Most English teachers — and certainly any editor — will say to use the active voice when possible. Jackson Katz, an educator and author at the forefront of the male feminism movement, wants to make sure you remember that too.

“We talk about how many women were raped last year, not about how many men raped women,” he said, according to a screenshot that went viral in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein scandal. “So you can see how the use of the passive voice has a political effect. [It] shifts the focus off of men and boys and onto girls and women.”

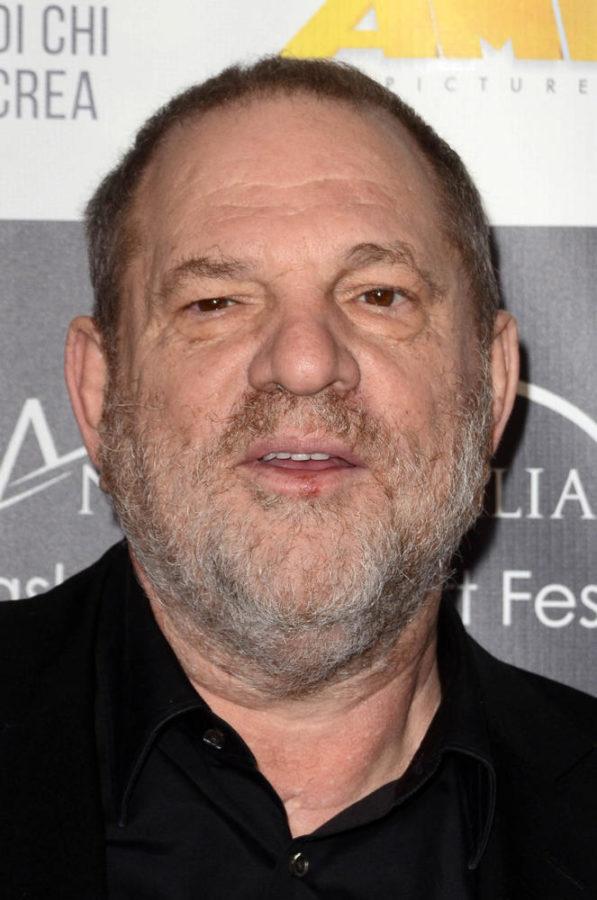

In an interview with Fortune on Wednesday, he said the quote came from a 2012 speech at Middlebury College. But it suddenly became relevant when The New Yorker and The New York Times released groundbreaking reports earlier this month detailing numerous accusations of sexual harassment and assault against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein.

The New Yorker piece was published Oct. 10, and included 13 women’s accusations. Now, as CNN reports, that number is more than 40.

In response to these stories, people across the country stood up to tell theirs. The #metoo social media movement is a catalog of women’s stories of sexually assault and harassment, and it empowers women and other survivors to share their stories, should they choose.

But while liberating and empowering, the movement instrumentalizes tales of suffering to further the political goal of ending workplace sexual misconduct. Just like how Katz noted passive language has the power to place ownership for sexual assault on women, the #metoo movement places the burden of proof on women. Instead, men should be the ones taking ownership. We should be discussing the number of men that raped women — or more broadly, people that committed rape — in a certain year, rather than the number of women that were raped.

That’s why some chose to share modified versions of the hashtag, removing the gendered pronouns and including personal takes on why it’s wrong that survivors must share their stories for anything to change. Survivors of sexual assault are rightly standing up to those who try to place the blame for violence on them — but there are ways others can help too.

We have the power to change the conversation surrounding sexual assault and harassment. The issue is incredibly complicated, and made more so by the fact that violent, explicit language can induce panic for survivors. But like Katz suggests, there’s one place we know we can start — using active language.

In the aftermath of the Weinstein scandal, much will change — and hopefully for the better. The National Women’s Law Center told The New York Times they received twice the volume of calls from survivors after the story broke, and the #metoo hashtag was used more than 500,000 times in the first 24 hours.

The change occurring is just the beginning — and now we have the chance to keep changing the conversation for the better.