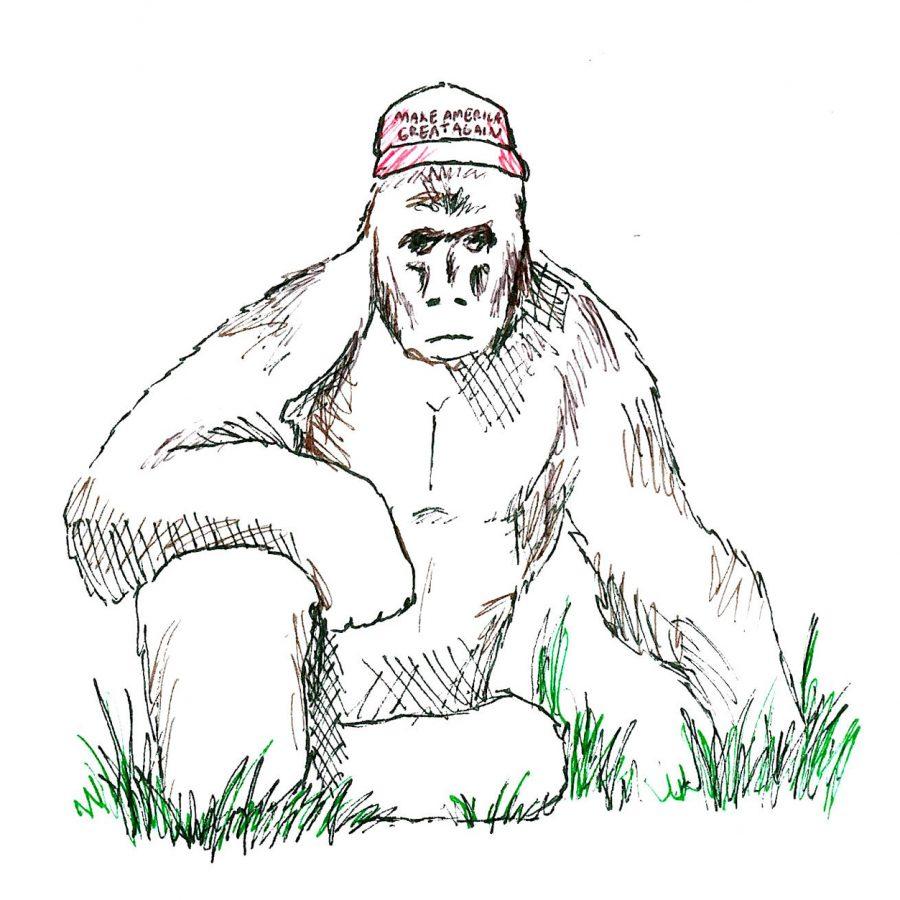

Of all the stories shaping the cultural landscape this summer, two events from May have consistently broken the internet. One involves an unpredictable creature with primate ancestry — the other is Harambe.

On May 26, reality TV personality Donald Trump received his 1,237th delegate to the Republican Convention from North Dakota, and with it the title, bestowed by the Associated Press, of presumptive Republican nominee for president.

Two days later, on May 28, a three-year-old at the Cincinnati Zoo fell into the enclosure of a rare silverback gorilla named Harambe, prompting zoo officials to shoot and kill the animal in order to protect the child.

Each of these horrific events prompted extensive controversy, especially on social media. Harambe-themed memes blanketed the internet, resurging in popularity last month and showing no signs of disappearing. Of these stories, the Trump phenomenon clearly carries more long-lasting consequences. But the absurdist humor that gave Harambe memes longevity presents a clue to the Trump campaign’s continued success: At this point, we’re just tired of being outraged.

“Outrage fatigue” sounds like a fake condition — it’s been reported on by, among other outlets, the Onion — and it’s unlikely to earn classification as a medical condition anytime soon. Nevertheless, it’s a phenomenon that academics, including digital anthropologist Rahaf Harfoush of Duke University, have attempted to explore.

