Pandemic Panthers: Reliving Pitt’s 1918 national championship amid the Spanish flu

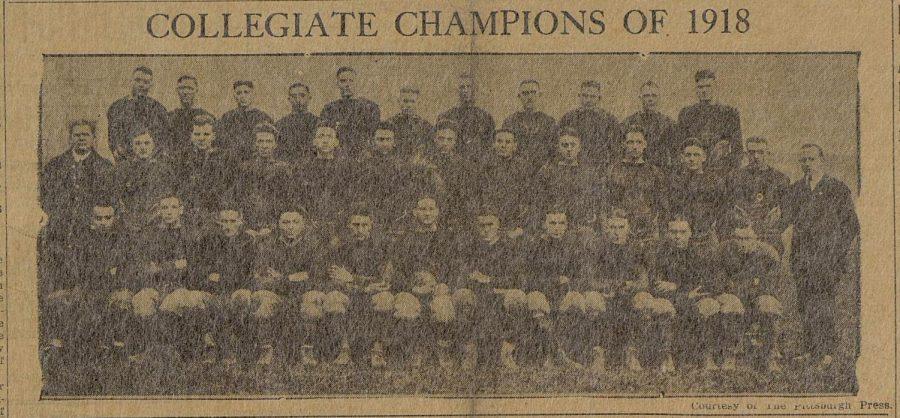

Pitt’s 1918 football team won the national championship amid the Spanish flu pandemic.

September 15, 2020

Even in an era where players didn’t wear helmets on the field, fans still had the sense to wear masks off of it. The last time a college football season occurred amid a pandemic, Pitt went on to win the national championship. That storyline has circulated for several weeks, but what actually happened during the 1918 season, when the Spanish flu ran rampant?

Legendary head coach Pop Warner led the Panthers from 1915 to 1923, claiming three national titles. Warner helped create the game as we know it today, innovating how offensive linemen block and creating the single and double wing formations — precursors to the modern day shotgun attack.

Warner did more than change how teams played the sport — he also changed how you couldn’t play it, exploiting loopholes that forced the creation of new penalties and changes to the rulebook.

The Panther offense, powered by three All-American running backs — Tom Davies, Katy Easterday and Skip Gougler — as well as fullback and team captain George McLaren, led the championship run. Davies ranks No. 7 in all-purpose yards (3,931) and No. 19 in points scored (181) in Pitt football history, handling kicking duties, too. McLaren led the team in scoring that year with six touchdowns, adding on two extra points. Both McLaren and Davies would later be enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in Atlanta.

Keep in mind, though, the college football landscape looked nothing like it does today. Only one bowl game existed at the time — the Tournament East-West Football Game — and it had been played just three times. It would become known as the Rose Bowl in 1923. Independent teams such as Harvard, Princeton and Yale dominated. Today’s perennial power Alabama wouldn’t win its first championship until 1925. The Heisman Trophy wouldn’t be awarded until 1935 and the AP Poll would come into existence a year after.

Davies, a true Swiss army knife, led the 1918 team in passing, rushing and receiving yards, and he gained less than 150 yards in two of those categories.

Interception statistics were based on the number of yards they were returned for, not the number caught. William Harrington, who played on both offense and defense, led the team in that category with 7 yards. On offense, Harrington played at the end position, the general term for both tight ends and wide receivers before the forward pass became common.

Schools didn’t play formal schedules in those days, and most teams played about seven in a season that went from late September to Thanksgiving. The 1918 season was postponed for many teams by a month due to the Spanish flu, whose deadly second wave hit the East Coast that fall.

Sports leagues carried out in impromptu fashion much like this year, with teams cancelling games as needed, while others played on. The Texas Longhorns managed to sneak in nine games by playing through the pandemic — the Panthers only played five.

Pitt kicked off the season with a Nov. 9 game against the Washington and Jefferson Presidents. The Panthers shared Forbes Field with the Pirates — Pitt Stadium wouldn’t open until 1925 — and wouldn’t leave the City until after Thanksgiving for their final game. It had been 11 months since the Panthers played, but that didn’t slow them down, roaring to a 34-0 victory, They blew out the Penn Quakers 37-0 a week later, their largest margin of victory of the season.

The Panthers faced the Georgia Tech Golden Tornado next, who’d be known as either the Tornadoes and Yellow Jackets for the next decade. Fans anticipated the matchup against the reigning champion, in part because Warner had turned down an invitation from Georgia Tech head coach John Heisman to play for the title in 1917. The 1918 game raised money for war charities.

The Panthers would leave no doubts that they were the better team that year, throttling Heisman’s team 32-0. Davies accounted for three touchdowns, throwing one to Easterday before returning a punt and rushing for another, the only points Georgia Tech allowed that season.

Their next game came just five days later on Thanksgiving, in a rivalry match against Penn State. The Nittany Lions scored six points, the first points the Panthers surrendered all season, but not nearly enough to win — Pitt dispatched them with ease, winning 28-6.

The Panthers then traveled to Cleveland for their lone road game of the season, playing on just two days of rest. They faced a football team fielded by the Cleveland Naval Reserves, cobbled together by players from other colleges who had wanted to join the war effort. Warner and many of the reporters covering the game claimed that it was rigged because of the questionable timekeeping methods used by the referees.

What followed would become college football folklore — the referees asserted that the timekeeper’s watch was broken, using this as an excuse to call an end to the first half as the Panthers drove downfield. In the second half, Cleveland scored to go up 10-9, and the referees immediately called the game, giving Warner his first loss in 33 games with Pitt.

Warner refused to accept the loss, and Pitt was retroactively named the national champion by the Helms, Houlgate and National Championship Foundation (NCF) committees in 1936 when the selection committees, who elect a champion in the absence of an actual title game, were formed. Billingsley and the NCF (as a co-champion) recognized the University of Michigan in honor of their 5-0 season.

Pitt’s 1918 season is a window in time, a fascinating glimpse into the early days of a beloved sport. And one that’s especially poignant because of its relevance to the pandemic season 2020 has become. Maybe Pitt can finish on top like the Panthers of 102 years ago.