‘The gift that keeps on taking’: Virtual town hall discusses relationship between capitalism, inequity

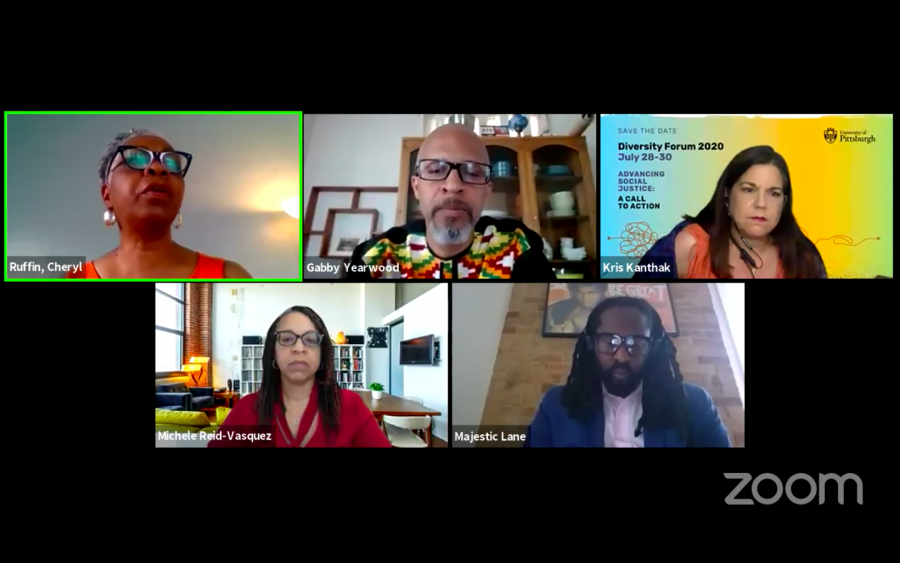

Cheryl Ruffin hosted the Office of Diversity and Inclusion’s Wednesday town hall.

July 8, 2020

American economic and political systems were never meant to be equitable, Gabby Yearwood said, instead only to benefit their makers and the people that look like them.

“The system is designed, and has been designed intentionally, to create inequity and protect those who are the most elite,” Yearwood, a lecturer and director of undergraduate studies in the anthropology department, said.

Yearwood and other members of the Pitt community spoke at Wednesday’s “Toxic Recipe: The Historical Ingredients of American Inequity” virtual town hall presented by the Office of Diversity and Inclusion. This installment was part of the “This is Not Normal: Allyship and Advocacy in the age of COVID-19” town hall series. Cheryl Ruffin, ODI’s institutional equity manager, moderated the event.

Majestic Lane, the City’s chief equity officer and a deputy chief of staff to Mayor Bill Peduto, said capitalism is a system that inherently has two outcomes — inequities for citizens of color and profit for the white majority.

Lane said capitalism is the “gift that keeps on taking,” since it “both inhibits growth for a group of people and it confers privilege and benefit to a group of people.” This dual nature is often difficult for people on the receiving end of privilege to understand, he said, since they believe that if the system is able to confer them privilege, it is able to do so equally for everyone else.

Lane added that this way of thinking creates an endless cycle of Americans using the “silver-bullet model,” where people think of inequality in terms of touchpoints — individual events such as drug crises and educational disparities — that a government can funnel money toward in order to solve the problem. But he said this method only scratches the surface, and ignores the deeper systems that created the issues in the first place.

“From looking at the wealth gap, you can’t separate the fact that the wealth gap has been compounded over hundreds of years,” Lane said. “But if you try to deal with it as a one-time thing, it’ll always fail. And when it fails, people will say you can’t solve it. The reason they say you can’t solve it is because we looked at it incorrectly.”

Lane added that it’s impossible to separate the problem from the system because there is no single solution that can stop the underlying system of oppression.

Capitalism rewards the silver-bullet model, Yearwood said, because the underlying systems of racism in America are directly tied to our commitment to capitalism.

“Capitalism works off of thinking of one’s own self at the expense of others,” Yearwood said. “We can’t talk about racism without talking about capitalism and materialism and the value that we put on people that accumulate wealth more than others.”

Michele Reid-Vazquez, an associate professor of Africana Studies, echoed Yearwood’s remarks and said racism is an economic issue relating to the disproportionate flow of resources.

“It can’t be this uneven flow of resources, it does have to encompass large populations and they have to be administered with transparency and accountability,” Reid-Vazquez said. “You can’t just look at a community and decide ‘they don’t need this’ without having those conversations, without having the kind of engagement to make it happen.”

The uneven distribution of resources has been especially apparent during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Yearwood said, with the COVID-19 mortality rate of Black people nearly triple that of whites. But statistics like these are nothing new, he said, because Black Americans “are in the populations that have always been hurt.”

“They’ve been living in a racist pandemic for 500 years. There’s no surprise that they are the most vulnerable in all of this,” Yearwood said. “The reason the United States is spiking and increasing is because people don’t care. People only care about themselves and their own choices.”

But Lane said the realities of the racial pandemic no longer surprise the public, since the systems have been designed to make them that way.

“It appears to be natural and normal, when in reality it is designed to produce the desired outcomes. It is designed to do exactly what it has been doing,” Lane said.

As an institution of higher education that is so integral in the broader community, Ruffin said, the University has the power to not only mobilize but also organize its students and staff to shift the systems of oppression toward a more equitable campus.

“I think it’s also having an opportunity to look at what our current, particularly in higher ed, our current policies and procedures where we find the stops in so many ways,” Ruffin said. “We are the Cathedral of Learning.”

The first step in creating an equitable environment for all people, Yearwood said, is abandoning one’s individual perspective for a more empathetic view of the community at large.

“You cannot love someone unless you recognize their humanity,” Yearwood said. “We have to think about one another. We have to think about others before we think about ourselves.”