Former athletes push for change within Pitt Athletics

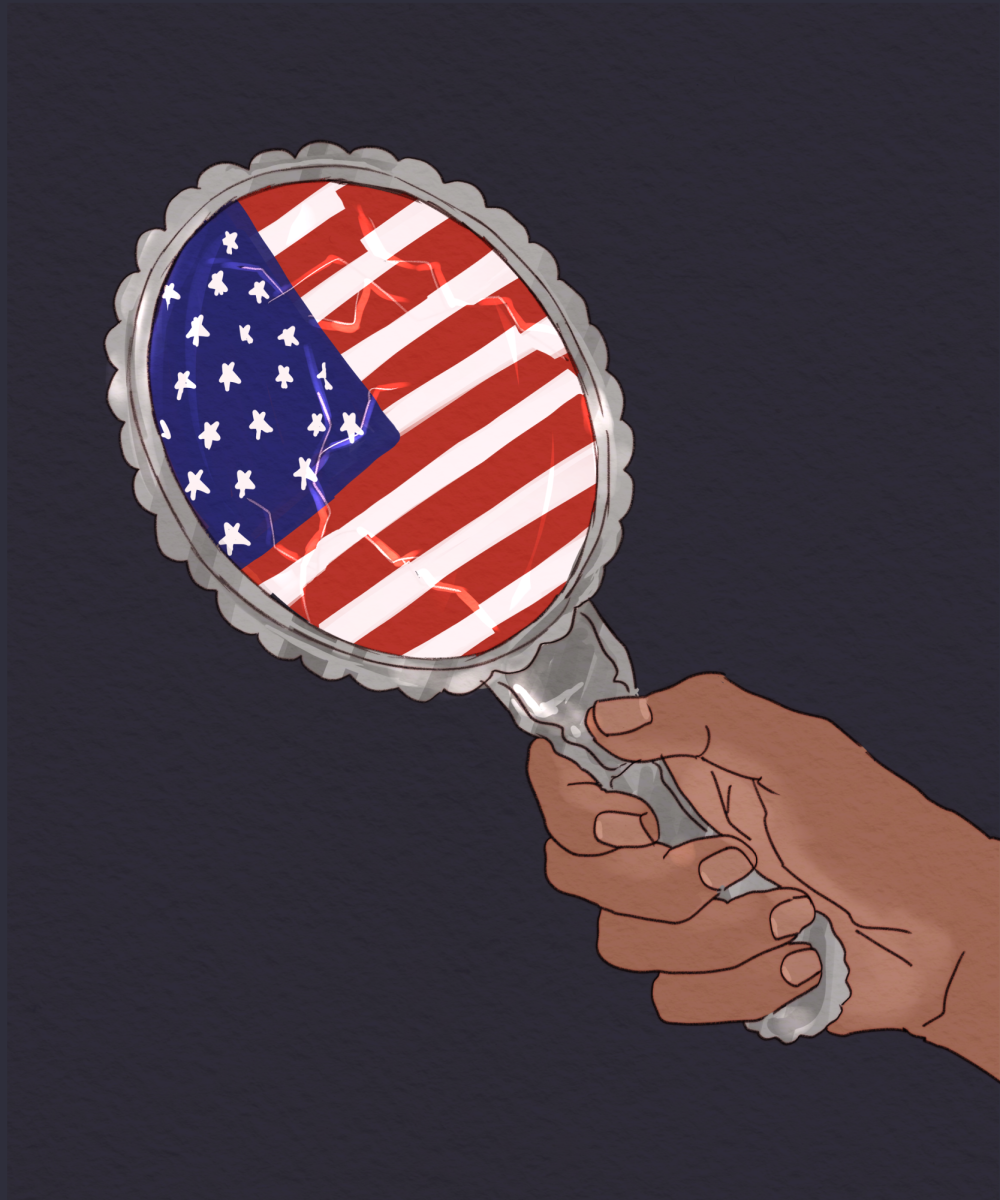

Courtesy of Jordan Fields and TPN File Photo

Former Panthers Jordan Fields (left) and Ian Troost (right) lead the push for change within Pitt Athletics following the death of George Floyd.

June 19, 2020

As people across the world seek justice and reform after the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, many student-athletes are demanding change at their universities. Former Panthers Jordan Fields and Ian Troost have joined together to spearhead an attempt to hold the University accountable and effect change.

Troost, a 2018 Pitt graduate, made headlines across the country as one of the few college athletes who chose to kneel during the national anthem in 2017, following Colin Kaepernick’s lead.

Fields, who graduated from Pitt in April, excelled at long and triple jump as a Panther. She became heavily involved in student organizations off the field, being appointed to positions with Student Government Board, the Panther Leadership Council, and Department of Athletic’s Pitt Script for Life Diversity and Inclusion Subcommittee. She also served as the president of Mu Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., during her senior year.

