Opinion | Leave vaginas out of feminism

February 13, 2019

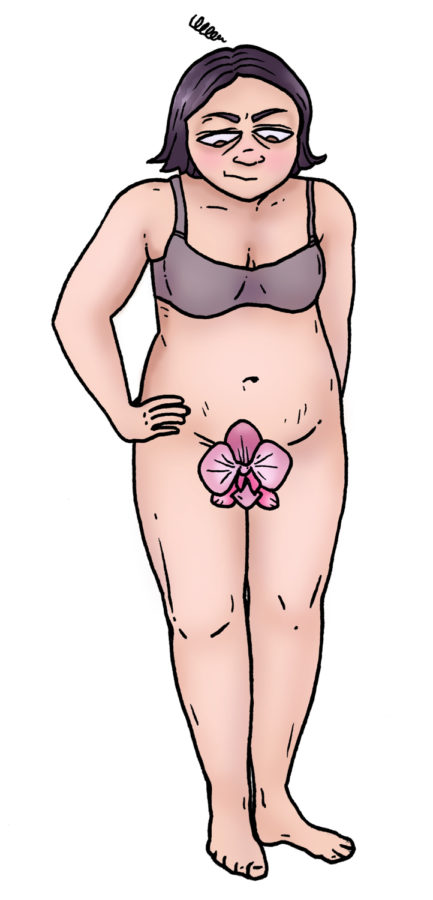

In order to march forward, it’s time to drop the vagina as a protest symbol.

The first annual Women’s March occurred on an unusually warm Saturday in January 2017. But the sunny weather and humid air didn’t stop hoards of women from showing up wearing pink “pussyhats.”

The hat is a simple knitted pattern with pink yarn, which folds upwards in the corners to resemble the ears of a pussycat. The official name is now being trademarked.

The vagina has become a symbol of resistance against female oppression, but the female gender is much more complicated than a body part. Sex, though it can be altered, is biological. But the Women’s March was never a movement focused on biology. Rather, its focus is gender discrimination and gender rights.

By definition, gender is a means of expression and is not fixed to biological sex. In other words, not all people who identify as female actually have a vagina. Feminism values inclusivity and intersectionality. If we really want to make feminism all-inclusive, then it’s time to step away from the pussyhats and vagina-oriented slogans.

Inclusivity, a trait central to feminism, was also a main mission for the founders of the Women’s March.

“Women’s March is a women-led movement providing intersectional education on a diverse range of issues and creating entry points for new grassroots activists and organizers to engage in their local communities through trainings, outreach programs and events,” according to the official website.

But the pussyhats, representing anatomy that some women do not have, don’t provide intersectional representation. And though the hats aren’t directly affiliated with the Women’s March itself, public figures affiliated with the march have shown their public support for the hats.

Cecile Richards, president of Planned Parenthood from 2010 to 2018, was inspired by the simple pink hat. She posted a video of herself knitting one for the march on her personal Instagram page.

The female creators of the pussyhat, Krista Suh and Jayna Zweiman, explain the personal meaning of the hat pattern on their website.

“[It] was chosen in part as a protest against vulgar comments Donald Trump made about the freedom he felt to grab women’s genitals, to destigmatize the word ‘pussy’ and transform it into one of empowerment and to highlight the design of the hat’s pussycat ears,” the women wrote.

Those who knit and sport the hats obviously mean well, but listening to women who express their discomfort is important. Vaginas promote a narrow view of feminism when applied to a movement as a whole.

The conflict over the vagina seems to have been pushed to the back burner, considering the other scandals the Women’s March has faced. Over the past few years, the march has been criticized for not being as inclusive as it claims to be. Organizers have been accused of anti-Semitic actions and racial discrimination.

Activists have made major efforts to increase inclusivity of the march. A founder of the march, Teresa Shook, made a public statement asking some of the co-founders to step down from their positions this past November.

“In opposition to our Unity Principles, they have allowed anti-Semitism, anti-LBGTQIA sentiment and hateful, racist rhetoric to become a part of the platform by their refusal to separate themselves from groups that espouse these racist, hateful beliefs,” Shook wrote in her Facebook post. “I call for the current co-chairs to step down and to let others lead who can restore faith in the movement and its original intent.”

Jade Lejeck, a 28-year-old trans woman from California, does not attend women’s movements. She was originally turned off by the pussyhat, as she felt that it signaled more trans discrimination within feminism ahead.

“I believe there’s a lot of inequality that has to do with genitals — that’s not something you can separate from the feminist movement,” Lejeck said in an interview with Mic. “But I feel like I’ve tried to get involved in feminism and there’s always been a blockade there for trans women.”

The founders and those who wear pussyhats mean well. But a change toward inclusivity starts with understanding feminist intersectionality and listening to the voices of those who feel excluded, including trans women and nonbinary people.

The International Women’s Development Agency published an article in 2017 highlighting the actions one must take to become an intersectional feminist ally. The second point examines the importance of people being able to “take the time to listen and make the space for others.”

The step emphasizes one’s willingness to listen to the opinions, requests and ideas of those who feel left behind in the feminist movement.

“Give them your full attention, and listen,” the article says. “Their stories may not make it into mainstream media often, but they’re there — sometimes it just takes a little digging.”

The creators of the pussyhat made a public statement on the lack of inclusivity in 2017.

“Some people have questioned whether the very name ‘pussyhats’ means our movement is saying only people with vaginas can be feminists. No way!” the website says. “Trans people and intersex people and people with any genital anatomy can be feminists and wear Pussyhats™. Feminists who wear Pussyhats™ fight transmisogyny and support ALL women.”

Despite the statement, many women are still uncomfortable with the protest symbol. The creators’ statement seems to indicate that people should conform to the idea that anatomy governs gender. But as feminists, we need to listen to the women who feel left out of the movement. If we want to show women without vaginas that they are just as much a part of the feminist movement as cisgender women, then it’s time to get more creative with protest symbols.

After all, the feminism is about empowering all women — not just those with a vagina.