Black student organizations celebrate 50 years of pride, progress

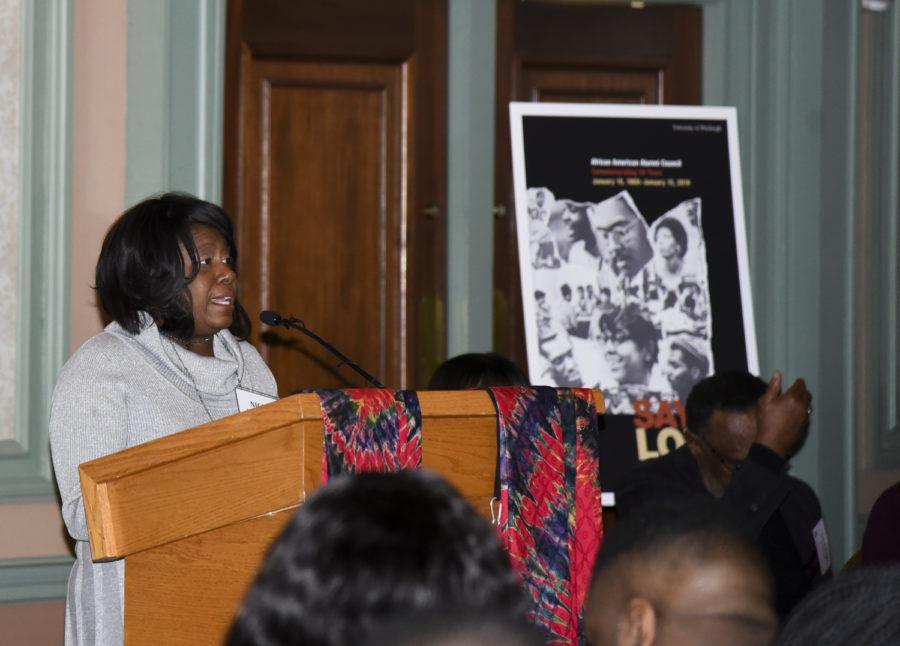

Knox Coulter | Staff Photographer

Nicole E. W. Parks, African American Alumni Council President, welcomes guests at “Say It Loud.”

January 16, 2019

During the height of the Civil Rights movement, in 1969, 40 members from Pitt’s newly minted Black Action Society shut themselves inside a Cathedral of Learning computer lab for seven hours to protest racial injustices on campus.

Pitt’s African American Alumni Council commemorated that effort yesterday by holding a 50th anniversary celebration called “Say It Loud,” a black power reference and the title of a memoir coming out in 2019 about the Pitt sit-in featuring testimony from first-hand witnesses, many of whom spoke at the event.

“Your presence today signifies your devotion and commitment to the achievements of people of color,” Council President Nicole Parks said, gesturing to the nearly 200 people in the Kurtzman room of the William Pitt Union.

That historic sit-in served as the primary impetus for then-Chancellor Wesley Posvar to create Pitt’s Africana Studies program and institute a quota system to accept more black students into the University.

“This group’s request of the University shouldn’t have been that controversial,” Chancellor Patrick Gallagher said. “That seed that was planted 50 years ago … it has deeper roots and has ushered in real change.”

Witnesses of the 1969 protest shared their experiences as protesters and ordinary black college students. Pitt alum Lorna Hubbard read out her University acceptance letter, which drew gasps from the audience.

“Despite our reservations, your record does offer sufficient hope for your success to justify our calculated risk,” the letter read. “Your mission presupposes that you will approach your task here with seriousness and maturity.”

Hubbard graduated with an degree in education in 1970. But even with her own success, she and her few black classmates, including former Pittsburgh education officer Curtiss Porter, lamented the lack of black students and black professors at Pitt in the late 1960s.

“We still weren’t seeing a black studies program … [or] black instructors, so we had to be strategically disruptive,” Porter said. “Black power was like a curse word back in those days.”

Hubbard was also concerned about safety when taking part in Civil Rights protests in 1969. The sit-in took place in the middle of the Civil Rights movement, one year after South Carolina police massacred black students who for protesting an all-white bowling alley and less than a year after King’s assassination shook America.

“We had no idea how long we would be in that computer center … we just went in knowing who we were and what we were owed,” Hubbard said. “We didn’t know if it would be peaceful.”

But after mere hours of sitting in the computer center, Posvar went in and negotiated with the students.

“There were no injuries, damages to property or police called,” Hubbard said. “It was very peaceful.”

Posvar signed a contract largely agreeing to the students’ demands. He hired more black faculty and introduced the University’s first Africana studies program. The first Africana studies program in the country was founded in 1969 at Cornell University after a similar student-led takeover of a campus building.

“With the takeover of the computer center we lived up to our name — the Black Action Society,” Porter said to applause from the audience.

The contract also ushered in a scholarship and recruitment program for black students that aimed to attract more students of color to the University. Among those recruited students was Linda Boyd, a teenager from Baltimore, who’d always hoped to attend a historically black college.

“I turned 17 and one week later my mom sent me off to Pittsburgh with two suitcases, a brown paper bag and white gloves,” Boyd said. “My lifelong dream was to go to Howard, but [Black Action Society’s] cause brought me here.”

The Black Action Society was the only campus organization devoted to the interests of black Pitt students in the late 1960s, but now there are more. Emily Arthur, a representative from Pitt’s African Student Organization, and Edenis Augustin, the president of Black Action Society, both spoke at the event to show their appreciation for the activists who made their existence possible.

“There are certain mindsets and values that only minorities can truly understand,” Arthur said to the audience. “Today on Pitt’s campus, black students are able to come together to better handle those cultural differences.”

Augustin pointed to a quote from a white student in a Pitt News article covering the sit-in to illustrate how much campus culture has changed. According to the article, the unnamed white male junior said the voices of the protesters wouldn’t be heard.

“You watch, nothing will come of this,” the student said.

Augustin said times have changed for black students at Pitt.

“I would love to see his face now that 50 years later the Black Action Society is not only still around, but a driving force for black activism in the Pittsburgh community,” Augustin said.

Gallagher echoed that statement in his address, calling the Black Action Society one of the most “vibrant groups” on campus, one that’s played an instrumental role in connecting Pitt to its black students.

When Hubbard first enrolled at the University, she said one statistic stuck out in her mind. Only 0.5 percent of students were black.

“Times are truly different now,” Hubbard said.

Pitt’s black undergraduate population now sits at 5 percent. Though white students still make up 70 percent of the undergraduate student body, this year’s incoming class of students was the most diverse in University history.

“This year we welcomed our most academically accomplished class in Pitt’s history and its most diverse,” Gallagher said. “The fact that those happened together is not an accident.”

As the black community at Pitt continues to grow, many members look forward to the progress that is to come.

“Say it loud across the nation, around the world. We are black and we are proud,” Parks said. “Proud members of this Pitt community.”