The only topic political people in 2016 seem interested in discussing is the presidential election. But while the decisions in November are of undeniable consequence, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton’s agendas shouldn’t be the only ones on display.

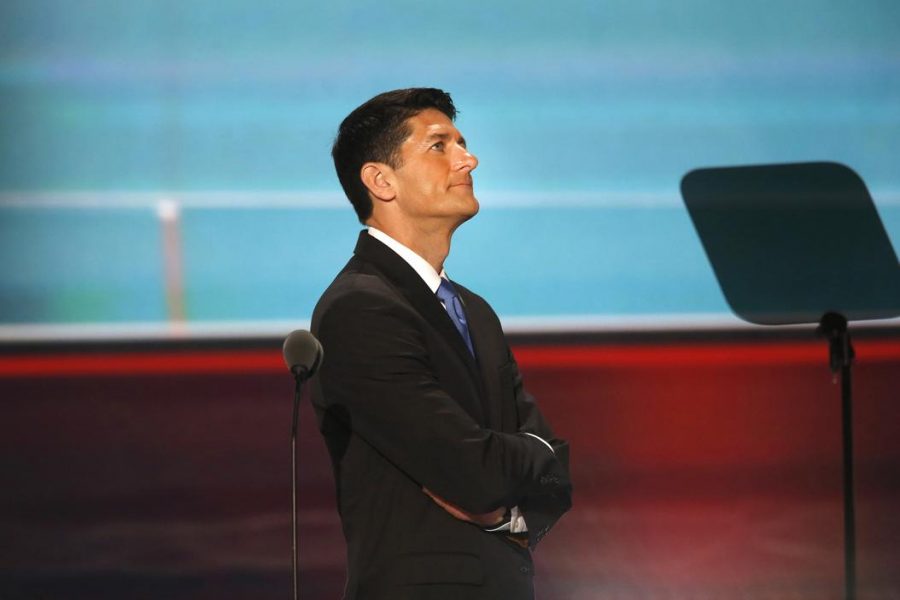

Since taking the speakership last October, House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) has worked closely with leaders in Washington, D.C., such as Budget Chairman Tom Price and House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady and beyond to outline a fresh approach to combatting poverty in the 21st century. For those working to alleviate the suffering of our nation’s poor, Ryan’s plan, “A Better Way” should take center stage and garner our attention and support.

Ryan’s platform calls for the end of an era in which each political party’s commitment to the “war on poverty” is measured by good intentions, money spent and quantity of government programs created. In the 21st century, we must demand empirically sound anti-poverty policies and results through fresh policymaking that promotes work and dignity. Ryan’s plan is it.

At the onset of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty in 1966, the national poverty rate was 14.7 percent. Fast-forward half a century and tack on $15 trillion in governmental support spending, and that rate had fallen to just 14.5 percent in 2013. A year later, the rate had risen to 14.8 percent — higher than it was in 1966. An American raised in poverty today is no more likely to rise out of it than they were fifty years ago, a reality affirmed and verified by researchers at Harvard, Berkeley and the U.S. Treasury Department. This lackluster performance would not be acceptable in any other societal realm or venture. So why are we tolerating it in our fight against poverty?

As a strong foundation for his alternative approach, Ryan’s proposals stress the inherent value of work and dignity, linking benefits to the pursuit of skills that lead to permanent employment. We cannot continue to rely on a system that has the potential to limit work in the face of assistance through welfare cliffs that can disincentivize upward employment mobility.

Before we can adequately debate any specific policies, we must comprehend the necessity of this shift in principles. Ryan’s plan is as broad as poverty is complex, but the goal is clear: Give Americans hope and provide confidence in the process.

There are obvious reasons to promote full-time work, a key to Ryan’s plan, as a counter to long-term poverty. Of those Americans living in poverty, two-thirds do not experience full-time employment, while only 2.7 percent of those who do experience poverty. Yet proposals stressing employment as an essential means of fighting poverty, such as work requirements for able-bodied welfare recipients, become partisan issues — such as when Democrats accuse Republicans of being insensitive to the needs of the poor, or, more commonly, just in favor of the rich.

To know real progress in the war on poverty, we must move past this. Even the Brookings Institution, a liberal-leaning think tank, emphasized in 2013 that obtaining and sustaining full-time employment is one of three essential tasks of getting and staying out of poverty.

Going forward, government policy must then abandon a system that prioritizes dependency and punishes employment mobility. Working with a Republican Congress in 1996, Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act — better known as Welfare Reform. One of the act’s chief goals was to reduce dependency and foster greater employment opportunities. It worked. In the years immediately following reform, single mother employment rates rose considerably. According to the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, between 1996 and 2000 the employment rate for never-married mothers jumped from 63 percent to 76 percent. In turn, child poverty rates dropped to unprecedented levels. In particular, black communities benefited as the poverty rate for black children dropped from 41.5 percent to 30 percent. For those who would dismiss these achievements as the byproduct of a good economy alone, little evidence can be found.

Child poverty rates had hardly moved during the 25 years prior to reform. It is difficult to reason fairly that the strides made immediately after reform’s emphasis on employment were mere happenstance.

But in July 2012, the Obama administration, through bureaucratic fiat, allowed states to waive work requirements put in place during the era of reform. The administration sought to grant states, despite the congressional statutes of the reform era, the ability to change work requirements administratively. While an easing of federal regulatory mandates is crucial to 21st century anti-poverty success, an emphasis on work and dignity must remain a national priority. Ryan’s platform calls for a clear return to and continuation of policies that reward employment seekers for those able to work.

Moreover, Ryan’s platform addresses the inconvenient truth that in practice, our current approach to allocating welfare benefits can hinder employment mobility for low-income families. For instance, because of taxes and the current structure of welfare payments, a single mother with two children making minimum wage in Pennsylvania would be worse off financially if she obtained a job or earned a raise paying her $10.35 per hour than if she applied for welfare support, according to the Congressional Research Service.

To protect those most in need from this welfare cliff, Ryan’s agenda calls for greater state flexibility to customize packages for citizens. Doing so would ensure that mobility at work is never a punishable offense. Accomplishing this through clunky federal bureaucracy is simply impractical.

Another key component to incentivizing work without dismantling crucial benefits is the promotion and expansion of the earned income tax credit, a refundable credit available to low-income workers. The EITC would act as a supplement to income from work, thus easing anxieties about potential loss of benefits from a raise or new job. For those experiencing difficult times and yearning to get back on their feet, the EITC provides financial assistance and actively encourages work, a boost on both a quantitative and qualitative level.

If we as Americans are serious about successfully combatting poverty more than we did over the past fifty years, we can no longer remain complacent and accept the conventional remedies of the past. We must accept that there’s a better way. By moving toward Ryan’s proposed path, we may confidently assert that regardless of starting point, America’s promise of hope and social mobility can ring true for all.

Matt is the former Opinions Editor of The Pitt News, a 2016 Pennsylvania Finnegan Fellow and a member of Pitt’s Student Conduct Peer Review Board. Write to him at [email protected].