our never-ending initiative to decrease the unemployment rate. Calls to focus on socioeconomic status in admissions overlook the reality of race and economics being entangled in the pursuit of educational diversity.

But the fundamental fact of the issue — as most universities have discovered — is that there is really no way to achieve diversity and increase minority admissions without incorporating affirmative action. A 2013 study by Grant H. Blume and Mark C. Long of the University of Washington found bans on the use of affirmative action at public research universities dropped minority admission by 23 percent when compared to a one percent drop in states without bans.

For those reasons, and countless more, schools have not shied away from using affirmative action — in fact, many have worked to amplify and exhibit their efforts. In 2015, Pitt created the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, published their affirmative action initiatives and highlighted diversity and inclusion as University values.

The University’s effort is not only admirable — it is necessary. Two years ago, I wrote a column looking at diversity at Pitt. At the time, about 72 percent of Pitt’s entire student body was White. Today, that demographic has gradually diminished to about 70 percent. Pitt has always had difficulty achieving diversity, but its recent initiatives should be applauded — as evidence of the University working to enrich their students’ education and address historical shortcomings.

I became aware of these initiatives a year ago, when the scholarship I received was renamed a “Diversity Award” from the inconspicuous “University Scholarship” that had formerly been listed on my financial aid page. Rather than glossing over the change, I grappled with internal turmoil. I could no longer think about affirmative action from a position of comfortable indifference. I was intimately connected.

It’s not like I didn’t know affirmative action had a role in my admission to Pitt. Because my immigration status of asylee at the time of enrollment made me ineligible for the majority of alternative financial aid options — including Pitt’s other scholarships — I always knew it was tied to my experience.

But the evidence forced me to contemplate my reality with affirmative action. Where did I fit into the contention and debate? Was I inferior? Did I truly belong here? The thoughts that ran through my head were shaped by the judgements I perceived — that minorities were less than, ill-equipped and ill-adapted.

As a country, we shouldn’t accommodate disparagement under the veil of meaningful debate, forcing minority students to carry enormous burdens as part of their educational experience.

My new wish is for that burden to soon be lifted.

Bethel Habte is a Senior Columnist at The Pitt News who primarily writes about social issues and current events. Write to Bethel at [email protected].