African American Alumni Council buries time capsule for Black History Month

The African American Alumni Council celebrated the burying of numerous artifacts and archives in the form of books, essays and files from as early as 1968 in the first time capsule buried at the University since 1999.

February 28, 2020

Future generations of African Americans will unveil a carefully cultivated box of University history — but not until 50 years from now.

The African American Alumni Council gathered in front of about 20 people in the Connolly Ballroom in Alumni Hall Thursday to bury a time capsule containing numerous artifacts from the legacies of African-American individuals at Pitt.

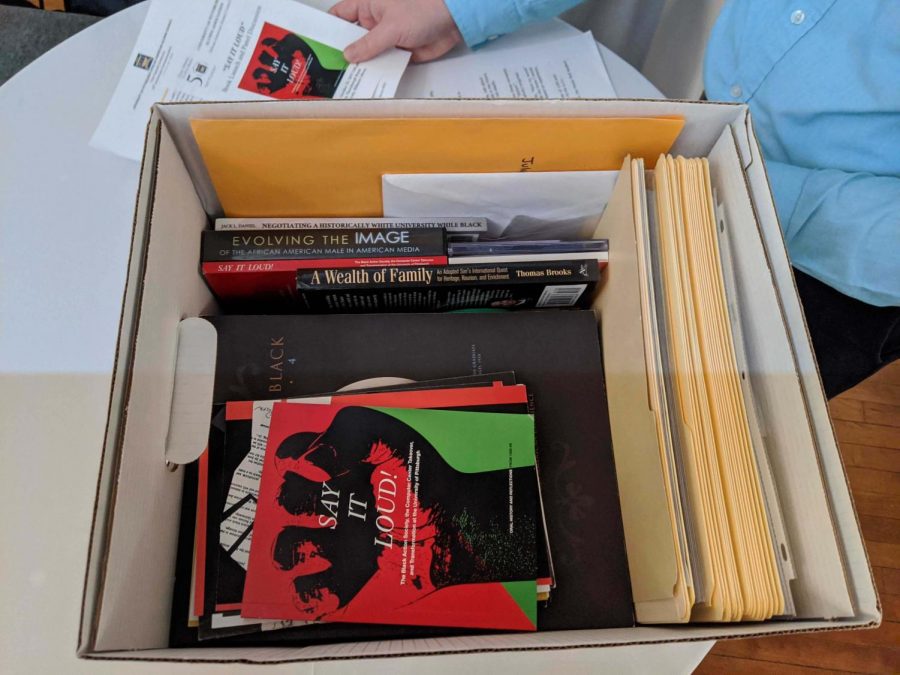

These artifacts include books, essays and files spanning from 1968 to present day, to be “buried” in a storage facility until the capsule is opened in 50 years. It will be the first time a capsule has been buried at the University since the Pitt Program Council time capsule was buried next to the Panther statue in 2000.

Macharia McCoy, a member of the Wisdom Seekers — a Pittsburgh-based group that discusses African history — and a former griot, or West African poet and storyteller, began the ceremony with a unifying demonstration in which attendees formed a human circuit, clasping their hands together. McCoy stood in the center of the circle watering a plant as a libation — or ritual offering to a spirit — each time the crowd expressed gratitude to their ancestors.

Instead of “Amen,” the crowd chanted “Ashe” at the conclusion of every utterance.

Afterward, Latara Jones of the National AAAC Board mediated a discussion on racial injustice issues on campus and in the surrounding community. The four panelists were Curtiss E. Porter, chancellor emeritus of Penn State Greater Allegheny, Kellie Ware-Seabron, Pittsburgh NAACP executive director, Jenea Lyles, president of Pitt Black Action Society, and Pitt Black Action Society member Aba Asantewaa Ofosuhene.

The time capsule contained books documenting the adversities and experiences of African-American people at Pitt, such as “Negotiating a Historically White University While Black,” by Jack L. Daniel and “Say It Loud!: The Black Action Society, the Computer Center Takeover, and Transformation at the University of Pittsburgh,” an oral history written by people with first-hand experiences of the events. Many of the capsule’s artifacts were contributed by members of the council.

Valerie Njie, president-elect of the Pitt Alumni Association, contributed an essay to the time capsule. She was one of the 50 African-American students admitted to Pitt — which was entirely white at the time — in 1968. Njie said she remembered the sense of community and empowerment throughout the African-American student body in her undergraduate years at Pitt.

“I think it’s very important to have those documents,” Njie said. “When I came here I was the first person in my family to ever go to college, and [Porter] was my first black teacher. Those individuals were the ones who pushed us and made us realize — not just in the classroom — what we had a right to take part in.”

Lyles spoke about student involvement on campus today, and described the struggles involved in tackling race-related issues.

“For us as students, it’s hard for us to see what is going on outside of campus,” Lyles said. “We’re very wrapped up in our studies, work and extracurriculars. If we have more conversations with those in the community, we could become more adaptive.”

Porter, a founding member of the Pitt Black Action Society, said the time capsule is largely representative of the transition between the initial integration of black Americans into white academica.

“It is difficult for students today to see themselves beyond their situation as students,” Porter said. “Back then, we saw our strength as members of the black community — not only on this campus, but in the city of Pittsburgh.”

Porter said the apparent lack in strength between students in the African-American community is due to the absence of a unified rights movement in the City.

“There is not a sense of struggle in the community, and there is not a movement afoot that people can see themselves in,” said Porter.

Ofosuhene, a senior majoring in health services, said she believes there is still room for improvement on Pitt’s campus.

“We face isolation and hardships as students at a predominantly white university,” said Ofosuhene. “There has not been enough of an increase of black students admitted to Pitt — the number has stayed at a steady 5%. We really want to see more students like us on campus.”

The panelists all expressed a similar sentiment that African Americans have long faced adversity in American society, but student organizations like Black Action Society are determined to create a safe space for students of color.

“My hope is that when people open the time capsule in 50 years, they will think that our concerns now were quaint, even silly,” said Porter. “When they open the box, what they see will be interesting and historical, yet irrelevant.”