Sam Gottesman, a Holocaust survivor, still remembers his near-death experience 71 years ago.

Gottesman, originally from former Czechoslovakia, said that at one of the many concentration camps he was placed in, he found himself on the list of children who were to be shipped back to Auschwitz to become factory laborers. He later realized that going back to Auschwitz would likely lead to his extermination. To avoid the potential death sentence, Gottesman marched to the S.S. officer’s door and requested to have his name taken off the list, citing his age of 21 years old as his main defense.

He was reprimanded twice and forced to strip naked, but the officer scratched his number — 37502 — off the list.

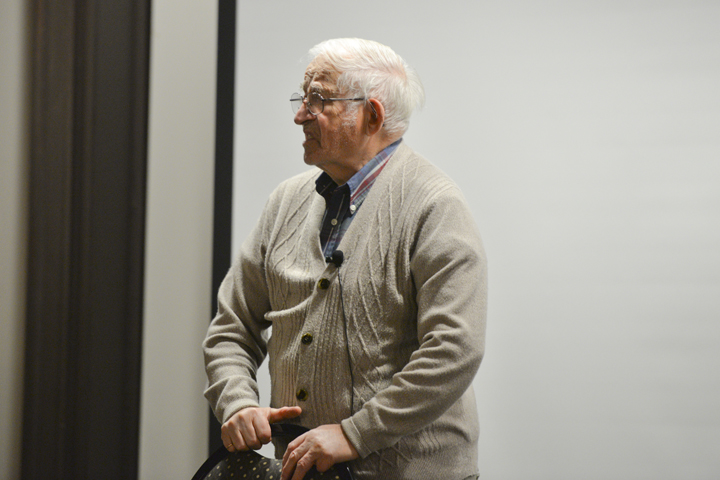

Gottesman still tells his story, mainly to high school students, to educate people about one of the most deadly and despicable events of the 20th century and to remind them not to forget the dangerous lessons of the past. In front of a packed crowd at the O’Hara Student Center, he spoke to 110 students and faculty, methodically reliving every detail through his heavy Central European accent.

Alpha Epsilon Pi, a Jewish fraternity on campus, hosted the talk as part of its philanthropic goal to raise money for the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh. The Philanthropy Chair of AEPi, Seth Appel, said the event was especially poignant less than a week after the anniversary of Kristallnacht — when Nazis in Germany torched and vandalized Jewish homes, schools and businesses.

Born in 1923, Gottesman was 15 years old when Nazi Germany invaded his home country, and he immediately felt the impact of the anti-Semitic regime. The Nazi government first enacted “the Jewish Laws,” a colloquial name for a different set of laws Jews lived under in Nazi-controlled lands in the 1930s.

Gottesman drew laughs from the mostly somber crowd when he gave a surprising description of the intimidating Nazi officer that eventually saved him from Auschwitz.

“I was lucky enough that the second-in-command was what we’d say is a ‘mensch.’”

In Yiddish, a mensch translates to a “good person.”

Gottesman’s humor came as a surprise to some in the audience, as Holocaust survivors are understandably solemn when reliving the terrors of their childhoods in Europe. Sophomore Alyssa Berman, who is double majoring in political science and Jewish studies, was shocked at his lightheartedness.

“I really liked that he was cracking jokes at the end. I’ve never really heard a Holocaust speaker who was as friendly and joking as he was. And I guess that’s the part that moved me the most,” Berman said.

In 1943, Gottesman, along with every other Jewish person, had to reapply for citizenship. By April 1944, on the day of Passover, Nazi officers ordered Gottesman and the rest of his small town to be transported to a ghetto. They would later be sent to a concentration camp to either be killed or worked to death. It was not until the spring of 1945 that Allied forces liberated Gottesman.

Gottesman was constantly being uprooted to different camps, each with their own atrocities and painful memories.

He recalled asking where all the women were on his first day at Auschwitz. Another prisoner pointed to a chimney to answer Gottesman’s question. Later, on his first day at Bergen Belsen concentration camp, he realized that the situation could somehow be even more dire.

“There were dead bodies all over the place,” he said. “They could not even keep up picking up and doing away with the dead bodies. It was an awful camp.”

Near the tail end of his talk, Gottesman admitted that he had not told his son that he was a Holocaust survivor until his son asked him about it while in college.

Ethan Silver, a member of the AEPi fraternity, related to that detail specifically. When he was in third grade, both he and his mother found out that his grandfather had been in the Holocaust.

“I don’t think I really understood it,” Silver said. “I wrote a report about it, so I understand he went through a lot. I was the same age, when he told me, that he was when he went through [the Holocaust].”

Silver was struck by the drastic differences between his and his grandfather’s life experiences, just as Gottesman’s memories of being a young adult contrasted with the audience of college students seated in front of him Monday.

“He would tell me stories about him sleeping in a barn one day and then in the middle of the snow, the next,” he said. “And I was like, ‘I’ve been in a home every day I’ve been alive.’”

Speaking to a crowd of many Jewish individuals, Gottesman touched on how the Holocaust affected his faith in God. During the war, he said prayers on his way to his labor assignments. It was after the war when Gottesman began to lose faith in God and Judaism.

“I had a bone to pick with God,” he said.