“Eventually you start hearing the same piece of sad news over and over that it loses its ability to pull you, and that is really dangerous,” Harfoush commented at a Duke-hosted panel in February.

Of course, the ability to become desensitized to shocking news has existed ever since there was news to report. Left-leaning journalist David Roberts described the string of controversial actions taken by the Bush Administration in 2003 related to the invasion of Iraq as “difficult for media to cover,” due to the sheer number of stories.

But the numbing process becomes much quicker in the presence of what Harfoush calls “an ecosystem of an infinite amount of information” — in other words, social media. Social media activism has the potential to spread awareness of important issues but runs the risk of making people feel over-informed.

Nowhere were the dulling effects of information saturation more stereotypically obvious than in the social-media-fueled reactions to Harambe’s death. By the beginning of June, a petition online at Change.org had collected over 400,000 signatures demanding “justice for Harambe.” It’s difficult to remember, but at one point discussion about the gorilla’s death was mostly un-ironic — ranging from questions about perceived racism in the rush to condemn the child’s black parents, to the morals of keeping wild animals locked up in zoos in the first place.

Whether or not these conversations are appropriate, our ability to have them has long since disappeared. The level of self-righteous over-reaction was too much for the internet to handle and spun into the hyper-sarcastic memes that have dominated internet culture for a surprisingly long stretch. Anger at Harambe’s death was so tiring that, in an absurd way, it became funny.

Besides killing off a meme that’s past its prime, what’s the purpose of analyzing Harambe’s death and viral resurrection? The same fatigue that somehow makes a dead gorilla funny also makes shockingly dangerous candidates like Trump more palatable. One joke is amusing, the other has a very real chance of becoming president of the United States.

Trump’s campaign, both before and after he clinched his party’s nomination, has been a parade of the outrageous and the absurd — from the candidate’s infamous claims bashing Mexican immigrants to his primary debate clash over the size of his hands. There are so many stories about Trump making supposedly irreversible gaffes in the past 14 months or so, it can be hard to remember any single one of them in particular.

Anyone remember the unprecedented and very public feud between the GOP’s presidential candidate and Pope Francis? Probably not, and I can’t blame you — Trump has saturated us.

Pushing for voter forgetfulness isn’t an accidental component in the Republican Party’s national strategy this fall — outrage fatigue is a fundamental element of the effort to elect Trump. In an interview with Fox News Sunday’s Chris Wallace, RNC Chair Reince Priebus suggested “that all these stories that come out — and they come out every couple weeks — people just don’t care.”

Trump’s candidacy for president is on the same level of seriousness as a meme. An avalanche of pleas from the likes of the Washington Post, the New Republic and even the New York Daily News has begged readers to stop considering Trump a joke candidate — and, indeed, a Republican presidential victory in November would be anything but funny for millions of Americans who belong to imperiled minorities.

The issue isn’t getting serious about the threat the GOP candidate poses, so much as staying serious for a sustained period of time.

Remaining focused in the face of so much farcical news is a tall order. You don’t do it the way Green Party presidential nominee Jill Stein has been attempting to re-infuse the Harambe discourse with sincerity — tweeting last week about the gorilla’s “catastrophic” death. Self-righteous lecturing only feeds into the phenomenon, be it Harambe or Trump.

Trump and his candidacy are prime material for ironic internet humor. If we want to maintain important discussions about the candidate without going the way of Harambe, it’s important to recognize the absurdity while continuing to point out the high stakes of a Trump victory. We have to foster a conversation that balances the two — the intensely serious and the overwhelmingly ridiculous. You can only denounce somebody as a fascist so many times, and Trump’s absurdist campaign thrives on the constant flow of stories that obscure each other in the end.

Instead of trying to cover every offensive word coming from Trump’s mouth, media attention should focus on substantive analysis of the worst things he’s said and done.

Media filters are supposed to separate out the bait — right now, it’s too busy chasing it. And if that doesn’t change soon, we might end up spending four years with a meme as president.

Henry primarily writes about government and domestic policy for The Pitt News. Write to Henry at [email protected].