If insanity is doing the same thing twice and expecting a different result, then administrators at Pitt must not agree with that definition.

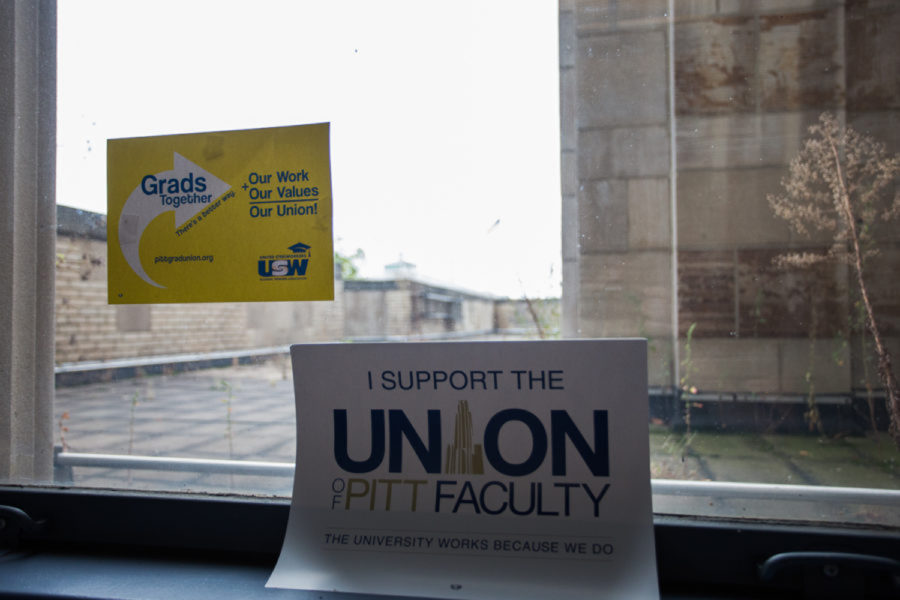

Pitt graduate students engaged in unionization efforts said last week that the school’s administration will challenge a petition to hold an election to decide whether or not to unionize. According to a Facebook post from the group, the University plans to argue that grad students aren’t employees and thus don’t have the right to unionize to the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board.

But that argument isn’t original. Administrators at Penn State used an uncannily similar strategy and argument in an attempt to block an election for a union in State College. And the PLRB announced just last month that Penn State’s argument was insufficient reason to block an election.

“Graduate assistants receive compensation from the University in the form of a stipend, tuition remission, and health care benefits,” the Board’s decision read. “These facts from the record are clear evidence of an employer-employe[e] relationship.”

It appears that the decision in the Penn State case leaves little room for ambiguity. Provided grad students work for their schools either as teaching assistants or in research or administrative roles — as most do — they function as employees and should be allowed to vote on unionization. Pitt should recognize it is unwise to retread history on this issue.

What’s especially striking about Pitt’s last-ditch attempt to avoid a vote is how little faith the school seems to have in its own argument’s power to convince in the context of an election. If Pitt truly treats its graduate student workers well and a union organization would actually strain the relationship between the two, it would be a much smarter move to convince voters to decide against unionization in the election. Pitt’s choosing to relitigate a lost cause makes it look like the school is interested in little more than buying time.

The fact that the funding for the school’s strategic stakeout is likely coming directly from tuition money doesn’t help the school’s case, either. While a Pitt spokesperson refused to comment on the status of legal expenses from its anti-union venture, the update on Facebook from the grad student union organizers noted Pitt’s counsel in the newest case was the same law firm recruited in Penn State’s scrap with student unionizers.

It’s disheartening that the school is willing to pay legal fees in a seemingly redundant case but unwilling to provide its grad student workers with higher compensation. And a lack of transparency about its motives for relitigating the employee status makes it more obvious that grad students have good reason to want a union. While it’s unlikely Pitt’s case with the PLRB will lead to anything but a reaffirmation of its last decision, greater support for a union after the most recent controversy would only be natural — and it would be hard to blame them.