Both vocal on social media about the NCAA and Pitt Athletics’ delayed responses to George Floyd’s death, the two started working together a few weeks ago, after Troost defended Fields’ letter to the NCAA urging acknowledgement of recent events.

“We were like we should definitely connect at some point and figure out what we can do to help out kids at Pitt right now,” Fields said. “We know that they are probably not happy with what’s going on and the University hadn’t released anything.”

Troost, who grew up in Portsmouth, N.H., said his community that he grew up in was fairly homogeneous. Primarily a soccer player, he first attended Westminster College in Utah, where he started to learn about institutionalized racism. He transferred to Pitt for his junior year, where he took over the role of Roc, the school’s mascot. Troost earned a walk-on spot the next year as a kicker on the football team.

He made the decision to kneel before Pitt’s home matchup against Rice, with planning help from Pitt Athletics’ Life Skills team. At the time, head coach Pat Narduzzi released a statement showing his support for Troost’s decision. But Troost said Pitt Athletic Director Heather Lyke and Football Chief Operating Officer Christian Spears met with him afterwards, where he said they initially praised his actions, before chiding him when he said he planned to continue the protest.

“The conversation took a pretty sharp turn to me not having any idea of what I was talking about, being selfish as well as the fact that I didn’t understand the full implications of what I was doing in terms of cost to the University,” Troost said. “It was very much prioritizing the possible lost revenue over what the actual protests stood for and the conversations that need to be had that are to me way more important.”

Pitt Athletics spokesperson E.J. Borghetti declined to comment on the meeting.

Fields also praised Pitt Life Skills as one of the best such departments in the country, fulfilling their commitment to their student athletes. Although she was heavily involved in student activism in high school, she mostly focused on her sport during her first two years at Pitt. After deciding she wanted to make a larger impact, she began joining extracurricular organizations during her junior year.

Among her biggest accomplishments on SGB’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee was when Fields and two other Black student leaders sent Pitt officials a letter demanding now rising senior Ethan Kozak’s expulsion after racist messages he sent last summer were publicized. Fields and several other students met with Vice Provost and Dean of Students Kenyon Bonner and other administrators about strengthening the Student Code of Conduct.

“That was big because my senior year there were incidents where racially insensitive language was being used in dorms and on-campus, so that was a big win,” Fields said.

Following Floyd’s death and the ensuing global uproar, Troost and Fields have spoken with current and former Pitt athletes to determine the next steps the University can take to support black student-athletes. It culminated in an open letter sent last week to Pitt Athletics with several demands.

In the letter, Troost acknowledged his responsibility as a white ally “to amplify the voices of my Black peers,” before Fields laid out a series of demands to improve the experience of current Black student athletes. The demands included the creation of a formal committee of athletes to hold the school accountable to ensure Black student-athletes concerns are met, mandatory anti-racism and anti-bias training, the hiring of a black mental health counselor, a specific administrator tasked with dealing with whistleblower complaints, the reinstatement of collaborative events with local groups to celebrate Black athletes and the end to all ties with donors who have exhibited racist behavior.

Pitt said in response that the letter reflects the “true spirit” of the University, and it looks forward to “more communication and working together on these crucial issues” with student-athletes, coaches, staff and the University community.

While Troost and Fields concede it will not be quick to create change, they said they’d like Pitt to come up with a specific plan for how they will address these concerns.

“Jordan and I and everyone we’ve been talking to see this avenue, this pathway, for Pitt Athletics to be the best possible athletic department in the country,” Troost said. “We already have one side in place with the best life skills program, how can we set other programs up and other plans of action to just make Pitt Athletics that much more accessible, that much more inclusive for all student athletes.”

Fields said mental health was a particularly important issue, and attended the Black Student Athlete Summit to discuss the issue.

Pitt Athletics currently employs two clinical counselors, both white, which Fields said she’s heard positive feedback about from teammates. While Fields didn’t utilize mental health counselors during her time at Pitt, she said adding a Black counselor would make Black athletes more likely to come forward about topics regarding race.

“I would’ve felt more comfortable going to a Black man or woman when talking about microaggressions that I experienced on campus, or certain arguments I’d gotten into or stress that I was feeling simply because of the color of my skin,” Fields said.

Troost, who has since moved back to Portsmouth, now coaches the JV girls soccer team at his former high school. He said he’s made a direct effort to allow his players a chance to have these important discussions within the team.

“I learned a lot about how to try to answer empathetically and I tried to learn how to not necessarily shut down a conversation because it was outside of what we should’ve been talking about because it’s practice time or soccer time,” Troost said. “I always tried to make sure that we had ten minutes before or after practice to have those conversations.