Blog | So you’ve noticed my tic

March 18, 2020

At five years old, I scratched the palms of my hands until I had half-dollar-sized scabs and only breathed out of the corners of my mouth.

When I was seven, I either jumped or flexed my knees every three steps I walked, everywhere, all the time. I later discovered I have anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. But still, I’ve gone my whole life developing and losing different nervous tics and ritualistic behaviors that make people stare, make them ask questions, make me feel unnatural — and make me want to write about it.

Being insecure about my tics can cause blindness to tics of others — like I’m the only one — but when I witness someone else show the slightest sign of ticcing I feel my stomach flutter with a sort of affinity. However, college has been a different story, especially with this year being so stressful and nerve-racking. I’ve not only noticed countless more people with nervous tics and habits — I’ve come to accept how completely normal it is.

WebMD classifies tics as either simple or complex. Simple motor tics may include movements such as eye-blinking, nose-twitching, head-jerking or shoulder-shrugging. Complex motor tics consist of a series of movements performed in the same order.

I’ve had both simple and complex tics throughout my life. But my nervous tics seemed to settle in my face as I became older, as my older brother Nathan’s did. Both of us now seem to be prone to excessively blinking and scrunching up our faces in some way — a simple tic.

I couldn’t count the total of nervous tics that I’ve had and lost throughout my lifetime, but I’d estimate it’s in the teens — some very minor and non-noticeable, some utterly humiliating and even injury-inflicting. They’ve always made me feel out of place — why couldn’t I just stop? It seemed impossible, as defeating one tic inevitably led to the beginning of another.

Although tic disorders usually start in childhood — around 25% of children experience tics — all ages can experience tics, and they are more common among men compared to women. Many cases of tics are temporary and resolve within a year. However, some people, like me, develop a chronic disorder that affects about 1% of people who experience tics.

People who continue to experience symptoms beyond age 18 are less likely to see their symptoms resolved, and I’ve come to realize that I’m one of those people who — even after overcoming a tic — will undoubtedly develop another.

Although tics appear to be controlled in a sense, they’re often classified not as involuntary movements but as “unvoluntary” movements, meaning they are able to be suppressed for a time, but eventually need to be performed. The suppression results in discomfort that grows until it is relieved by performing the tic. In other words, the tic satisfies a sensation and suppressing it can affect the ability to focus. Suppression also causes the tic to be more severe when it’s finally released.

When I was younger, the only explanation I could provide for my insistence on performing certain rituals, behaviors, tics, twitches or habits was that I simply needed to — my mind and body felt compelled to, forced — and if I didn’t, if I suppressed it, I felt frustrated, uncomfortable, incomplete.

My excessive blinking began in middle school when I allowed my nerves and urge to tic develop into something relatively unnoticeable — but people still asked me why I blinked along to the beats of songs or why I was blinking 50 times in a row. Eventually instead of blinking a shit ton, I started blinking less but much harder — or scrunching, otherwise known as facial tic disorder — and it stuck.

Symptoms vary greatly among people with tic disorders, ranging from barely observable tics to severe and incapacitating symptoms. The short-lasting sudden movements occur suddenly during what is otherwise normal behavior and are often repetitive, with numerous successive occurrences of the same action — and I rarely realized I did it until people pointed it out.

Teachers would stop class to ask me if I was “all right,” groups of people would watch silently as I had a blinking fit then laugh and say, “What was that?” I’d respond that it’s just a thing I do when I’m nervous, ultimately making me more nervous.

Most people with tics are not nervous or struggling with anxiety. In fact, they’re often Type A personalities — people who are leaders or get things done. In some cases, they can be people who exhibit some kind of obsessive-compulsive behavior. Many also have parents or someone else in their family background who had tics.

My entire life I’d been Type A. An outstanding student, heavily involved in school and the community, well-behaved and well-liked — but my tics showed my deficiencies. They revealed a part of me I didn’t like — or could prevent — exposing.

Over a few years, the awareness of my tic had retreated to the back of my mind because of its consistency and my temporary consistency with life — but the change of coming to college and the sudden inconsistency of life made me more than aware — it made me tic like crazy. I believe my persistence in being successful stems from my OCD, causing the pressures of failure to wreak havoc on my associated anxiety and tics.

Since fatigue, anxiety and other stressful or emotional events often worsen symptoms in people with tic disorders, and college is a storm of emotion, my tic worsened, naturally, and my face moved uncontrollably sometimes. I’d have to cover my face to endure blinking fits without estranged looks. Simply, I felt trapped — unable to stop and unable to explain.

However, in the midst of my frustration, I also saw an influx of other people’s tics and habits arising as well. I felt odd watching strangers, waiting for them to snap their head a certain way or move their face uncontrollably or rub their hands together excessively. They make me feel a gratuitous bond, not just to them, but to myself — I wonder how many people watch me the same way.

