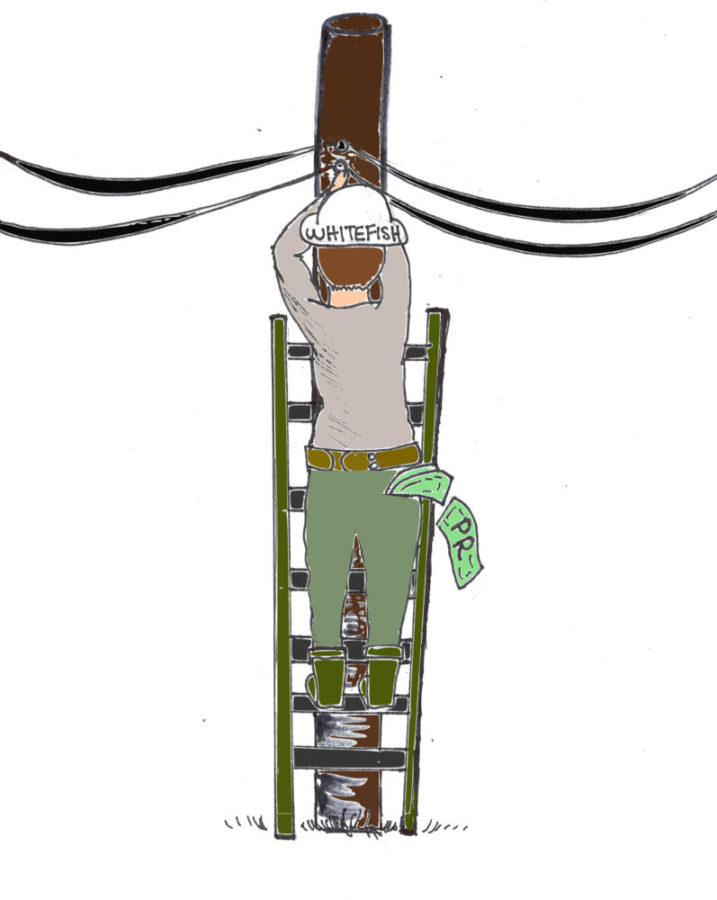

As a small-town business owner, what do you do when a local Facebook friend suddenly becomes Secretary of the Interior? If you happen to live in Whitefish, Montana, you simply wait for the next natural disaster.

Puerto Rico was almost entirely without power after Hurricane Maria devastated the island earlier this fall. The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority awarded a $300 million contract to Whitefish Energy Holdings late last month to rebuild 100 miles of transmission lines the storm had destroyed.

By a strange coincidence, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke and Whitefish are both originally based in the same small Montana town. And that isn’t the only thing that’s hard to believe about Whitefish’s contract. It prohibited government audits of the work or profits and suggested FEMA had already approved the contract.

However, FEMA Administrator Brock Long testified to the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Oct. 31 that his agency was unaware of the contract, and would have been unlikely to have approved it had they seen it.

“No lawyer inside FEMA would ever have agreed to some of the language in that contract,” Long said.

But you don’t need to be a FEMA lawyer to see that Puerto Rico’s contract with Whitefish was a questionable decision. In a congressional hearing Nov. 7, Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., went even further, suggesting the company’s relationship with members of President Donald Trump’s cabinet had a role in awarding of the contract.

“No more sweetheart deals to fly-by-night companies,” Grijalva said. “That needs to stop, and it needs to stop immediately as well.” Whitefish, a small company with little experience, was paid suspiciously well for the work it did.

Whitefish’s qualifications to undertake this large and technically challenging task were few, if any. On the day Maria hit Puerto Rico, the company only had two employees. Whitefish’s basic trucking license had previously been revoked when, according to The Washington Post, they began the process of transporting five helicopters and 2,500 tons of equipment to Puerto Rico.

An Energy Department contract for a small transmission line repair in Arizona in July listed Whitefish as an “economically disadvantaged woman-owned small business,” according to the Post. Amanda Techmanski, a registered nurse and the wife of Whitefish CEO Andrew Techmanski, is listed as the manager. The company address is registered to the couple’s home.

But despite its apparently humble origins in a Montana homestead, Whitefish charged prices that outstripped even those of the biggest world-class contractors. The company’s hourly pay scales were $319 for linemen, and $462 for foremen. Compare this to rates for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers who are doing similar work in Puerto Rico, offering hourly rates of $195 for linemen and $230 for foremen.

So how did PREPA decide to award this overpriced contract to a company with next to no experience or resources for the job? PREPA claims it’s because other companies, wary of the dangers of the island’s financial solvency, asked for a lump sum upfront. This explanation raises nothing but more questions about Whitefish. How could a company with only $1 million in annual revenue afford to risk doing $300 million of work with a bankrupt agency?

While its financial assets aren’t all that impressive, Whitefish does boast connections to the Trump administration and prominent supporters. Ryan Zinke’s son worked at Whitefish for a summer. Lolita Zinke — Ryan’s wife — “likes” Amanda Techmanski photos on Facebook. One of Whitefish’s key financial backers, HBC Holdings, was founded by Joe Colonnetta, who has also donated thousands to Trump and other Republicans.

Although Zinke denied any influence on the awarding of the contract in a tweet Oct. 27, he did acknowledge that he had been in contact with Whitefish. Yet the connections, coincidences and improbabilities make it difficult to believe that the deal was free of corruption.

Controversy around the deal led PREPA to cancel it, though Whitefish has already billed or been paid $20.8 million, according to The New York Times. The work already completed by the company was exceedingly poor — just last Thursday, a power line repaired by Whitefish failed, reducing the number of islanders with electricity from 40 percent to just 18 percent.

In light of the issues with the company, the House Committee on Natural Resources sent a letter to Ricardo Ramos, director of PREPA, questioning the Whitefish contract and requesting documentation of the contract.

“Specifically, the size and terms of the contract, as well as the circumstances surrounding the contract’s formation, raise questions regarding PREPA’s standard contract awarding procedures,” the letter read.

If it’s found that Zinke or others in the Trump administration were complicit in securing government work for hometown friends, it wouldn’t be the first time the federal governrnent was caught picking favorites. Sometimes, like during President Ulysses Grant’s tenure in office, corruption due to favoritism didn’t reflect personal corruption on the part of the president — simply presidential ineptitude. For others, like President Warren Harding, entanglements like the Teapot Dome Scandal demonstrated corruption reaching all the way up to the top.

Of course, it’s uncertain what investigators will find in the documentation of the Whitefish contract. But no outcome will reflect well on President Trump and his administration’s ability to deal with natural disaster relief. At best, it allowed an incompetent organization to take the important role of fixing the island’s electric grid. At the worst, one of its members used a position of influence to provide a friend with a sizeable payoff”.

Either way, one thing’s for sure — in 2017, it pays to be from Whitefish, Montana.

Write to Bianca at [email protected].