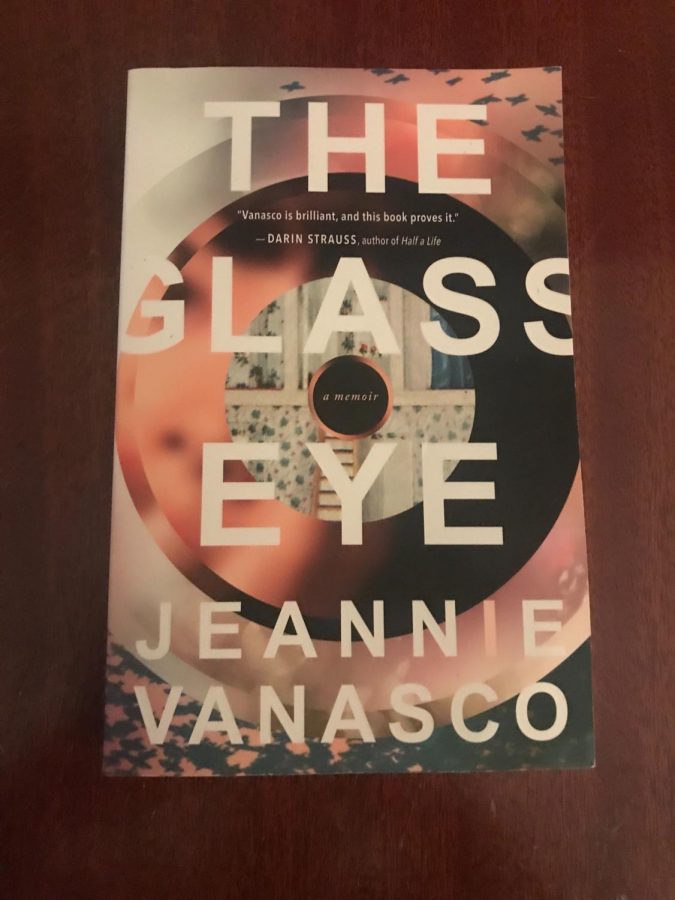

By the Book: “The Glass Eye” and writing about mental illness

By the Book is a biweekly blog about the real-life revelations that can come with class readings.

Warning: This edition of By the Book contains graphic content relating to sexual assault that some readers may not be comfortable with.

In one of our Essays & Memoirs class discussions a few weeks ago, I sat very still and did not say a word. The students around me animatedly discussed “The Glass Eye” with my professor. When we split into small groups, I let the words of my partners wash over me. I made agreeable sounds. I nodded rapidly. The entire time, I wondered, “Does everyone know that I am like Jeannie? That I, too, am crazy?”

I prefer “crazy” to “mentally ill.” The latter sounds so clinical, and I never feel clinical when I am in the trenches of my post-traumatic stress. I feel strange and untethered, like I might close my eyes and flicker from reality. Jeannie Vanasco is much the same in “The Glass Eye.” Her beloved father dies when she is only 18, and the deathbed promise she makes — to write a book about him — haunts her as devastating grief mutates into devastating mental illness. She hears a voice calling her name, obsesses for days and nights over poems and slices into the soles of her feet.

I walked out of the Cathedral and thought, for a fleeting moment, that I could feel cuts bleeding sluggishly into my socks. Nonsensical — and yet as I drove home, my foot on the gas pedal, I intermittently wondered whether there would be puddles of blood staring back at me when I removed my boots.

My boyfriend knocked me unconscious with a soccer trophy and raped me when I was 15, something I’ve written about for The Pitt News before. It’s an experience that is to me as Vanasco losing her father is to her — the event through which I will always conceptualize suffering. Everything I live through feels, somehow, connected to being raped — if I sit down and try to write a poem about a flower, it will turn toward the plucking of petals, something delicate destroyed by cruel and hungry hands. Which is to say: rape.

Vanesco, who believes that everything from the “i” in her name to her father’s glass eye is connected, suffers from the same plight. We both still reverberate from events beyond our control. In the fallout, we force together puzzle pieces that are not even from the same box, somedays aware of our own delusions, and others not.

I examined the soles of my feet under the flickering stove light. Calloused and uncut. “You are being crazy,” I said aloud to myself. Then I said it twice more for good measure, because three is my safe-safe-safe number.

Vanasco finished college with binders of obsessively categorized writing and a suicide attempt under her belt. She went on to write in some of the most popular nonfiction magazines in America, all the while working toward a poetry and nonfiction MFA. Still trying to find the right angle for her father’s book. Still trying to escape the agony of mental illness.

I’ve tended my MFA aspirations secretly, treating them like a small, precious plant which I hide from guests. I’m afraid that I cannot find the balance higher education demands of mentally ill people — to be honest, but not so honest that our risk outweighs our reward.

Every college student with a mental illness knows that the information they disclose to University employees can be used against them. A casual “I’m gonna die” from a student with documented mental health issues might guarantee a ‘wellness check,’ which is a nice way of saying a police escort to the deck of Western Psych.

Writing students, in particular, walk a fine tightrope. We are expected to recount our trauma honestly, wade through it to produce art, but not so much that the art we produce is traumatic. In an MFA workshop, one of Vanasco’s peers told her “The mental illness stuff … is the most interesting. There should definitely be more scenes of you losing it.” Her professor told her afterwards that the ending must provide assurance to the reader that though she hasn’t been fine (mental illness stuff), she is fine by the end (no longer losing it).

I have Title IX protections because my ex-boyfriend attends Pitt. Each semester, the office sends a formal email to my professors. The jargon serves as both shield and brand — I am crazy, but you cannot be mad at me for it. I might start crying in the middle of class, but you can do nothing but stiffly send me into the hall for a drink of water. I love my protections. I hate my protections.

Here lies the problem — if I get my MFA halfway across the country, I will have no legal reason to need Title IX protections. Vanasco, 10 years after her father’s death, technically had no reason to hospitalize herself with grief that felt only hours old. Both of our mental illnesses, which stem from two traumatic events, should have expiration dates. Higher education wants mental illness to have an expiration date — we must end our memoirs in recovery.

Vanasco’s meticulous organization meant three binders. One for her father, called ‘Dad,’ one for her mother, called ‘Mom,’ and one for herself, called ‘Mental Illness.’ That’s how intrinsic being sick is to her identity — one cannot exist without the other.

(I think, if I were to create binders, I would have only one, called ‘Rape.’ What else is there?)

“The Glass Eye” does not end with some symbolic scattering of ashes, nor a reassurance of recovery. There is no easy answer for Vanasco. I still sat in class, holding a published and acclaimed copy of her story. Someone might still sit in class and eventually hold my memoir, which might end with my promise that while I will not create cuts on the soles of my feet, I might always check for their phantom existence.

I am trying to be honest. I am trying to avoid causing concern. I am trying to do Vanasco’s story justice.

Have I done it? Have I done it? Have I done it?