Considering roughly three to eight people out of 1,000 are diagnosed to suffer from nervous tics, and neither my brother nor I have been diagnosed, I’d guess many other people haven’t either. This can be due to lack of severity necessary for diagnosis or late development of the tic, but either way, a diagnosis isn’t needed to notice the prevalence and normalcy of tics.

Typically, tics and twitches are not due to serious underlying mental or physical issues. Even if they are, they don’t dictate the severity of the disorder or the stability of the sufferer. To put it simply, performing tics satisfies a subconscious urge, and some urges are stronger or more frequent than others, but the tic is never within the discretion of the sufferer.

One night the topic came up during conversations and my friends naturally acknowledged the fact I had a nervous tic and just kept discussing — in front of me. I was completely taken aback at how normal they saw it, not as something abnormal, just something about me — it was liberating. My friend said he thought it was just a “cute” thing I do — phrasing that slightly offended, slightly flattered me. It was strange for something that’s vexed me to be positive or make me feel unique or even cute.

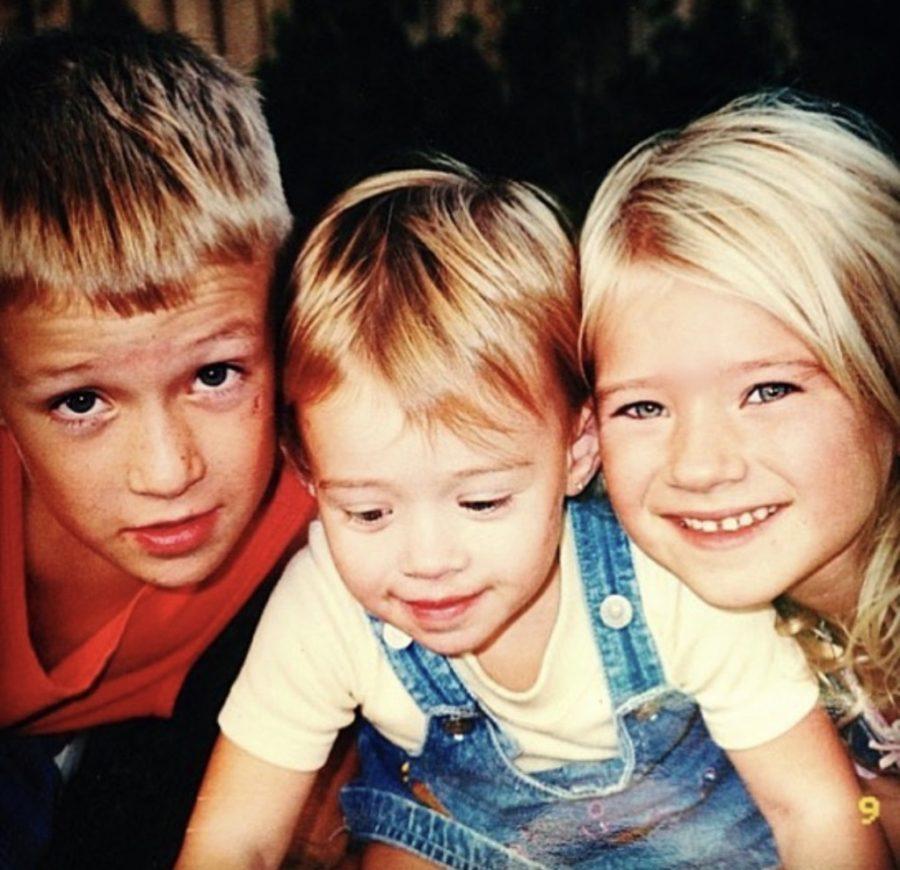

My mother now finds a strange pleasure in watching me and my brother together, waiting for moments when our faces scrunch at the same time and smiling saying she “loves it.” I want to say I hate it, but I’d be lying. Although uncanny, I couldn’t hate something I share almost completely with my brother. I couldn’t hate something that will truly never go away. I can’t hate something that is a part of me.

Sometimes I catch myself in a ticcing spell, an uncontrollable spurt of blinking, scrunching, snarling facial movements. I’ll look around to see if someone saw me, if they wondered what was wrong with me, if they saw it as something normal or cute, or if it made them feel a little less abnormal too. I still get insecure — after 15 years of tics I haven’t fully accepted the reality that I will most likely have them forever — that no matter how my life changes, my tics will change with me.

Having nervous tics hasn’t always made me feel normal, especially since it stems from relentless childhood OCD and anxiety — but I’ve come to realize those are common as well. A tic is kind of like a scar, a reminder of what I’ve dealt with — it’s struggling, healing and perseverance — in a single blink.